|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

9 Science Cannot Write a User Manual for the Human Being

The Grand Narrative of Science is defined by its Central Dogma, enunciated concisely by biologist H. Allen Orr, “The universe, including our own existence, can be explained by the interactions of little bits of matter.”[1] In the same vein, Francis Crick, the co-discoverer of the double-helix

structure of DNA, preaches that “‘you,’ your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. You’re nothing but a pack of neurons.”[2] Psychologist Joshua Greene and neurobiologist Jonathan Cohen expound that “every decision is a thoroughly mechanical process, the outcome of which is completely determined by the results of prior mechanical processes. Every human action can be explained mechanically.”[3] Or said in up-to-date scientific terminology, “The human being is the manifestation of an extraordinarily complex neuro-network that emerged after millions of years of evolution.”

The Grand Narrative of Science denies responsibility for the action of any individual human being. “Any crime, however heinous, is in principle to be blamed on antecedent conditions acting through the accused’s physiology, heredity, and environment,” Richard Dawkins claims.[4] We humans cannot accept such a position “because mental constructs like blame and responsibility, indeed evil and good, are built into our brains by millennia of Darwinian evolution.”[5] In Dawkins’ view, a jury trial to determine guilt or innocence makes as much sense as a man beating his car with a tree branch because it refuses to run.

Human beings possess no agency, and thus, they are not users; instead, they are material objects used by nature and culture. In such a world whose fundamental constituents are quarks and leptons, the human being as understood by Plato and Aristotle is an alien, and nature is not a guide for human living. In addition, modern technology has caused nature to recede from everyday life. Literary critic Sven Birkerts likens digital cameras, cable TV, and the World Wide Web to a “soft and pliable mesh woven from invisible thread” that covers everything. “The so-called natural world,” he writes, “the place we used to live, which served us so long as the yardstick for all measurements can now only be perceived through scrim. Nature was then; this is now.”[6]

10 The Failure of the Grand Narrative of Science

By the mid-twentieth century, the Grand Narrative of Science was shown to be false through a straightforward argument, not an involuted, abstract one that only the most intelligent scientists and philosophers could grasp. Erwin Schrödinger pointed out that the human person is not a manifestation of an exceedingly complex neuro-network and cannot be explained by the interactions of tiny bits of matter. He asked us to consider a landscape painter. Suppose sunlight is reflected from a red apple into his eye. The sunlight passes through the lens of the eye and strikes the retina, a sheet of closely packed receptors — 4.5 million cones and 90 million rods. Activated by the incoming sunlight, chemical changes occur in the rods and cones, which are then translated into electrical impulses that travel along the optic nerve to the brain. Further electrical and chemical changes take place in the brain. This description is complete in terms of the physiology of seeing; however, the sensation red has not entered this scientific account of perception. The landscape painter experiences the red of the apple, not the various chemical and electrical changes necessary for seeing. Surprisingly, a detailed scientific understanding of the eye and the brain does not include the perception of color.[7]

Textbooks typically gloss over the profound difference between sense perception and its necessary physical components. With regard to vision, Francis Crick, the co-discoverer of the double-helix structure of DNA, confesses, “We really have no clear idea how we see anything. This fact is usually concealed from the students who take such courses [as the psychology, physiology, and cell biology of vision].”[8]

Physical-chemical changes in the brain are insufficient to explain sensory perceptions. Mechanical, chemical, and electrical changes are not perceptions, thoughts, desires, or emotions. The toolbox of physical science is limited to air pressure, chemical changes, electrical impulses in nerves, brain cell activity, and other measurable properties of matter. Materialism is mute about hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, and touching. Although science has made great strides in understanding brain physiology, we, nevertheless, our profoundly ignorant about the connection between brain physiology and the interior life, which is nonmaterial. For the outsider observer, say a neuroscientist, perceptions, emotions, and thoughts cannot be touched, smelled, tasted, heard, or seen, and thus are unobservable.

Human beings as well as the higher animals are not material beings, and thus they cannot owe their existence to the mindless evolution of matter. If our source is not matter, then it must be something nonmaterial, something transcendent, and in Western culture that is Divine Mind, or God. Historically, the denial of our origins and the insane goal of returning ourselves to the Garden of Eden brought about killing on an industrial scale and misery on a cosmic level, something never experienced by humanity before.

11 No Animal Can Grasp a Whole

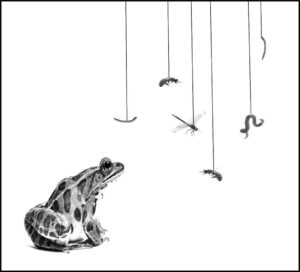

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inserted tiny electrodes into a living frog’s optic nerve to measure the electrical impulses traveling to the frog’s brain. Using this technique, the researchers formed a good picture of what the frog sees and how. They found that when a small object is brought into the frog’s field of vision and left immobile, the frog’s eye sends electrical impulses to the brain for a few minutes but then ceases to do so. After a short time, the object is no longer there as far as the frog is concerned. The reason for this disappearance is that the frog’s retina is designed to detect small moving objects. If a small object ceases to move in the frog’s field of vision, the retina cancels it out of the frog’s world. Furthermore, the retina’s circuitry computes the velocity and trajectory of a small moving object so that the frog can aim its tongue ahead of where the object actually is.

The researchers reported that “the frog does not seem to see or, at any rate, is not concerned with the detail of stationary parts of the world around him. He will starve to death surrounded by food if it is not moving. His choice of food is determined only by size and movement. He will leap to capture any object the size of an insect or worm, providing it moves like one. He can be fooled easily not only by a bit of dangled meat but by any small object.”[9] (See Figure 11.1.[10])

A frog cannot see a fly as such; it sees small moving objects. The MIT researchers also discovered nerve fibers that respond to the net dimming of light. These specialized fibers alert the frog to the danger of a nearby large moving object. In effect, the frog’s eye has only two categories: “my predator” and “my prey.”

Similarly, ethologist Jacob von Uexküll, among the first to document the remarkable specificity of animal perception, discovered that a jackdaw is unable to see a grasshopper that is not moving: “A jackdaw simply does not know the shape of a motionless grasshopper and is so constituted that it can only apprehend the moving form. That would explain why so many insects feign death. If their motionless form simply does not exist in the field of vision of their enemies, then by shamming death they drop out of that world with absolute certainty and cannot be found even though searched for.”[11]

The narrowness of animal perception can produce astounding results. Here are several of the hundreds of examples discovered by ethologists.

A deaf turkey hen will peck all her own chicks to death as soon as they are hatched. The distressed cheeping of the chicks is the only stimulus that inhibits the hen’s natural aggression in defense of the nest. The cheeping alone evokes a maternal reaction in the hen. Without the cheeping, a chick is judged by instinct to be an enemy and is attacked. A hen with normal hearing will attack a realistic stuffed chick if it emits no sound and is pulled toward the nest by a string. Conversely, she will respond maternally to a stuffed weasel (the turkey’s natural enemy) if it has a built-in speaker that produces the cheeping of a turkey chick.[12] Just as the frog cannot see a fly, the mother turkey cannot see its offspring!

Animal behavior is extraordinarily easy to misinterpret. For instance, a person observing a flock of jackdaws mobbing a cat that has captured one of their numbers might assume the birds had understood the situation and had chosen an appropriate course of action. Not so. Lorenz reports that on one occasion when returning home from a swim, he was suddenly attacked by the normally friendly flock of jackdaws that nested on the roof of his home. When Lorenz withdrew a black bathing suit from his pocket, the birds screeched their sharp, metallic mobbing call and attacked Lorenz’s hand to free the “captive bird.” The flapping, black bathing suit triggered the jackdaw’s mobbing instinct. Lorenz

remarks, “Of all the reactions which, in the jackdaw, concern the recognition of an enemy, only one is innate: any living being that carries a black thing, dangling, or fluttering, becomes the object of a furious onslaught.”[13] The jackdaws perceive black, they perceive flapping, but amazingly they cannot perceive bathing suit or even jackdaw. (See Figure 11.2.)

Primates, considered the most intelligent of animals, also do not perceive the what of things. Primatologist Wolfgang Kohler reports on the narrow perception of chimpanzees, “I tested them with some most primitive stuffed toys, on wooden frames, fastened on to a stand, and padded with straw sewn inside cloth covers, with black buttons for eyes. They were about forty centimeters in height and could perhaps be taken for caricatures of oxen and asses, though most drolly unnatural. It was totally impossible to get Sultan, who at that time could be led by the hand outside, near these small objects, which had so little real resemblance to any kind of animal. He went into paroxysms of terror, or threatened recklessly to bite my fingers, when I . . . tried to draw him towards the toy, as he struggled and strained backwards. One day I entered their room with one of these toys under my arm. Their reaction-times can be very short; in a moment a black cluster, consisting of the whole group of chimpanzees, hung suspended from the farthest corner of the wire-roofing, each individual trying to thrust the others aside and bury his head deep in among them.”[14]

How remarkable that the apes perceived the shape, size, color, and design of the stuffed toys but could not see what they were — harmless cloth and wood. Psychologist Patterson discovered the same thing while training her female gorilla: “Although Koko has never seen a real alligator, she is petrified of toothy stuffed or rubber facsimiles. . . . I have exploited Koko’s irrational fear of this reptile by placing toy alligators in parts of the trailer I don’t want her to touch.”[15]

The great discovery of ethology is that animals do not perceive what things really are; an animal’s perception is limited to a few key elements that cause it to act. Uexküll summarizes the scientific study of animal perception with a powerful metaphor: An animal’s world is not the world we see at all but more closely resembles “a small, poorly furnished room.”[16]

To picture the impoverished perceptual life of animals is extraordinarily difficult. We perceive the what and the why of things, substances and causes, not just black and flapping, but swimming suit and returning swimmer. Only extreme and rare pathology can cause a human being’s perceptual life to approximate that of an animal. Oliver Sacks, a neurologist, reports that a neurological patient of his picked out key features of a scene, “a striking brightness, a color, a shape . . . but in no case did he get the scene-as-a-whole. . . . He had no sense of a landscape . . .”[17]

Animals have no relationship to things beyond utility. The bloodhound’s sense of smell is acute enough to detect a person’s unique scent from a five-week-old fingerprint, but the hound uses its expert nose to track animals, never to delight in the fragrance of a rose. A barn owl can distinguish objects in light one hundred times dimmer than the light human beings need to see anything, but the owl uses its keen night vision to sight rodents, never to study the yearly motion of Venus. An animal perceives things only under the aspect of what is useful or harmful to itself and hence ignores virtually all of nature.

Of all the natural creatures, only human beings can get beyond utilitarian needs. A frog cannot see the iridescent, filigreed wing of a fly, nor can the fly see the frog’s glistening head and jet-black eyes. A ten-year-old boy seated on the bank of the pond can take in the frog and the fly, can see the puffy white clouds racing across the blue sky, and can feel the warm spring breeze. Without the presence of a human being, the scene does not exist.

Every animal is trapped within the narrow world of utilitarian desire, unaware of even its own beauty. The tiger does not know what a wonderful thing a tiger is; only a human person knows that. What characterizes human life in contrast to animal life is that a human person can get outside himself or herself through love.

If you want to experience the human way of life, go outside at night and look at the stars, or in summer, pick up a dandelion and look at it, or gaze into the eyes of the next person you see. Only a human person can fall in love with the other; only a human person is open to all existence. Who are we? We are lovers. Each person is, as it were, the eyes and ears of nature. Instead of inhabiting “a small, poorly furnished room,” each human person through love can be connected to all that is.

12 Nihilism Overcome

Albert Camus, a vigorous opponent of nihilism, yet a defender of the absurd, laments in his book The Myth of Sisyphus, “If I were a tree among trees, a cat among animals, this life would have meaning, or rather the problem would not arise, for I should belong to this world.”[18] At the conclusion of his book The First Three Minutes, physicist Steven Weinberg declares, “The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.”[19] The startling thing is that this sense of futility is not found in physics, nor does it necessarily follow from any observation of the universe. Most likely, the source of Camus’ and Weinberg’s estrangement is not in reason or in nature but in modern culture. We moderns do not feel a part of nature because our culture isolates us, and as a consequence creates in us an emotional pattern of feeling alone and not part of things. The estrangement expressed by Camus and Weinberg immediately resonates within us, not because of our knowledge of philosophy or physics, but because we share the same emotional pattern with them.

It does not take a Ph.D. in philosophy to see that if I succeed in disconnecting myself from everything, then life can only appear absurd. Disconnected from persons and things, it is impossible to complete the sentence “The point of my life is _____.” In isolation, my life is pointless.

Camus and Weinberg made the understandable error that “this world” is the same for all creatures. A tree and a cat each have a limited world. A tree draws in nutriments and water through its roots, takes in sunlight, and respires. The world of tree is extraordinarily small, in effect not extending beyond what touches it. As we saw, a frog’s or a jackdaw’s world is not the world a human being experiences, but more closely resembles “a small, poorly furnished room.”[20] No animal can perceive the what of things, much less the causes of things. Contrary to Camus and Weinberg the human being does have a privileged position in nature and possesses a unique “mission” beyond biological life.

Unlike animals, human beings can act contrary to their nature. Although nature fixes our purpose — to be connected to all that is — because we are free, we can choose not to achieve our end. Either through ignorance, cultural habituation, or personal choice, we can limit our world to a “small, poorly furnished room.” Karl Marx pointed out years ago how marketplace values restrict a person to seeing merely an object’s utility: “The dealer in minerals sees only the commercial value but not the beauty and the unique nature of the mineral.”[21] Such a dealer of gems has trained himself to have frog vision.

In his book The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald imagined what the first Dutch sailors to the New World saw: “For a transitory enchanted moment, man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”[22]

13 We Are Spiritual Beings

Of all the natural creatures, only human beings can grasp a whole. The study of animal perception re-discovered the spiritual nature of Homo sapiens — the capacity to be connected to all that is, a fundamental principle of every wisdom tradition.

Ancient Greek: “The human soul is, fundamentally, everything that is.”[23]

Hindu: “Thou are that.”[24]

Christian: “Every other being takes only a limited part of being whereas the spiritual soul is capable of grasping the whole of being.”[25]

Jewish: “At opposite poles, both man and God encompass within their being the entire cosmos. What exists seminally in God unfolds and develops in man.”[26]

Islamic: “Who knows his soul knows his Lord.”[27]

Chinese: “He who cultivates the Tao is one with the Tao.”[28]

Native American: “To walk the path of beauty, you must connect to all things, take them seriously, with reverence.”[29]

Main Image: A detail of Creation, Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo. Public domain.

Part III: Connecting

[1] H. Allen Orr, “Awaiting a New Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, 60, No. 2 (February 7, 2013).

[2] Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis, (New York: Scribner’s, 1994), p. 3.

[3] Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen, For the law, neuroscience changes nothing and everything, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London B (2004) 359: 1781.

[4] Richard Dawkins, “Let’s all stop beating Basil’s car,” http://edge.org/q2006/q06_9.html.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Sven Birkerts, The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age (Boston: Farber and Farber, 1994), p. 120.

[7] This argument is from Erwin Schrödinger, What is Life? with Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 153. Also see C. F. von Weizsäcker, The History of Nature, trans. Fred D. Wieck (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949), pp. 142‑43.

[8] Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis, (New York: Scribner’s, 1994), p. 24.

[9] J. Y. Lettvin, H. R. Maturana, W. S. McCulloch, and W. H. Pitts, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers 47 (November 1959): 1940.

[10] Figure 15.1 is a composite of Shutterstock images: Michiel de Wit, “Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens);” Africa Studio, “Fishhook with worm isolated on white background;” Irink, “Bee isolated on white;” Anneka, “Mealworm or worm on a fishing hook as bait;” and Vnlit, “Dragonfly macro isolated on white background.”

[11] Jacob von Uexküll, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, trans. Alexander Dru (New York: Mentor, 1963), p. 86.

[12] Konrad Lorenz, On Aggression (New York: Harcourt & World, 1963), pp. 117-118.

[13] Konrad Lorenz, King Solomon’s Ring (New York: Crowell, 1952), p. 140.

[14] Wolfgang Kohler, The Mentality of Apes, trans. Ella Winter (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1931), pp. 320-321.

[15] Francine G. Patterson, “Conversations with a Gorilla,” National Geographic 154 (October 1978): 456, 459.

[16] Uexküll, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, p. 85.

[17] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales (New York: 1998), p. 9.

[18] Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus & Other Essays, trans. Justin O’Brien (New York: Vintage Books, 1955), p. 11.

[19] Steven Weinberg, The First Three Minutes: A Modern View of the Origin of the Universe (New York: Basic Books, 1977), p. 154.

[20] Uexküll, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, p. 85.

[21] Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, trans. Martin Milligan, in The Marx-Engels Reader, ed. Robert C. Tucker (New York: Norton, 1978), p. 89.

[22]F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Collier Books, 1980 [1925]), p. 182.

[23] Aristotle, De Anima, Bk. III, Ch. 8, 431b.

[24] Chandogya Upanishad, 6.12-14.

[25] Thomas Aquinas, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, p. 88.

[26] Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (Jerusalem: Keter, 1974), p. 152.

[27]Jalaluddin Rumi, Signs of the Unseen: The Discourses of Jalaluddin Rumi, trans. W. M. Thackston, Jr. (Putney, Vermont: Threshold Books, 1994), p. 59.

[28]Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching, No. 16.

[29] Billy Yellow, interview by David Maybury-Lewis, Millennium, aired on PBS, 1992.