|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

The Starting Point

Most of us are children of unhappy marriages, so we knew from suffering in early life, say by the age of seven or eight, that the human relations around us were failed marriages, parents abandoning their children, and the betrayal of friendships. We saw that material prosperity and career advancement were hogwash, for they were not the path to happiness as promised. We knew what we wanted most of all, unconditional love, although we may not have had the vocabulary to express this universal desire. Later in life, most of us settled for the earned love that good grades, a great career, and wealth bring about, although we wanted to be loved for who we are, not for what we possess.

The first need of a child is unconditional love. If a mother showers the baby with unconditional love, the infant feels, “I am wonderful just because I am.” The child learns to love himself the way the mother loves him. The young child then extends this self-love to love of the world. The child feels, “It’s good to be alive; it’s good to be surrounded by such good things.” Many a child’s life has been saved from ruin by the sustained, unconditional love of a grandmother, an aunt, or a nanny.

Psychoanalyst Erich Fromm observes that “unconditional love corresponds to one of the deepest longings, not only of the child but of every human being.”[1] Billy Joel captures the adult desire for unconditional love in his Just the Way You Are.

A child nurtured and protected by love can suffer the most outrageous misfortunes as an adult and still believe she and the world are fundamentally good. If success is measured by human relations and friendships, not wealth and career achievement, then the kind of love a child receives is a better predictor of her course in life than the environment, IQ tests, or genes.

We, thus, arrive at the most fundamental principle of human life: By nature, every person is meant to love and be loved. We lived this principle from the first day of life. Reading books or taking a college course in childhood development may have given us the vocabulary to express our nature, not the desire for unconditional love that was not chosen but part of us from day one.

Our Spiritual Nature

Surprisingly, the study of the perceptual life of frogs revealed the spiritual nature of Homo sapiens. In a classic study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lettvin, Maturana, McCulloch, and Pitts inserted tiny electrodes into a living frog’s optic nerve to measure the electrical impulses traveling to the frog’s brain. Using this technique, the researchers formed a good picture of what the frog sees. They found that when a small object is brought into the frog’s field of vision and left immobile, the frog’s eye sends electrical impulses to the brain for a minute or so, but then ceases to do so. After a short time, then, the object is no longer there as far as the frog is concerned.

The reason for this disappearance is that the frog’s retina is designed to detect small moving objects. If a small object ceases to move in the frog’s field of vision, its retina cancels it out of the frog’s world. Furthermore, the retina’s circuitry computes the velocity and trajectory of a small moving object so that the frog can aim its tongue ahead of where the object actually is.

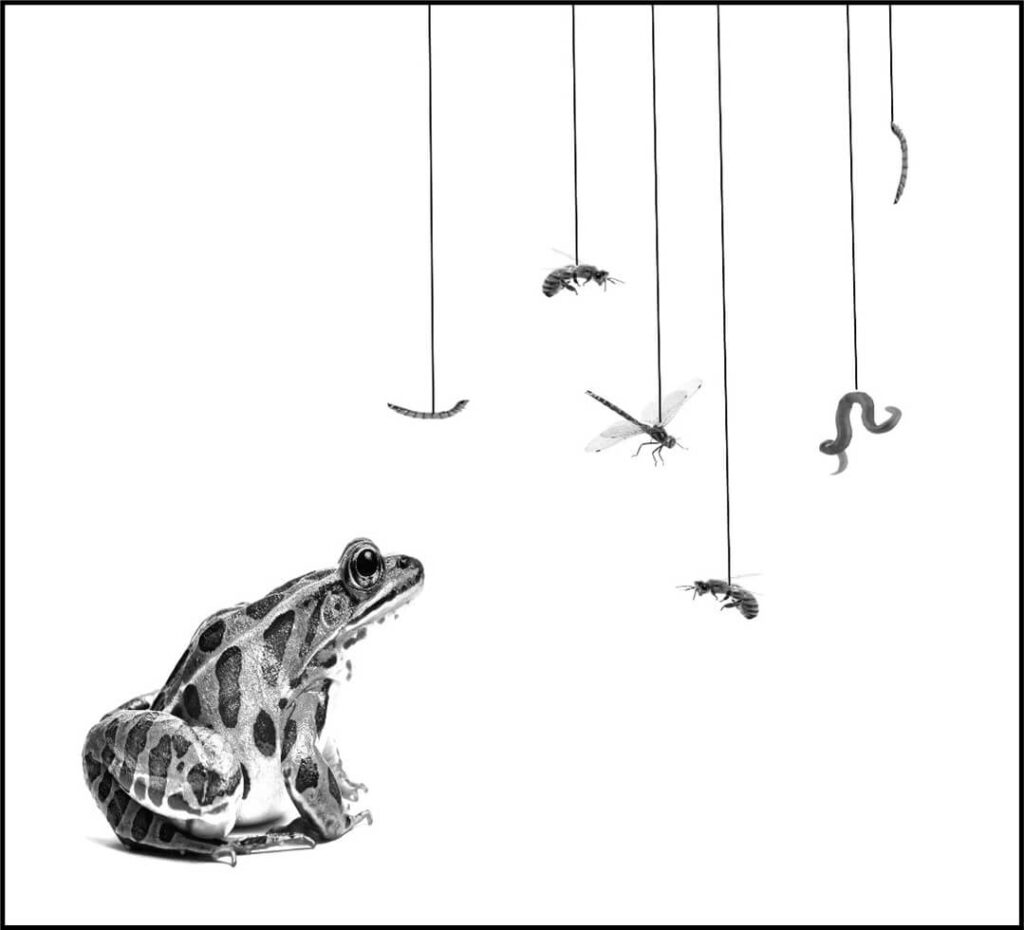

The researchers reported that “the frog does not seem to see or, at any rate, is not concerned with the detail of stationary parts of the world around him. He will starve to death surrounded by food if it is not moving. His choice of food is determined only by size and movement. He will leap to capture any object the size of an insect or worm, providing it moves like one. He can be fooled easily not only by a bit of dangled meat but by any small object.”[2] A frog cannot see a fly as such; it sees small moving objects. (See illustration.[3])

The MIT researchers also discovered nerve fibers that respond to the net dimming of light. These specialized fibers alert the frog to the danger of a nearby large moving object. The frog’s eye has only two categories: “my predator” and “my prey.”

Similarly, ethologist Jacob von Uexküll, among the first to document the remarkable specificity of animal perception, discovered that a jackdaw is unable to see a grasshopper that is not moving: “A jackdaw simply does not know the shape of a motionless grasshopper and is so constituted that it can only apprehend the moving form. That would explain why so many insects feign death. If their motionless form simply does not exist in the field of vision of their enemies, then by shamming death, they drop out of that world with absolute certainty and cannot be found even though searched for.”[4]

The narrowness of animal perception can produce astonishing results. Here is one of the hundreds of instances discovered by ethologists. A deaf turkey hen will peck all her chicks to death as soon as they are hatched. The distressed cheeping of the chicks is the only stimulus that inhibits the hen’s natural aggression in defense of her nest. The cheeping alone evokes a maternal reaction in the hen. Without the cheeping, a chick is judged by instinct to be an enemy and is attacked. A hen with normal hearing will attack a realistic stuffed chick if it emits no sound and is pulled toward the nest by a string. Conversely, she will respond maternally to a stuffed weasel (the turkey’s natural enemy) if it has a built-in speaker that produces the cheeping of a turkey chick.[5] Just as the frog cannot see a fly, the mother turkey cannot see its offspring!

The great discovery of ethology is that animals do not perceive what things really are; an animal’s perception is limited to a few key elements that will cause it to act. Uexküll summarizes the scientific study of animal perception with a powerful metaphor: An animal’s world is not the world we see but more closely resembles “a small, poorly furnished room.”[6]

Of all the natural creatures, only human beings can grasp a whole. The study of animal perception re-discovered the spiritual nature of Homo sapiens—the capacity to be connected to all that is, a fundamental principle of every wisdom tradition.

Ancient Greek: “The human soul is, fundamentally, everything that is.”[7]

Hindu: “Thou are that.”[8]

Christian: “Every other being takes only a limited part of being whereas the spiritual soul is capable of grasping the whole of being.”[9]

Jewish: “At opposite poles, both man and God encompass within their being the entire cosmos. What exists seminally in God unfolds and develops in man.”[10]

Islamic: “Who knows his soul knows his Lord.”[11]

Chinese: “He who cultivates the Tao is one with the Tao.”[12]

Native American: “To walk the path of beauty, you must connect to all things, take them seriously, with reverence.”[13]

We Are Social by Nature

The newborn infant reveals the social nature of Homo sapiens. In 1961, ethologist Robert Fantz developed a reliable technique for measuring the visual preferences of babies. Presenting a reclining infant with two visual stimuli, he measured the time each object was reflected in the infant’s pupils. In this way, Fantz could infer the baby’s preference for one object over another. It is now known that newborn vision is at least 20/150, an acuity not exceeded by many adults: “By demonstrating the existence of form perception in very young infants, [Fantz] . . . disproved the widely held belief that they are anatomically incapable of seeing anything but indistinct blobs of light and dark.”[14]

Fantz and many subsequent experimenters found clear evidence that babies, even those less than twenty-four hours old, prefer to gaze at a human face more than any other object, whatever its color, shape, or pattern. Other investigators found that “the human voice, especially the higher-pitched female voice, is the most preferred auditory stimulus in young infants.”[15] These preferences are clearly not learned: In one study, the youngest babies were ten minutes old.

In other experiments, Fantz showed that without learning or experience, a newly hatched chick prefers to peck at three-dimensional, round, small objects. Nature directs the chick to look for grain. Similarly, as soon as the human infant emerges from the womb, it looks for a human face and listens for a soprano voice. Nature directs the infant to seek its mother. The very first experience in a person’s life is connecting himself or herself to another person.

Without language, without others to learn language from, the mental capacities that Ms. Helen Keller, you, and I were born with would not have developed, and our lives would not have been much higher than that of a chimpanzee or a bonobo.[16] The language my children learned at home was not unique to our family or neighborhood. Learning English connected them to a larger community with much in common. Conservative estimates place the number of native speakers of English at 365 million; an additional 510 million use English as a second language; and, if a lower level of language fluency is included, then over one billion persons, an eighth of the world’s population, speak English. The number of people my children can easily communicate with is staggering.

The Curse of Social Living: The Obstacles to the Transcendent

Sophocles enunciated 2,500 years ago that “nothing that is vast enters the life of mortals without a curse;”[17] said in colloquial English, Nothing great without a curse.

The curse of social living is that every society implants ideas and instills habits of thinking and feeling that limit its members to a particular perspective, one that, as a general rule, is contrary to human nature and destructive to neighboring societies. The paradox is that social living greatly extends our capabilities and yet limits us. Capitalism tells us that we are economic beings, consumer-workers; nationalism tells us that our ultimate destiny is the fate of our Nation-State; democracy tells us we are autonomous, isolated individuals.

Individualism

Alexis de Tocqueville captured in one word the essence of Modernity. He was the first person to use the word “individualism” and reported “that word ‘individualism,’ which we coined for our own requirements, was unknown to our ancestors, for the good reason that in their days every individual necessarily belonged to a group and no one could regard himself as an isolated unit.”[18]

Jacob Burckhardt, the great scholar of the Italian Renaissance, explains that in Medieval Europe a “man was conscious of himself only as a member of a race, people, party, family, or corporation.”[19] When asked, “Who are you?”, a person may have replied, “A Vignola from Padua, a stone carver, and a good Christian.”

The Latin word “indīviduum,” the root of the English word “individual,” means an indivisible whole existing as a separate entity. Individualism is contrary to nature, for there is not one single indivisible whole existing as a separate entity in the universe. Yet, we humans can believe and act as if we are separate entities, although we are always connected to others. Homo sapiens is the only species that can act contrary to its nature. All modern cultures, including American, are founded on individualism, an idea contrary to nature. According to the Ancient Greeks and most traditional cultures, to live opposed to nature always ends in disaster.

In everyday life, we Americans exhibit a profound disconnection from our fellow citizens. We Americans move away from our families, do not know our neighbors, and get accustomed to walking down the same crowded streets every day without looking anyone in the eye. We are careful not to invade another’s personal space. If a stranger in a fast food restaurant asked us to share a booth, we would immediately perceive him as a threat or perhaps as mentally unbalanced; we are perfectly happy to sit alone in a swivel chair facing a blank wall.

Modernity: A Rebellion Against God

The beginning of the modern rebellion against God can be precisely dated: In October 1620, Francis Bacon, the principal architect of the experimental method of modern science,published The Great Instauration, a pamphlet that changed the world.[20]

In effect, Bacon rewrote the Bible. The Hebrew Bible told how Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden; the New Testament gave hope that what had been lost through disobedience to God would be restored at some point through faith in Jesus Christ. In Bacon’s version of Genesis, the restoration of the lost Paradise was expected to come about not through faith, but from the “great mass of inventions”[21] that would flow forth from the new experimental science that would give humankind the command over Nature that Adam had in the Garden of Eden. As a result, the descendants of the first man and woman could on their own return to Paradise and “subdue and overcome the necessities and miseries of humanity”[22] that resulted from the expulsion of Adam and Eve to East of Eden, where women painfully suffered childbirth, and the cursed ground brought forth thistles and thorns.

Without looking Him in the face, Bacon told God in sotto voce, “We do not need your help. We know now how to return ourselves to the Garden of Eden. Besides, we are tired of waiting; 1,600 years is too long.” After registering his complaint, Bacon gently nudged God aside.

The secular faith in grand schemes to institute Paradise on Earth, and in placing transcendent hope in human institutions has been destroyed by history. No theoretical arguments are necessary to show that the goal of a Heaven on Earth is perverse and that the pursuit of such a goal leads to untold death and destruction, to a Hell on Earth for tens of millions.[23] The sight of the rubble of Hiroshima, the smell of burning bodies in Auschwitz, and the sound of frozen corpses thrown on sleds in the Gulag destroyed secular faith. A technological utopia, a Master Race, and a classless society are nightmares from the past, only believable to a handful of science-fiction writers, to a few crazy ideologues blind to history, and perhaps to one or two drunks in bars near Harvard and M.I.T.

The Nation-State: The New God

With a stronger grip upon the soul of the citizens than any religion, the Nation-State made God the Ultimate Citizen. Shortly before World War I, Kaiser Wilhelm II claimed God bestowed upon him the care of the German Nation-State: “I look upon the People and the Nation handed on to me as a responsibility conferred upon me by God, and I believe, as it is written in the Bible, that it is my duty to increase this heritage for which one day I shall be called upon to an account. Whoever tries to interfere with my task I shall crush.”[24] For Kaiser Wilhelm II and his people, God is a German.

Horatio Bottomley, financier and Member of the English Parliament, in a speech at the London Opera House, September 14, 1914, claimed that the Prince of Peace and Progress sided with the British Empire: “It may be—I do not know and I do not profess to understand—that this is the great Audit of the Universe, that the Supreme Being has ordered the nations of the earth to decide who is to lead in the van of human progress. If

the British Empire resolves to fight the Battle cleanly, to look upon it as Something More than an ordinary war, we shall realize that it has not been in vain, and We, the British Empire, as the Chosen Leaders of the World, shall travel along the road of Human Destiny and Progress, at the end of which we shall see the patient figure of the Prince of Peace pointing to the Star of Bethlehem which leads us to God.”[25] For members of the British Empire, God is an English gentleman, and the global war will lead to the Prince of Peace.

The Nation-State, the new God—an idol—demands staggering sacrifices, previously unknown in the Christian era. The rolling French countryside around Verdun is covered with over one hundred thousand little, whitewashed crosses bearing the simple inscription “Mort pour la patrie.” Nearby the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial occupies a small part of the battlefield of the final offensive of World War I that cost the Americans 117,000 killed and wounded, the French 70,000, and the Germans 100,000. Yet, tens of millions of citizens still believe their destiny is to sacrifice themselves for the messianic future of their Nation-State.

Science: The Only Path to Truth

Science as the only path to truth invariably led to materialism. The toolbox of science is limited to air pressure, chemical changes, electrical impulses in nerves, brain cell activity, and other measurable properties of matter; the experimental method of science thus entails materialism.[26] Said in terms of modern reductionism, “the universe, including all aspects of human life, is the result of the interactions of little bits of matter.”[27] God is a fiction, not part of the scientific outlook.

Brain function alone cannot explain how we perceive red, much less that we imagine, think, and choose good over evil. The brain alone explains nothing about the interior life or about who we are.

Consider Schrödinger’s killer argument against materialism. Suppose sunlight is reflected from a red apple into the eye of a landscape painter. The sunlight passes through the lens of the eye and strikes the retina, a sheet of closely packed receptors—4.5 million cones and 90 million rods. Activated by the incoming sunlight, chemical changes occur in the rods and cones, which are then translated into electrical impulses that travel along the optic nerve to the brain. Further electrical and chemical changes take place in the brain. This description is complete in terms of the physiology of seeing; however, the sensation red has not appeared in this materialistic account of perception. The landscape painter experiences the red of the apple, not the various chemical and electrical changes necessary for seeing. Therefore, materialism is wrong.[28]

The Ultimate Question: Who Am I?

Impermanence

The impermanency of all things is an indisputable principle. Civilizations rise and fall; species of plants and animals come and go; continents drift and produce mountain ranges; wind and water erode rock and level mountains. Twentieth-century cosmologists discovered that the universe itself is destined to end with the Big Freeze, a cold eventless state of electrons, neutrinos, antielectrons, and antineutrinos. We are born, walk around for a while, and then disappear. Everything and everyone we love changes inevitably, decays, dies, and vanishes. Nothing lasts. All this is indisputable.

A friend of mine told me, “With my sister, I sat at my father’s bedside as he stopped breathing and tried to understand that he was no longer there, our father. What had become of all he’d known? All that reading of Great Books—sixty years of annotated books, all that was left of a lifetime of thought.”[29] The answer: Gone forever.

The eleventh-century Chinese scholar-poet Su Tung-po compared all human endeavors to the footprints left by geese on snow:

To what can our life on earth be likened?

To a flock of geese,

Alighting on the snow.

Sometimes leaving a trace of their passage.[30]

We Are Not Our Memories

While ancient theologians such as Augustine and Aquinas spoke of the soul’s immortality, New World Christians proclaim that the self is immortal. When a bereaved self asks a priest or pastor, “Will I see my loved one again?”, the answer is invariably “Yes,” with the implication that the desires, habits, and memories of the loved one are either immortal and live on now or will be resurrected in Christ. C. S. Lewis, a New World Christian apologist, even argued (hoped or believed) that his favorite dog would be resurrected with him.[31]

Margaret Guenther, retired director of the Center for Christian Spirituality of the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church, imagines, “Maybe the next life will be a feast for the mind, like great expanses of time in the main reading room in the Library of Congress, only with good lighting and comfortable chairs. Maybe it will be bountiful, like the homecoming picnics at the Martin City Methodist Church, where my father worshiped as a boy.” She confesses, “Sometimes I play with the idea that I will see my grandfather, whom I loved deeply and who died when I was nine, and meet my German grandparents for the first time. . . . Maybe I can have a beer with Meister Eckhart or crochet and chat with Dame Julian of Norwich, while she sews on humble garments, suitable for anchorites.”[32]

Implicit in Guenther’s picture of the next life is her answer to the most fundamental question a person can ask—“Who am I?” Guenther gives the common answer—I am my memories, a view that does not hold up to scientific or philosophical examination.

Memories not only fade but they are also changed in many ways. The mere telling of an episode of our life narrative to others changes that memory; we enhance those memories that others respond to positively and downplay or edit out those that others dislike.

When a young mother shows her child pictures on her cell phone of their trip to Disneyland and says, “Annie, you had such a great time talking to Mickey Mouse; that was the best part of your summer,” she is implanting a memory in her child.[33]

Memories are not like a read-only computer file stored in the brain; remembering is not like retrieving an uncorrupted digital document of our history accurately and permanently recorded. Daniel Offer and his colleagues at the Northwestern University Medical School examined “the differences between memories adults had of their teenage years and what they actually said when they were interviewed as adolescents” thirty-four years before. “The subjects’ recollections were about the same as would have been expected by chance . . . the accuracy of recalled memories was uniformly poor.”[34]

Two summers ago, I visited a friend who lives in Provincetown, Massachusetts. When I returned to Santa Fe from Cape Cod, I had vivid, physical memories; I could feel my toes in beach sand, the glaring sun in my eyes, and the smell of the sea. The more I told these memories to myself and my friends, the weaker the concrete memories became; until now, they exist only in speech.[35] With the possible exceptions of wine connoisseurs, painters, and musicians, most of whom maintain that certain things are better left unsaid, verbalization erodes concrete experience until it is replaced by speech.

The Self: A Cultural Construct

I was not born speaking English or Romanian, nor did I know Newton’s three laws or the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution. I was not born with a self; even when I was two, there was no Georgie Stanciu. Child psychologists have observed that around 19 months, a child begins to use the words “my,” “mine,” and “me” and his name with a verb—“Georgie eats.”[36] By 27 months, self-reference is common, although the child is not telling the parents who he is; that requires a narrative. Between three to five years of age, autobiographical memory emerges, and the development of a unique personal history begins.[37]

I was born into a world of complex social relations; others instructed me how to behave and taught me what was important in life; in effect, the world gave me a self and assigned me a unique node in a social web. My parents and relatives taught me that I was part of a Romanian community with indissoluble obligations to others.

Who Am I? Redux

I was born in Pontiac, Michigan, and christened George Stanciu, but suppose at two months, I was adopted by the Li family, and they moved to Beijing, China, their home city. My new family named me Li Zhang Wei. That my given name Zhang Wei was second indicated I was first a member of the Li family or clan.

Zhang Wei’s parents emphasized interdependence, group solidarity, social obligation, and personal humility. Zhang Wei was taught obedience, proper behavior, emotional restraint, and the value of group harmony. He understood himself in terms of his relation to a whole, to the Li family, to Chinese society, and, perhaps, to the Tao. “In Confucian human-centered philosophy, man cannot exist alone,” philosopher Hu Shih writes. “All action must be in the form of interaction between man and man.”[38] Zhang Wei always saw himself as part of a larger whole. In the Chinese language, there is no word for “individualism;” the closest word is the one for “selfishness.”[39]

If I were not adopted, my European-American parents often focused on my attributes, preferences, and judgments, making Georgie an individual. Parents in America aim to develop an autonomous self and thus encourage independence, assertiveness, and self-expression in their offspring. Georgie was taught to “stick up for his rights and to fight his own battles.”

In grade school, Georgie was trained in the ethos of capitalism. He competed with his fellow students to get the best grades and the most gold stars. In this way, Georgie learned I succeed only if someone else fails, and the converse—if someone else succeeds, I must have failed. Another lesson he learned was that my success is entirely due to me, and no other person has a legitimate claim on its benefits—a fundamental ethic of capitalism, where each person is responsible for his or her own success or failure.

By the end of the sixth grade, Georgie understood himself as an autonomous, isolated individual.

Both Li Zhang Wei and George Stanciu took their culturally-constructed selfs to be who they really were. While George took himself to be the center of the universe and Zhang Wei did not, both had natural self-love, although George’s self-love was greatly enhanced by his individualistic culture.

In a roundabout way, I arrived at the central insight of the Buddha—the self is an illusion. In the Deer Park at Isiptana, the Buddha preached his second sermon, The Discourse on Not-Self, and “while this discourse was being spoken, the minds of the monks of the group of five were liberated from the taints by nonclinging.”[40] Arguably, anattā, a Pāli word that literally means no-self, is the most important and most challenging concept in Buddhism since it led the five monks to instant enlightenment, to Nirvāṇa, to “the annihilation of the illusion [of self], of the false idea of self.”[41]

If each one of us were merely a particular compound of body, sense perceptions, memories, and ideas, then no escape from Samsara, the never-ending wheel of birth and death, would be possible. The Buddha told his disciples, “There is, monks, an unborn, not become, not made, uncompounded . . . therefore an escape can be shown for what is born, has become, is made, is compounded.”[42] I had no idea what the Buddha meant by the unborn, so I suspected my answer to “Who am I?” missed an essential element of who I am.

In some mysterious way, I was more than my memories, which by themselves, without storytelling, were disconnected, and more than my self-narrative, whose central plot was my adolescent rebellion against all authority.

Of course, the unborn within me, my true self, was a complete mystery, so after stumbling around for years exploring Hinduism and Buddhism, I turned to the deepest understanding of the human person that Christianity offers.

The Unnamable

The Patristic Fathers embraced the theological insights of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopogite: God is not any of the names used in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, not God of gods, Holy of holies, Cause of the ages, the still breeze, cloud, and rock.[43] God is not Mind, Greatness, Power, or Truth in any way we can understand, for He “cannot be understood, words cannot contain him, and no name can hold him. He is not one of the things that are, and he is no thing among things.”[44] God is the Unnamable.

According to St. Gregory Palamas, we know the energy of God, not His essence: “Not a single created being has or can have any communion with or proximity to the sublime nature [of God]. Thus, if anyone has drawn near to God he evidently approached Him by means of His energy.”[45] A person becomes close to God by participating in His energy, “by freely choosing to act well and to conduct [himself] with probity.”[46] Here, Gregory distinguishes between God’s essence, or substance (ousia), and His activity (energeia) in the world. The energy of God is experienced as Divine Light, such as the light of Mount Tabor or the light that blinded St. Paul on the Road to Damascus.

Given this understanding of God, the image of God within us means that the essence of each one of us is unnamable and that we are known to others only through our activity in the world, that is, through a socially constructed self. We are unknowable to ourselves, although through meditation, or what the Patristic Fathers called contemplation, we can witness our thoughts, memories, and storytelling and thus know that we are not what we witness. Through more advanced contemplation, we may experience Divine Light, the presence of God.

At the core of our being is the unnamable, the “empty mind” of Zen Buddhism, the “pure consciousness” of Hinduism, and the “spirit” of Christianity, although all words ultimately fail to capture our true self. We, the unenlightened, believe that the false self given to us by culture is permanent and fail to see that the false self is an illusion, with no more permanency than a smoke ring, destined to vanish with the death of the body. Because we take our culturally-given self for our true self, we fail to experience who we truly are. Our true self is always present, completely perfected, with no need for development from us; we must merely step aside. Every spiritual master calls for the death of self and a spiritual rebirth beyond egoistic desires, beyond religious practices, beyond any given culture, beyond the dictates of society, into the law of love, and into compassion for every living being.

Jesus told his followers, “He who loves his life loses it, and he who hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life.”[47] St. Paul confesses, “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me . . .”[48]

St. Paul’s confession is a mystery to us ordinary mortals; we struggle to understand his straightforward but mysterious description of his new life. Perhaps, the best place to begin is with “it is no longer I who lives,” that is with the death of Saul; recall before St. Paul’s conversion to Christianity, he was Saul, a persecutor of the early disciples of Jesus. On the road to Damascus to persecute Christians, a light flashed about Saul; he fell to the ground and heard a voice, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” Saul was blind for three days; when he recovered his sight, a new person was born, Paul, who became instrumental in explaining Jesus’ message to the world.

We will call the birth of a new person through mystical experience, intellectual insight, or intense suffering Christian enlightenment. For skeptical non-Christians, Homer, in the first great book of Western civilization, gives a precursor of Christian enlightenment.

At the opening of the Iliad, Achilles is angered because Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek expedition to Troy, has taken for himself Briseis, a beautiful and clever woman captured by Achilles. Since Achilles thinks he is the greatest warrior amongst the Greeks, he feels dishonored by Agamemnon, retires to his ship, and refuses to join in the battle against the Trojans. Blinded by his anger, Achilles allows his best friend, Patroclus, to use his armor and do battle against the Trojans. Patroclus, masquerading as Achilles, is killed by Hector, the greatest Trojan warrior. Achilles goes berserk—enters battle, kills every Trojan in sight, including Hector, and in his rage attacks a river, the height of madness.

From Achilles’ immense suffering, a new person emerges. He sees that he has been like other men—foolish, caught up in winning prizes, striving for eternal glory. The new Achilles is compassionate and even smiles at the foibles of his fellow warriors.[49] Eva Brann, classics scholar and recipient of the National Humanities Medal, is surprised that “with the unaccountable suddenness of a divinity, Achilles is another being: the courtly, peace-keeping, tactful, and generous host at Patroclus’ funeral games.”[50]

The last event of the funeral games for Patroclus is spear-throwing. Agamemnon and Meriones step forward to compete for “a far-shadowing spear and [for the first prize] an unfired cauldron with patterns of flowers on it, the worth of an ox.”[51] The Iliad is about to begin over again, this time with Agamemnon taking a prize from Meriones. With a newly acquired wisdom, Achilles intercedes to stave off an intense conflict between the ruler and the ruled. Achilles tells Agamemnon, “For we know how much you surpass all others; by how much you are greatest for strength among the spear-throwers, therefore take this prize and keep it and go back to your hollow ships; but let us give the spear to the hero Meriones.”[52]

What follows next are the two most remarkable lines in the Iliad. Achilles, no longer seeking honor and prizes, entreats Agamemnon, “If your own heart would have it this way, for so I invite you [to give the spear to Meriones].” Achilles spoke, “nor did Agamemnon lord of men disobey him.”[53]

Achilles has become a wise ruler of men.

Homer shows us in the Iliad that suffering can destroy a person’s ego, correct his misunderstanding of himself, and join him more profoundly to others. Suffering can move a person from narrow self-love to an expansive love of others.

Homer’s insight that we are not determined by fate or culture but can free ourselves from our ill-formed habits and faulty thinking, often through suffering, to connect ourselves to others is an essential part of the Western understanding of the human person. For example, James Baldwin, an American Black writer, citing contemporary experience, agrees with Homer: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was Dostoevsky and Dickens who taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or whoever had been alive.” The following words of Baldwin could have been spoken by Achilles, “Only if we face these open wounds in ourselves can we understand them in other people.”[54]

The Western tradition that from immense suffering, a new person can emerge rests on nature; every human being comes into this world through suffering. A woman in labor experiences intense pain and willingly accepts the risk of death. Once floating contentedly in amniotic fluid, the fetus feels the rhythmic contraction of the uterus and begins the difficult and painful passage through the birth canal to air, light, and a new life.

The image of God within us also means that each of us has the energy to transform the physical and social worlds we inhabit, either for good or evil. For instance, we are free to use the fruits of science for the benefit of life or the destruction of humanity, for creating polio vaccine or thermonuclear weapons, aids for life or instruments of death. Through such free choices, we either draw closer to God or become more distant from Him.[55] We become what we choose.

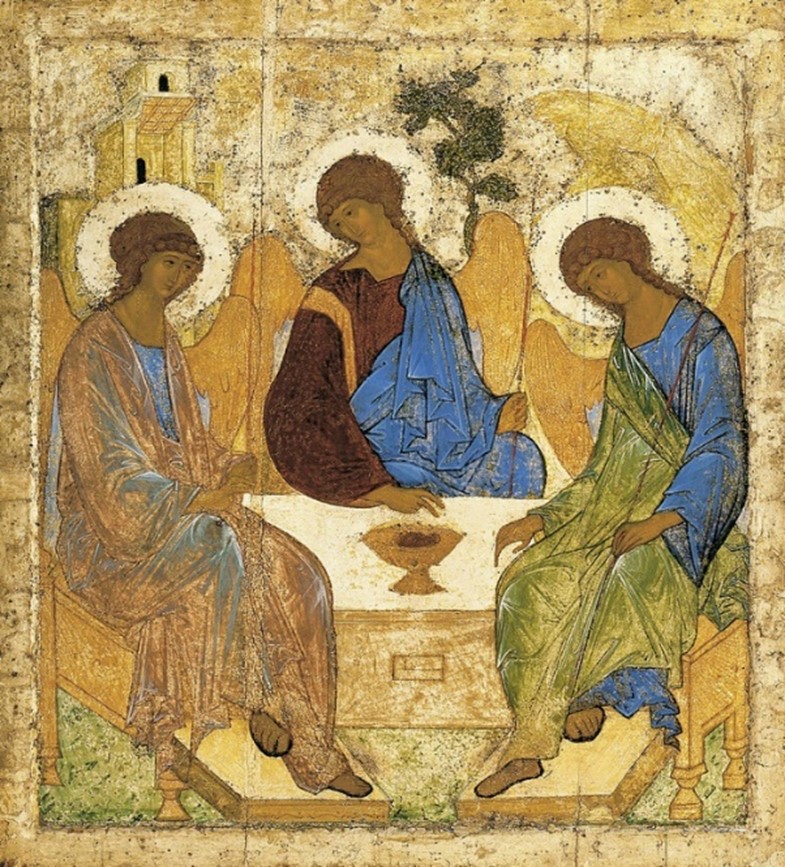

Our freedom is virtually unlimited; we can thumb our nose at God, refuse to become who we truly are, and embrace a self of our own choosing. However, to freely abandon God, to exist in oneself, and to seek satisfaction in one’s own being is not quite to become a nonentity but is to verge on non-being.[56] Hell is not the fiery pit of received Christianity, but the complete separation from God—forever. Heaven is not the reuniting with one’s favorite dog or the blissful meeting with one’s unknown relatives or the pleasure of conversing with the saints, not such “enthusiastic fantasies,” but to “know more deeply the hidden presence by whose gift we truly live.”[57] Heaven is joining the Holy Trinity in Love, as wonderfully expressed in the icon The Trinity, also called The Hospitality of Abraham, by Andrei Rublev. (See illustration.)

The three angels in the icon are metaphors for the three persons of the Holy Trinity. The figures are arranged so that the lines of their bodies form a full circle. In motionless contemplation, each angel gazes into eternity. Because of inverse perspective, the focal point of the icon is in front of the painting on the viewer; Rublev is inviting the viewer to engage in an amazing spiritual exercise, to complete the circle of angels, to join in a union with the Holy Trinity, to become a “partaker of divine nature.”[58] Many Church Fathers were fond of telling their brethren, “God became man so that man might become God.” I could not turn down such an invitation.

Like every person, I live in two worlds, the temporal and the eternal. I love the taste of lamb curry, the sound of the cello, and the fall foliage of New England, and I wonder about the abundant beauty of Nature, where nothing is not beautiful, either to the eye or to the mind. Yet, this physical world, like “George Stanciu,” is transient and eventually vanishes without leaving a trace.

I live among the rich and the poor, the powerful and the weak, the ambitious and the lazy, the good and the bad, the loving and the hateful. Grappling with death taught me how to live in this world. I now see that every person I meet in ordinary, daily affairs—the mailman, the bank teller, the butcher at Whole Foods, the obnoxious teenager down the street with his blaring boom box—is part human and part divine, a storytelling self, often confused, dislikable, and in pain, but always transient, and a mysterious self, deathless, an image of God, worthy of unconditional love.

The main image is a photograph by jpleno and is used here courtesy of Pixabay.

This essay first appeared at The Imaginative Conservative, September 2023.

Endnotes

[1] Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (New York: Harper, 2006 [1956]), p. 39.

[2] J. Y. Lettvin, H. R. Maturana, W. S. McCulloch, and W. H. Pitts, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers 47 (November 1959): 1940.

[3] Figure 15.1 is a composite of Shutterstock images: Michiel de Wit, “Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens);” Africa Studio, “Fishhook with worm isolated on white background;” Irink, “Bee isolated on white;” Anneka, “Mealworm or worm on a fishing hook as bait;” and Vnlit, “Dragonfly macro isolated on white background.”

[4] Jacob von Uexküll, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, trans. Alexander Dru (New York: Mentor, 1963), p. 86.

[5] Konrad Lorenz, On Aggression (New York: Harcourt & World, 1963), pp. 117-118.

[6] Uexküll, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, p. 85.

[7] Aristotle, De Anima, Bk. III, Ch. 8, 431b.

[8] Chandogya Upanishad, 6.12-14.

[9] Thomas Aquinas, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, p. 88.

[10] Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (Jerusalem: Keter, 1974), p. 152.

[11]Jalaluddin Rumi, Signs of the Unseen: The Discourses of Jalaluddin Rumi, trans. W. M. Thackston, Jr. (Putney, Vermont: Threshold Books, 1994), p. 59.

[12]Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching, No. 16.

[13] Billy Yellow, interview by David Maybury-Lewis, Millennium, aired on PBS, 1992.

[14] Robert Fantz, “The Origin of Form Perception,” Scientific American 204 (May 1961):69.

[15] Daniel G. Freedman, Human Infancy: An Evolutionary Perspective (Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum, 1974), p. 30.

[16] See George Stanciu, 11 Quantum Physics and Mind of The Great Transformation: How Contemporary Science Harmonizes with the Spiritual Life or Quantum Physics and Mind.

[17] Sophocles, Antigone, trans. R. C. Jebb, line 614. Available http://classics.mit.edu/Sophocles/antigone.html.

[18]Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Régime and the French Revolution, trans. Stuart Gilbert (New York: Doubleday, 1955 [1856]), p. 96.

[19] Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans. S. G. C. Middlemore (New York: Modern Library, 1954), p. 100.

[20] See George Stanciu, George Stanciu, The Great Transformation: How Contemporary Science Harmonizes with the Spiritual Life, Ch. 13 Paradise on Earth.

[21]Ibid., p. 103.

[22] Ibid., p. 23.

[23] A partial, conservative catalog of the political murders of the twentieth century is mind-boggling, unbelievable, but sadly undeniable. Deaths: World War I (military only): 9,700,000; Russian Revolution and Civil War: 9,000,000; forced collectivization: 3,000,000 Ukrainian peasants; Russian gulag: 1,000,000 political prisoners; Spanish Civil War: 1,200,000; World War II (military and civilian): 51,000,000; Nazi camps: 6,000,000 Jews and 6,000,000 Slavs, Gypsies, and political prisoners; Japanese Rape of Nanking: 300,000 Chinese; Allied bombing of Hamburg, Berlin, Cologne, and Dresden: 500,000 German civilians; Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 140,000 Japanese civilians; Vietnam War (military and civilian): 5,000,000; Chinese Great Leap Forward: 30,000,000. These numbers are low estimates. For the difficulty of estimating mass political murders, see Lewis M. Simons, “Genocide and the Science of Proof,” National Geographic Magazine (January 2006): 28-35 and Timothy Snyder, “Holocaust: The Ignored Reality,” The New York Review of Books (July 16, 2009).

[24] Kaiser Wilhelm II, quoted in Voices from the Great War, ed. Peter Vansittart (New York: Franklin Watts, 1984), p. 4.

[25] Horatio Bottomley, ibid., pp. 40-41. Capitals in the original.

[26] For a detailed discussion, see George Stanciu, The Great Transformation: How Contemporary Science Harmonizes with the Spiritual Life, Ch. 9, Dumb Idea # 3: Materialism.

[27] H. Allen Orr, “Awaiting a New Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, 60, No. 2 (February 7, 2013).

[28] In the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, materialism is also wrong, for undivided wholeness, in which the observing instrument is not separated from what is observed, means the mind, human and divine, is an essential element of the universe. See

[29] See Kathryn Kramer, Missing History: The Covert Education of a Child of the Great Books, (Corinth, Vt.: Threshold Way Publishing, 2015), pp. 200-201.

[30] Su Tung-po, “Remembrance.” Available https://mypoeticside.com/poets/su-tung-po-poems.

[31] C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1962), Ch. 9.

[32] Margaret Guenther, “God’s plan surpasses our best imaginings,” Episcopal Life (July/August 1993).

[33] For a scientific study of implanted memories, see I. E. Hyman Jr. and J. Pentland, “The Role of Mental Imagery in the Creation of False Childhood Memories,” Journal of Memory and Language (1996) 35 (2): 101–17.

[34] Daniel Offer, Marjorie Kaiz, Kenneth L. Howard, and Emily S. Bennett, “The Altering of Reported Experiences,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (June 2000), 39 (6): 735-42.

[35] See Jonathan W. Schooler and Tonya Engstler-Schooler, “Verbal Overshadowing of Visual Memories: Some Things Are Better Left Unsaid,” Cognitive Psychology 22 (1990): 36-71.

[36] Jerome Kagan, Unstable Ideas: Temperament, Cognition, and Self (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 233.

[37] Qi Wang and Jens Brockmeier, “Autobiographical Remembering as Cultural Practice: Understanding the Interplay between Memory, Self and Culture,” Culture & Psychology (2002) 8:52.

[38] Hu Shih, quoted by Ambrose Yeo-chi King, “Kuan-hsi and Network Building: A Sociological Interpretation,” Daedalus, 120 (Spring 1991): 65.

[39] Richard E. Nisbett, The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently . . . and Why (New York, NY: Free Press, 2003), p. 51.

[40] Anatta-lakkhana Sutta: The Discourse on the Not-self in In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pāli Canon, trans. Bhikkhu Bodhi (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2005), p. 342.

[41] Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught, (New York: Grove Press, 1974), p. 37.

[42] Burtt, ed., Teachings of the Compassionate Buddha, p. 113.

[43] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Divine Names in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 596A.

[44] Ibid., 872A.

[45] Gregory Palamas, Topics of Natural and Theological Science and on the Moral and Ascetic Life: One Hundred and Fifty Texts in The Philokalia, Vol. IV, ed. and trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1984), p. 382.

[46] Ibid., p. 383.

[47] John 12:25. RSV

[48] Galatians 2:20. RSV

[49] The Iliad of Homer, trans. Richard Lattimore (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1951), Bk. 23, line 555.

[50] Eva Brann, Homeric Moments: Clues to Delight in Reading the Odyssey and the Iliad (Philadelphia, PA: Paul Dry Books, 2002), p. 68.

[51] The Iliad of Homer, Bk. 23, line 885.

[52] Ibid., Bk. 23, lines 890-893.

[53] Ibid., Bk. 23, lines 894-895.

[54] James Baldwin, quoted by Jane Howard, “Doom and Glory of Knowing Who You Are,” Life magazine, 54, No. 21 (24 May 1963), p. 89.

[55] See Gregory Palamas, Topics of Natural and Theological Science and on the Moral and Ascetic Life: One Hundred and Fifty Texts in The Philokalia, Vol. IV, ed. and trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1984), p. 382.

[56] See Augustine, City of God, Bk. 14, Ch. 13.

[57] Joseph Ratzinger, Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, 2nd ed., trans. Michael Waldstein (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1988), pp. 233-234.

[58] 2 Peter 1:4. RSV