|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

All the Light We Can See

I live in Northern New Mexico, where at sunset, a golden light envelops the high desert; the adobe buildings glow with the richness of polished gold and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains with the deep red of blood. The extraordinary light, the sparseness of the high desert, and the clarity of the air have drawn thousands of painters and photographers to Taos and Santa Fe.

Every summer, my children and grandchildren, after a dinner of barbecued ribs and coleslaw, or Romanian chicken stew with tarragon and sour cream, or New Mexican beef enchiladas, sit outside to watch the sunset; I with a glass of Pinot Noir or Sauvignon Blanc and the grandchildren with Gerolsteiner mineral water. We chat aimlessly, enthralled by the sunlight and the incredible air, amazingly fresh after the usual brief monsoonal afternoon rain in July and August. Of all the senses, we delight most in sight, not just the brilliance of the sunset and the clouds changing from coral to deep red, but from the nearly palpable light the makes each tree, weed, and rock stand out, as if it alone existed in the universe. For a moment, we experience that it is great to be alive—to behold the miracle that we and trees, weeds, and rocks exist.

Watching the sun go down in New Mexico, we did not need Aristotle to tell us that “all men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves; and above all others the sense of sight. . . . we prefer seeing (one might say) to everything else. The reason is that this, most of all the senses, makes us know and brings to light many differences between things.”[1]

Sight: A Miracle

For laypersons and scientists alike, sight is a miracle. Textbooks typically gloss over the profound difference between sense perception and its necessary physical components. Francis Crick, the co-discoverer of the physical structure of the DNA molecule, admits, “We really have no clear idea how we see anything. This fact is usually concealed from the students who take such courses [as the psychology, physiology, and cell biology of vision].”[2]

Physicist Erwin Schrödinger argues that science is incapable of explaining how we see: “If you ask a physicist what is his idea of yellow light, he will tell you that it is transversal electromagnetic waves of wavelength in the neighborhood of 590 millimicrons. If you ask him: But where does yellow come in? He will say: In my picture not at all.”[3] Carl von Weizsäcker, also a physicist, agrees: “Light of 6,000 Å wavelength reaches my eye. From the retina, a chemicoelectrical stimulus passes through the optical nerve into the brain where it sets off another stimulus of certain motor nerves, and out of my mouth come the words: The apple is red. Nowhere in this description of the process, complete though it is, has any mention been made that I have had the color perception red. Of sense perception, nothing was said.”[4]

Although Schrödinger and Weizsäcker employ technical language, their insights into the nature of perception are based on straightforward observations. Let me restate their argument. Suppose sunlight is reflected from a red apple into the eye of a landscape painter. The sunlight passes through the lens of the eye and strikes the retina, a sheet of densely packed receptors—4.5 million cones and 90 million rods. Activated by the incoming sunlight, chemical changes occur in the rods and cones, which are then translated into electrical impulses that travel along the optic nerve to the brain. Further electrical and chemical changes take place in the brain. In terms of the physiology of seeing this description is complete; however, the sensation red has not entered this scientific account of perception. The landscape painter experiences the red of the apple, not the myriad chemical and electrical changes that are necessary for seeing.[5]

Neuroscientist Vilayanur Ramachandran, too, acknowledges that explaining vision in terms of brain function alone is an impasse for science: “No matter how detailed and accurate [the] outside-objective description of color cognition might be, it has a gaping hole at its center because it leaves out”[6] the experience of redness. He laments that the impasse results from a limit of present-day science: “Perhaps, science will eventually stumble on some unexpected method or framework for dealing with qualia—the immediate experiential perception of sensation, such as the redness of red or the pungency of curry—empirically and rationally, but such advances could easily be as remote from our present-day grasp as molecular genetics was to those living in the Middle Ages.”[7]

The brain is shrouded in darkness, even while a person perceives the brilliance of the sun’s glare. How a three-pound organ shaped like a giant wrinkled walnut, encased in a skull, gives rise to light is a mystery no one understands.

Plants Eat Light

For millennia, people believed that plants grow by transforming soil and manure into themselves until Jan Baptista van Helmont (1580-1644) did an experiment to determine where a plant gets its mass. He planted a five-pound willow tree in a pot of soil weighing 200 pounds. Five years later, the plant weighed 169.1 pounds and the soil 199.9 pounds. He had only watered the plant, so incorrectly concluded that the increased mass of the plant came from the water.

Several centuries later, Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) performed a simple, clever experiment that showed that plants produce oxygen. He put a mint plant in a closed container with a burning candle. The candle flame used up the oxygen and went out. After 27 days, Priestley was able to re-light the candle; thus, plants produce oxygen.

Building upon Priestley’s result, Jan Ingenhousz (1730-1799) used aquatic plants to demonstrate that plants undergo cellular respiration, but the opposite of animals—expelling oxygen and taking in carbon dioxide.

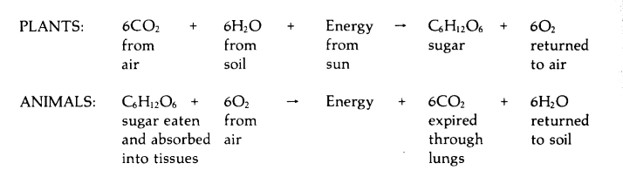

We now know that plants convert sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water into glucose and oxygen. The exquisite interdependence of plants and animals is wonderous. Each needs the products of the other. Plants use sunlight, the carbon dioxide in the air, and water from the soil to manufacture sugars, releasing oxygen as a byproduct. Animals consume plant sugars and oxidize them to produce energy, breathing back carbon dioxide into the air and returning water to the soil as urine. The cycle is perfect; nothing is wasted. The table below gives a simplified version of the chemistry involved and shows how plants eat light and how our biological life ultimately relies on light, whether we are vegetarians or not.

Intellectual Light

Every scientist and mathematician, professional and student, whom I have known, can give countless occurrences in their own lives of hard, fruitless labor preceding effortless knowing. In the classroom or around the seminar table, I have heard an excited “I see it” innumerable times, but never in my life as a theoretical physicist did I reflect with colleagues about the meaning of such an experience. As a result, for years, I remained in the dark about the deepest aspects of what we are. My enlightenment came only after reading Plato and Aristotle. Through straightforward reflection about the interior life, accompanied by clear thinking, Plato and Aristotle discovered two aspects of the mind, which they called nous and dianoia.

The Latin words ratio and intellectus correspond to the older Greek terms dianoia and nous. The Greek is used here because the Latin calls to mind the English words “reason” and “intellect,” which often are used as synonyms. The English words are substantially more limited and less precise than either the Latin or the Greek.

Labor

We commonly speak of knowing as defining, comparing, analyzing wholes into parts, and drawing conclusions from first principles. Such discursive or step-by-step thinking the ancient Greek philosophers called dianoia. Sherlock Holmes is the epitome of dianoia at work. From the analysis of a cigar ash ground into a carpet, a scuff mark on a door, and the residue in a wineglass, he concludes the criminal is a lame aristocrat who resides in Kensington.

In discursive thinking, we either apply first principles or draw out their consequences. Dianoia operates step-by-step, almost in a mechanical fashion, repeating the same procedure again and again: A = B, B = C, therefore A = C; premise 1, premise 2, therefore, conclusion 1; etc.

Gift

Nous is the capacity for effortless knowing—to behold the truth the way the eye sees a landscape. The most famous story of sudden insight—of the “light bulb going off”—is the one told about Archimedes.  The ruler Hiero II asked Archimedes to determine if the royal crown was truly made of pure gold or alloyed with silver. Archimedes knew that if the crown were not irregularly shaped, he could easily measure its volume and then check if its density was that of gold. But Archimedes could not figure out how to determine the volume of the crown. He was stumped; until one day when he stepped into his bath, the solution suddenly appeared to him: A given weight of gold displaces less water than an equal weight of silver. He shouted, “Eureka! Eureka!” and ran naked through the streets of Syracuse.

The ruler Hiero II asked Archimedes to determine if the royal crown was truly made of pure gold or alloyed with silver. Archimedes knew that if the crown were not irregularly shaped, he could easily measure its volume and then check if its density was that of gold. But Archimedes could not figure out how to determine the volume of the crown. He was stumped; until one day when he stepped into his bath, the solution suddenly appeared to him: A given weight of gold displaces less water than an equal weight of silver. He shouted, “Eureka! Eureka!” and ran naked through the streets of Syracuse.

Henri Poincaré, in his book Science and Method, describes how he discovered the relationship of Fuchsian functions to other branches of mathematics. After he had worked out the basic properties of Fuchsian functions he left Caen, France, where he was living at the time, to take part in a geological conference at Coutances. The incidents of the journey made him forget his mathematical work. As a scheduled break from the conference, attendees went on a bus excursion. Poincaré reports, “Just as I put my foot on the step [of the bus], the idea came to me, though nothing in my former thoughts seemed to have prepared me for it, that the transformations I had used to define Fuchsian functions were identical with those of non-Euclidean geometry.”[8]

When Poincaré returned home from the conference, he turned his attention to the study of certain “arithmetical questions without any great apparent result, and without suspecting that they could have the least connection with my previous researches. Disgusted at my want of success, I went away to spend a few days at the seaside, and thought of entirely different things. One day, as I was walking on the cliff, the idea came to me, again with the same characteristics of conciseness, suddenness, and immediate certainty, that arithmetical transformations of indefinite ternary quadratic forms are identical with those of non-Euclidean geometry.”[9]

Mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss tried unsuccessfully for two years to prove an arithmetical theorem. In a letter to a colleague, he revealed, “Finally, two days ago, I succeeded, not on account of my painful efforts, but by the grace of God. Like a sudden flash of lightning, the riddle happened to be solved. I myself cannot say what was the conducting thread which connected what I previously knew with what made my success possible.”[10]

Astrophysicist Fred Hoyle relates how the solution to what seemed an intractable mathematical problem in quantum physics came to him while driving a car on the road over Bowes Moor, much as “the revelation occurred to Paul on the Road to Damascus: My awareness of the mathematics clarified, not a little, not even a lot, but as if a huge brilliant light had suddenly been switched on. How long did it take to become totally convinced that the problem was solved? Less than five seconds.”[11]

What Hoyle describes as a “huge brilliant light” and Poincaré calls a “sudden illumination”[12] and Gauss terms “a flash of lightning,” the ancient Greek philosophers named nous, whose characteristics are “conciseness, suddenness, and immediate certainty,” as Poincaré noted. We, clearly, cannot command nous; the direct grasp of a truth is a gift, not something we can turn on or off at will, for if we could, we would.

To know in the deepest sense is not to possess accurate information, say the names of the anatomical parts of a rabbit, or to have a method that turns out correct answers, say a mass spectroscope that determines molecular masses. To know profoundly is to experience an insight, a revelation of a deep and significant truth. Such knowing cannot be summoned by the will, although insight is usually preceded by hard work and the clearing away of major errors and wishful expectations. Sometimes, insight occurs only after giving up. In contrast to the truths arrived at through hard labor, intuitive insights are gifts. Consequently, dianoia usually results in pride, nous almost always in gratitude.

The execution of Socrates and the crucifixion of Jesus raise the vexing question, “Why does truth sometimes call forth hatred?”, especially since no person knowingly embraces falsehood or says, “I believe this, although I know it is false.” The citizens of ancient Athens loved their city-state as the embodiment of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful. For its citizens, Athens was the apex of political and artistic life and consequently elevated each of its members to the highpoint of humanity in contrast to the barbarians of other city-states. Except for Homer and Hesiod, greatness belonged solely to the Athenians. To question Athens was to cast doubt on the preeminence of its citizens. The majority of Athenian blindly loved their polis and hated Socrates, for he was the bearer of truths that revealed the Athenians had been deceived in their love. Hatred arises when a truth reveals the core belief about who we take ourselves to be is wrong.

Similarly, hatred arises when the “truths” of an established religion are shown false. Jesus preached against the claims of a religion that had become legalistic. He openly healed a blind man and cured another man of dropsy on the Sabbath. When the Pharisees rebuked him for allowing his disciples to pick grain on the Sabbath, Jesus said to them, “The Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath.”[13] Unlike the religious leaders of his day, Jesus, ignoring ethnicity and social status, associated with outcasts, beggars, lepers, and tax collectors. Fearing that growing support for Jesus among the common people, the chief priests and Pharisees called a council to deal with the threat Jesus posed to their authority. The council decided that “one man should die for the people, and not the whole nation should perish.”[14]

Dianoia and nous are not confined to doing mathematics and science but are fully present in any intellectual activity. Mozart, in a letter, describes how he composes music. He informs his correspondent that musical composition involves two elements: The musical parts are put together according to the rules of composition (dianoia); and the joy the composer receives when he sees the composition as a whole, much as the eye sees a beautiful landscape (nous).

Mozart: “When I feel well and in good humor, or when I am taking a drive or walking after a good meal, or in a night when I cannot sleep, thoughts crowd into my mind as easily as you could wish. Where do they come from? I do not know, and I have nothing to do with it. Those which please me I keep in my head and hum them; at least others have told me that I do so. Once I have my theme, another melody comes linking itself with the first one in accordance with the needs of the composition as a whole; the counterpoint, the parts for each instrument and all the melodic fragments at last produce the complete work. Then my soul is on fire with inspiration. The work grows; I keep expanding it, conceiving more and more clearly until I have the entire composition finished in my head although it may be long. Then my mind seizes it, as a glance of my eye would a beautiful picture or a handsome youth. It does not come to me successively, with various parts worked out in detail, as they will later on, but it is in its entirety that my imagination lets me hear it.”[15]

Those poets in Modernity who explore the depths of the interior life acknowledge publicly that all artistic creation rests upon gifts. The Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz, in the autobiographical essay “Catholic Education,” confessed, “I felt very strongly that nothing depended on my will, that everything I might accomplish in life would not be won by my own efforts but given as a gift.”[16]

Theodore Roethke in “On ‘Identity’,” a lecture delivered at Northwestern University, told how at the age of forty-four he was in a particular hell for a poet, a longish dry period; he thought he was finished. For weeks at the University of Washington, he had been teaching the five-beat line to aspiring poets but felt a total fraud because he could write nothing himself. “Suddenly, in the early evening, the poem ‘The Dance’[17] started, and finished itself in a very short time—say thirty minutes, maybe in the greater part of an hour, it was all done. I felt, I knew, I had hit it. I walked around, and I wept; and I knelt down—I always do after I’ve written what I know is a good piece.” The gift arrived and Roethke thanked the source, and “wept for joy.”[18]

We must not be misled into thinking that nous only operates in geniuses, giving them a direct grasp of profound truths. When a student of Euclid’s Elements truly grasps a demonstration, he or she shouts with joy, “I see it.” Through nous, the student, in a flash, immediately grasped the whole of the argument. Without nous, any rational argument cannot be apprehended. In other tutorials, scientific, poetic, and philosophic insights occur. A student may suddenly grasp how the Iliad forms an integral whole, or why Socrates in the Phaedo, on the day of his execution, spins philosophical “tales” about the immorality of the soul to comfort his distraught friends.

Every great work of art, every profound philosophical treatise, every deep scientific truth rests upon nous, upon the light bulb going off.

Spiritual Light

The Patristic Fathers realized that a person participates in the infinite through nous, the faculty of supernatural vision. Unlike dianoia, nous, as Plato and Aristotle showed, does not function by formulating abstract concepts and then arguing from them to a conclusion by means of deductive reasoning. Nous knows truth through immediate, direct apprehension.

For Plato, Aristotle, and the Patristic Fathers, the apex of human life is contemplation (theoria, in Greek), the perception or vision by nous through which a person attains spiritual knowledge. Depending on the depth of a person’s spiritual growth and development, contemplation has two main stages: It may be either the direct grasping of the first principles and the inner essences of natural things or, at its higher stage, an experience of God that is simultaneously aware that in His essence God transcends contemplation. St. Theognostos defines spiritual knowledge as the “unerring apperception of God and of divine realities.”[19]

St. Maximos the Confessor points out that contemplation is impossible without Divine Light: “Just as it is impossible for the eye to perceive sensible objects without the light of the sun, so the human intellect [nous] cannot engage in spiritual contemplation without the light of the Spirit. For physical light naturally illuminates the senses so that they may perceive physical bodies; while spiritual light illumines the intellect [nous] so that can engage in contemplation and thus grasp what lies beyond the senses.”[20]

Note that the word nous has different a meaning in the Western and Eastern Churches, which can be a source of unending confusion. In 1 Corinthians 14:15, St. Paul says, “I will pray with my spirit (pneuma), but I will pray with my mind (nous) also.” But the Eastern Fathers say, “I will pray with my spirit (nous), but I will pray with my mind (dianoia) also.” In the Eastern Church, nous and dianoia correspond to pneuma and nous in the Western Church.[21]

Even though practice of the moral virtues is an indispensable prerequisite for contemplation, experiencing contemplation itself is a gift from “above” that cannot be produced by any amount of human effort. “A soul can never attain the knowledge of God unless God Himself in His condescension takes hold of it and raises it up to Himself,” St. Maximos explains. “For the human intellect lacks the power to ascend and to participate in divine illumination, unless God Himself draws it up—in so far as this is possible for the human intellect—illumines it with rays of Divine Light.”[22] St. Hesychios the Priest adds that Divine Light “reveals itself to the pure intellect [nous] in the measure to which the intellect is purged of all concepts.”[23] To be without concepts, the mind must be stilled, so it rests from all thoughts.

Nous dwells at the innermost depths of a person’s being, at the spiritual center of every person’s life. This center is often called the “heart,” the place where the true self is discovered when the mysterious union between the divine and the human is consummated. Nous is sometimes called “the eye of the heart” to emphasize that it is the faculty of supernatural vision.

In the traditional Christian view, the purpose of a person’s life is deification, not proper moral behavior to assure entry into Heaven. In one sentence, St. Maximos gives the heart of Christianity: “God made us so that we might become ‘partakers of the divine nature’ (2 Peter 1:4) and sharers in His eternity, and so that we might come to be like Him (cf. 1 John 3:2) through deification by grace.”[24]

To become deified, the powers of ignorance and darkness must be overcome, so that a person can be fully aware of the spiritual principle (nous) within him or her, a principle obscured by the Fall. The human being is the greatest mystery in the entire cosmos because nous is the image of God, and to know nous is in some way to know God. The Patristic Father Nikitas Stithatos elaborates: “Since our intellect [nous] is an image of God, it is true to itself when it remains among things that are properly its own and does not divagate from its own dignity and nature. Hence it loves to dwell among things proximate to God, and seeks to unite itself with Him, from whom it had its origin, by whom it is activated, and toward whom it ascends.”[25] Nous allows a human person, through contemplation, to participate in Divine Life. “When the intellect [nous] has been perfected,” St. John of Damaskos teaches, “it unites wholly with God and is illumined by Divine Light, and the most hidden mysteries are revealed to it.”[26] Whether a person contemplates created things or God Himself, he becomes what he contemplates, and in this way becomes deified.

In every wisdom tradition, “There is a Light that shines beyond all things on earth, beyond us all, beyond the heaven . . . this is the Light that shines in our heart,”[27] and thus the human person is understood to be part divine and part human. For example, Hui-neng, the Sixth Patriarch of Zen in China, taught, “If you wish to seek the Buddha, you ought to see into your own Nature; for this Nature is the Buddha himself.”[28] The Sixth Patriarch also taught that unless the Zen disciple directly grasps his Nature, thinking of the Buddha, reciting sutras, observing fasts, and keeping the precepts will not bring him closer to the Buddha. The avowed object of all Zen discipline is not the proper performance of certain rituals, but “seeing into one’s Nature,” the most significant phrase ever coined in Zen Buddhism, according to D. T. Suzuki, the great commentator on Zen.[29] When the Zen disciple sees the inwardness of himself and natural objects, there is enlightenment, or satori.

Suzuki draws attention to the similarity between satori and solving a difficult mathematical problem. As we saw, Poincaré, Gauss, Hoyle, and innumerable other mathematicians and theoretical physicists report the experience of struggling with a seemingly intractable problem, when suddenly a solution is seen, followed by shouts of “Eureka! Eureka!” Such illumination of a mathematical problem is sudden, concise, and certain. But solving a mathematical problem does not cause an upheaval in a person’s entire life.

The Zen student too struggles, often desperately, with his problem, “seeing into his Nature.” The master always gives the disciple a koan, a special problem designed to be unanswerable through discursive thinking and with the customary understanding of the self. Master Kuei-shan, for instance, asked Hsiang-yen, a brilliant and quick-witted student, to describe his state before he was born of his parents. The koan plunged Hsiang-yen’s mind into a deep fog; his exceptional analytical power and logical acumen failed to arrive at an answer. He feverishly searched his books for something appropriate to tell the Master but found nothing. In utter despair, Hsiang-yen concluded he was not destined for enlightenment and burned all his books. Weeping, he left his master and vowed to devote himself to the meritorious work of maintaining the grave of the Sixth Patriarch of Chinese Zen, Hui-neng, as a shrine. Day in and day out, Hsiang-yen had no thought about the world, except for sweeping the ground. Then one day, sweeping away, he swept a pebble into a bamboo grove beside the shrine. The pebble struck a hollow bamboo and went “ping!” Hsiang-yen jumped up and down; he was suddenly awakened to his true self not born with his birth.[30]

As one Zen master said Satori comes, “When the bottom of the pail is broken through.”[31] Such a violent overturning of the ordinary understanding of oneself gives birth to a new person. At the moment of satori, the false self explodes and one’s true nature is seen; one’s individuality “becomes loosened somehow from its tightening grip and melts away into something indescribable, something which is of quite a different order” from what the Zen disciple was accustomed to.[32]

Satori and suddenly seeing the solution of a difficult mathematical problem are alike in that neither is a result reached by reasoning. Unlike mathematical knowledge, the noetic insights of satori cannot be expressed coherently or logically. Said in Western terms, mathematical insight entails both nous and dianoia, while satori lies entirely within nous. Suzuki confirms that the “knowledge contained in satori is concerned with something universal and at the same time with the individual aspect of existence. Satori is the knowledge of an individual object and also that of Reality which is, if I may say so, at the back of it.”[33] Zen masters acknowledge a sense of beyond when they describe the experience of satori as their own but feel it rooted elsewhere.

Living with the Light

For us Westerners, ideas are paramount, for we are people of the book. Except for mystics, such as Plato, Plotinus, Hildegard of Bingen, Meister Eckart, and Thomas Merton, the goal of Western philosophers and theologians has been to find the right ideas. For instance, Thomas Aquinas, in his masterpiece, Summa Theologica, gave convincing arguments for a Creator, the immortality of the soul, and eternal salvation.

However, Thomas Aquinas, the most rational and articulate of theologians, shortly before his death, had a mystical experience when celebrating the Mass, and as a result, he left the Summa Theologica unfinished. When urged by Reginald of Peperino to explain the radical change in his religious perspective, Thomas simply said, “Everything I have written seems like straw by comparison to what I have seen and now what has been revealed to me.”[34]

Father Raymond Braga, a Romanian Orthodox Priest, speaks of his road to God following both the Summa Theologica and the Philokalia, a collection of texts written by spiritual masters of the mystical Hesychast tradition. Interred in a Communist prison for eleven years, he confesses that before his solitary confinement, “I was a priest, I was a monk, and I’m ashamed to say that God, my God, was the God of the Book. But God is alive, is experience, is personal experience.”[35] Father Braga implicitly tells us that merely reciting the Creed in church, reading the Scriptures, and performing the correct rituals, many of which are cultural, does not make the interior life flourish or draw a believer closer to God; the idea of God often replaces the experience of God.

Thomas Aquinas and Father Braga do not speak of their new life that resulted from encountering Divine Light. Assuming such experience is universal, we can draw upon the Eastern Indian Tradition. The Yoga Vasistha, a syncretic work dating from the tenth century AD, describes the jivanmukta, the liberated man or woman living with the Light in this world. “Pleasures do not delight him; pains do not distress. . . . Although externally engaged in worldly actions, he has no attachment in his mind to any object whatsoever. . . . Outwardly he is very busy, but at heart very calm and quiet. . . . He rests unagitated in the Supreme Bliss. He does not work to get anything for himself. He is always happy, and never hangs his joy on anything else.”[36] In short, the jivanmukta is a new person; instead of a selfish seeker of her own happiness, she seeks the happiness of all around her, and in this way scatters joy and life.

Most of us are nowhere near being a jivanmukta, so what do ham-and-eggers like you and me do to fulfill our desire for spiritual perfection and genuine freedom? First, we cannot remain voluntary ignorant that all existence results from light. Our biological life rests upon light from the Sun; our inner life rests upon Divine Light.

Second, when we tell others who we are, we tell our life story, what has made us who we are and what we hope to become. Our idea of our self is a narrative about our successes and failures, our hopes and fears, our joys and sorrows, a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end. Our self-narrative rests upon intellectual light and pales to nothingness when we encounter Divine Light.

Third, we must acknowledge that an inner light is in every person. Every person we meet in ordinary, daily affairs—the mailman, the bank teller, the butcher at Whole Foods, the obnoxious teenager down the street with his blaring boom box—are part human and part divine, a storytelling self, often confused, dislikable, and in pain, but always transient, and a mysterious self, deathless, an image of God, worthy of unconditional love.

Endnotes

[1] Aristotle, Metaphysics, trans. W. D. Ross, in The Basic Works of Aristotle, ed. Richard McKeon (New York: Random House, 1941), I. 980a21, p. 689.

[2] Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis, (New York: Scribner’s, 1994), p. 24.

[3] Erwin Schrödinger, What is Life? with Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 153.

[4] C. F. von Weizsäcker, The History of Nature, trans. Fred D. Wieck (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949), pp. 142‑43. Italics in the original.

[5] What is true for seeing is true of the other senses: Physical and chemical changes in the brain are insufficient to explain any sensory perception. The sensible qualities a person perceives never appear in the brain as such. The brain itself is shrouded in complete silence, even while a person hears the deafening roar of a jet aircraft engine. Our brains do not become colder when we touch snow or harder when we touch iron. Not a single sugar molecule passes from the chocolate candy in the mouth to the gustatory region of the cerebral cortex—and yet we perceive sweetness notwithstanding. The brain tissue itself takes on none of the sourness of a tasted lemon or the acrid odor of the skunk’s spray that we smell.

Here is a short amusing example of why our interior life does not result from brain function alone. During the day, adenosine builds up in the brain to register the amount of time that has elapsed since a person awoke. When adenosine concentration peaks, a person feels the irresistible urge to sleep. The concentration of adenosine and the feeling of sleepiness are incommensurable. No matter how much a neuroscientist probes the brain with scans and chemical assays, she will never find sleepiness.

[6] V. S. Ramachandran, The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Quest for What Makes Us Human (New York: Norton, 2011), p. 248.

[7] Ibid., p. 249. Ramachandran’s definition of qualia is on page 248 and is incorporated in this quotation.

[8] Henri Poincaré, Science and Method, trans. Francis Maitland (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2003), p. 53.

[9] Ibid., pp. 53-54. Italics added.

[10] Karl Friedrich Gauss, quoted by Jacques Hadamard, The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949), p. 15.

[11] Fred Hoyle, “The Universe: Past and Present Reflections,” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 20 (1982): 24, 25. Available http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/527/2/Hoyle.pdf.

[12] Poincaré, Science and Method, p. 55.

[13] Mark 2:27. RSV

[14] John 11:50. RSV

[15] Mozart, quoted by Hadamard, The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field, p. 16.

[16] Czeslaw Milosz, “Catholic Education,” in Native Realm: A Search for Self-Definition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), p. 87.

[17] For ‘The Dance’ read by Tom Bedlam, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wKaoXy2KaJU.

[18] Theodore Roethke, On the Poet and His Craft, ed. Ralph J. Mills, Jr. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1966), pp. 223-24.

[19] Theognostos, On the Practice of the Virtues, Contemplation, and the Priesthood in The Philokalia, Vol. II, trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber & Faber, 1981), p. 365.

[20] Maximos the Confessor, Fourth Century of Various Texts, The Philokalia, Vol. II, trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber & Faber, 1981), p. 239.

[21] See John Romanides, Patristic Theology (Walla Walla, WA: Uncut Mountain Press, 2008), pp. 19-20.

[22] Maximos the Confessor, First Century on Theology in The Philokalia, Vol. II, p. 120.

[23] Hesychios the Priest, On Watchfulness and Holiness in The Philokalia, Vol. I, p. 177.

[24] Maximos the Confessor, First Century of Various Texts, in The Philokalia, Vol. II, p. 173.

[25] Nikitas Stithatos, On Spiritual Knowledge, Love, and the Perfection of Living: One Hundred Texts, in The Philokalia, Vol. IV, trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber & Faber, 1981), p. 143.

[26] John of Damaskos, A Discourse on Abba Philimon in The Philokalia, Vol. II, p. 355.

[27] Chandogya Upanishad, in The Upanishads, trans. Juan Mascaró (London: Penguin Books, 1965), 3.13.7.

[28] Hui-neng, quoted by D. T. Suzuki, Zen Buddhism: Selected Writings of D. T. Suzuki, ed. William Barrett (New York: Doubleday, 1996), p. 87.

[29] Suzuki, p. 74.

[30] See Toshihiko Izutsu, Toward a Philosophy of Zen Buddhism (Boston: Shambhala, 2001), p. 201.

[31] Quoted by Suzuki, p. 85.

[32] Suzuki, p. 105.

[33] Suzuki, p. 104.

[34]Thomas Aquinas, quoted by Bernhard Lang, Sacred Games: A History of Christian Worship (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), p. 323.

[35] Raymond Braga, Interview, John Paul II: The Millennial Pope, produced and directed by Helen Whitney, PBS Video.

[36] Yoga Vasistha, quoted by B.L. Atreya, “Indian Culture: Its Spiritual, Moral, and Social Aspects,” in Interrelations of Cultures, Their Contribution to International Understanding (New York: Unesco, 1953), p. 144.