|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

Charles Darwin’s On The Origin of Species was published in 1859, and evangelical Christians have yet to come to terms with evolution, since from a scientific perspective the Adam and Eve narrative in Genesis cannot be literally true. Albert Mohler, President of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, says the Adam and Eve story goes to the heart of Christianity: “When Adam sinned, he sinned for us. And it’s that very sinfulness that sets up our understanding of our need for a savior.”[1]

When asked if all humans descended from Adam and Eve, Dennis Venema, a biologist at Trinity Western University, affiliated with the Evangelical Free Church of Canada, replied: “That would be against all the genomic evidence that we’ve assembled over the last 20 years, so not likely at all.”[2] Like all evolutionary biologists, Venema argues that human beings cannot be traced back to a single couple given the genetic variation of people today; scientists cannot get the population size of humans below 10,000 people at any time in evolutionary history.

Almost all of us, scientists and laypersons alike, have so absorbed the rationalism of the eighteenth century, the mechanism of the nineteenth, and the materialism of the twentieth, that we unhesitatingly accept the many ways that science has rewritten the book of Genesis. The most direct way to see this rewrite is to examine the two classic works that laid out the principles of modern science, Copernicus’ book On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, published in 1543, and Francis Bacon’s, The Great Instauration, little more than a pamphlet, printed in 1620.

Ancient Astronomers Were Lovers of Divine Beauty

Before Copernicus, the understanding of the cosmos was based on direct observation. The stars move differently than terrestrial objects. The stars trace out circles around an imaginary axis that goes through the North Star and the Earth; a rock held up in the air and released falls in a straight line toward the center of the Earth. From such common experience, Aristotle drew an obvious, although incorrect, conclusion: The cosmos is composed of two kinds of matter, celestial and terrestrial. The celestial matter of the stars is eternal, moves in perfect circles, and is either divine or moved by something divine. In contrast, the Earth is composed of ever-changing matter whose natural movement is in a straight line toward the center of the Earth.

In the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic cosmos, the Earth is the basement, the sinkhole where all the gross, dull matter is concentrated. A half a century before the publication of Copernicus’ On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (1543), Renaissance philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola described the dwelling place of Earth as “the excrementary and filthy parts of the lower world.”[3] Inhabitants of the cosmic sinkhole suffered floods, earthquakes, and plagues while the angels and saints in heaven blissfully contemplated God. Even a quarter of a century after On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres appeared in print, the great French essayist Michel de Montaigne said people feel and see themselves “lodged here amid the mire and dung of the world, nailed and riveted to the worst, the deadest, and the most stagnant part of the universe, on the lowest story of the house, and the farthest from the vault of heaven.”[4] Contrary to the Copernican myth, the place of the Earth in a geocentric cosmos is not preeminent, nor does it lead to human pride or naïve self-love, unless the bubonic plague is preferable to eternal bliss.

Following Aristotle, Ptolemy begins his great work on astronomy, the Almagest (circa 150 AD), by first laying out in broad outline the three categories of knowledge — physics, mathematics, and theology. “In the highest reaches of the universe, completely separated from perceptible reality,” is an invisible and motionless deity, who is the “first cause of the first motion of the universe.”[5] The first cause, or Prime Mover, is the most intelligible entity that exists. Never-changing, the Prime Mover is unknowable to us because of its remoteness. Properly speaking, theology should be called guesswork, not a science, since the invisible and motionless deity is remote and thus unknowable.

Physics, the opposite of theology, investigates what is perceptible and near at hand. Terrestrial matter, unfortunately, is unstable and obscure, for such qualities as white, hot, sweet, and soft never remain. What is closest to us is least intelligible and thus, on the whole, unknowable. Like theology, physics is guesswork, but for a different reason; terrestrial matter is essentially unknowable. Consequently, philosophers can have no hope of agreeing about either the Prime Mover or terrestrial matter.

Only mathematicians using the indisputable methods of arithmetic and geometry have arrived at sure and unshakeable knowledge because mathematics occupies a middle ground between theology and physics. Numbers and geometrical figures are close at hand yet unchanging. While the stars are ever-moving around the Earth, they are eternal and unchanging in themselves. Astronomy partakes of both the physical, for the stars are perceptible, and the theological, for the stars are heavenly and divine. Because of their remoteness, however, the astronomer’s knowledge of the stars is limited.

The bulk of the Almagest is taken up with giving accounts of the irregular motion of the Sun and the wandering stars (planets). Careful observations show that the motions of the Sun and the planets around the Earth vary throughout the year, which poses a problem to Aristotle and Ptolemy since all celestial bodies were thought to move in perfect circles and never change in speed around their respective centers of motion.

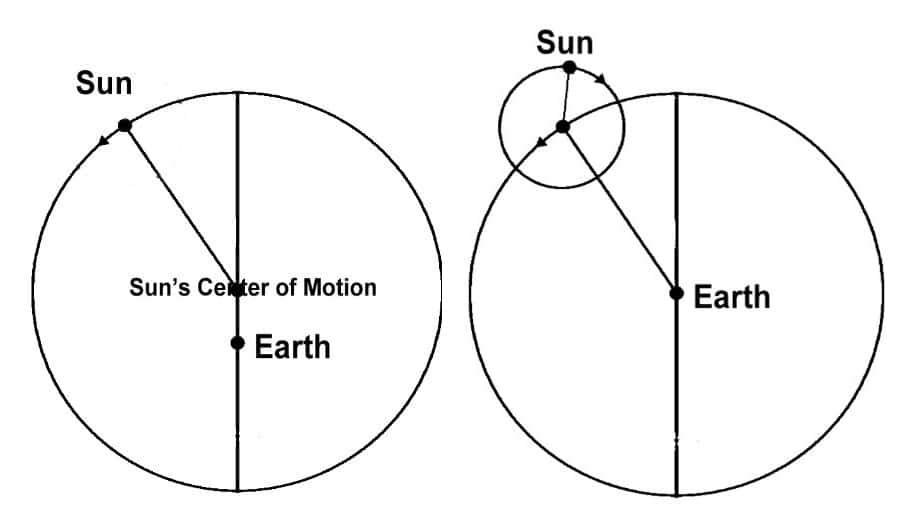

Ptolemy constructs two hypotheses to account for the observed irregular motion of the Sun in terms of regular circular motion, but he offers neither as the way the Sun really moves, see drawings. In the eccentric circle hypothesis, the Sun’s regular motion is not centered on the Earth. In the other hypothesis, the Sun rides on a small circle, called an epicycle; the regular motion of the epicycle is on the large circle, called the deferent that is centered on the Earth. The regular motion of the Sun is about the center of the epicycle. Both hypotheses account for the observed annual motion of the Sun about the Earth. Ptolemy offers neither hypothesis as an explanation of the Sun’s motion; each hypothesis is a likely story; the ancient astronomers had no way of choosing one over the other. A modern reader looking at these drawings may make the error of thinking that these are models of the Sun’s motion, which they definitely are not; they are mathematical artifices, accounts, likely stories, nothing more.

Ptolemy’s drawings are not representations of the motion of the Sun and the planets. If we define a map as a representation of an object or a process, then the figures in the Almagest are not maps.

Like all ancient philosophers, mathematicians, and astronomers, Ptolemy highlights how his discipline affects the whole person. The practice of astronomy results in persons of ethical action and good character: “From the constancy, order, symmetry and calm which are associated with the divine, it makes [astronomy’s] followers lovers of this divine beauty, accustoming them and reforming their natures, as it were, to a similar spiritual state.”[6]

How the Modern Scientist Displaced God

Copernicus begins astronomy where Aristotle and Ptolemy could not, with the book of Genesis. From Revelation, Copernicus concludes that the cosmos was fashioned by “the Best and Most Orderly Workman of all.”[7] Consequently, the cosmos must be intelligible and beautiful. Copernicus’ main critique of Ptolemy and his followers is that they did not discover the chief point of astronomy, the beautiful form of the cosmos. The geocentric cosmos lacks unity, and the parts are not harmonious. Copernicus likens a Ptolemaic astronomer to an artist taking hands, feet, head, and limbs from his different drawings of humans, each part beautifully drawn, and assembling them together; the result is a monster, since no two parts match. From Genesis, Copernicus concludes that the Ptolemaic cosmos must be wrong.

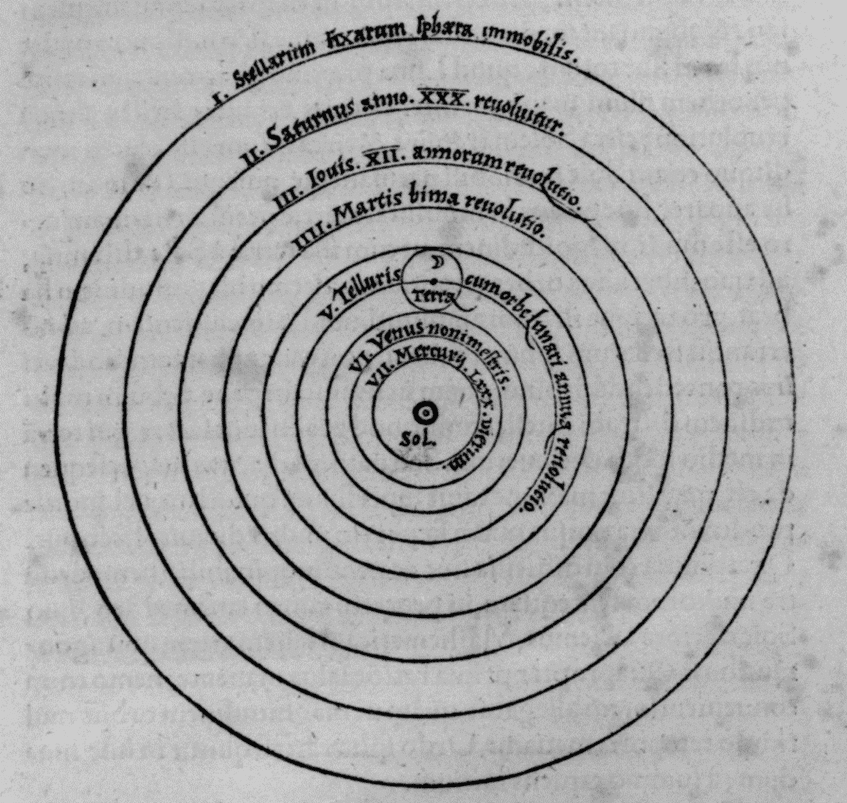

In Book One of On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (1543), Copernicus hurries to persuade the reader of the truth of the heliocentric cosmos, he offers as overwhelming proof the harmony and proportion of such a universe when seen from the outside, from a divine perspective, see illustration. Looked at from the outside, from God’s vantage point, the cosmos is seen to have a wonderful harmony and simplicity. The astronomer sees the truth of the heliocentric cosmos by simply looking at it. Copernicus exclaims, “How exceedingly fine is the godlike work of the Best and Greatest Artist!”[8]

Unlike Ptolemy, Copernicus draws maps of the cosmos. The astronomer sees that in a heliocentric cosmos, the Earth is a planet, a wandering star: “The center of the Earth too traverses that great orbital circle among the other wandering stars in an annual revolution around the Sun.”[9] No longer are the stars remote; we are riding on one in our annual traverse around the Sun!

From God’s vantage point, we see that the Aristotelian division of matter into celestial and terrestrial is wrong. The Earth is a wandering star, so either the Earth is divine or the stars are mundane like the Earth. The Earth, clearly, is mundane; thus the stars must be too. In the Copernican cosmos, the planets and the Earth move in perfect circles. Somehow the mundane matter of the Earth must have regular mathematical properties and thus must be intelligible. Furthermore, the intelligible stars can be known to us. Star-stuff and Earth-stuff are the same; we can study star-stuff by going out in the backyard and digging up earth. No longer must the scientists be satisfied with accounts, with likely stories; for now, they can grasp reality and explain how things really are.

The Copernican Revolution opened the entire cosmos to human understanding. In principle, scientists can grasp the whole show. Now, that is a boost to human pride! Copernicus gave the astronomer the vantage point of God; transported outside the universe to bear witness to its mathematical regularity, the astronomer, and later all scientists, became godlike. In the modern world, the scientist in his mind is a detached observer outside the universe, looking at the machinery of the world, contemplating the causes of things. No longer is the astronomer an inhabitant of an unknowable Earth surrounded by the great mystery of the divine stars. Far from demoting humankind, as Freud and others claimed, the Copernican Revolution elevated the scientist above the stars, planets, and Earth to a position of the highest being in the cosmos.

We now fast forward 260 years to Pierre-Simon Laplace’s visit to Napoleon Bonaparte at his country estate in 1802. The mathematician entertained the French political leader by relating the nebular hypothesis, Laplace’s scientific explanation of how the solar system formed from the rotating atmosphere of the primitive Sun. When Napoleon asked Laplace about the place of the Creator in his mechanical account of the origin of the solar system, he replied, “Sire, I have no need of that hypothesis.”[10]

If the universe is deterministic, as depicted by Newtonian physics, then a mathematician or a physicist approximates an all-seeing, super-computing god. A mathematician or a physicist, marooned inside his skull contemplating the Newtonian map, believes that he borders on the super-human, for he can calculate the future and the past of the universe.

Experimental Science: A Return to the Garden of Eden

Unlike Eve eating fruit from the forbidden tree, the beginning of the Second Fall can be precisely dated: In October 1620, Francis Bacon, the principal architect of the experimental method of modern science,published The Great Instauration. The word “instauration,” once a common English word, now sounds as if it belongs in a dreary Latin grammar book — instauro, instaurare, instauravi, instauratus. The Bing Dictionary gives an excellent definition of instauration: “the restoring of something that has lapsed or fallen into decay.”[11]

Bacon argued that what had fallen into decay was human knowledge. In the Garden of Eden, Adam named the animals according to their nature, and this knowledge gave Adam command over nature. “The state of knowledge is not prosperous nor greatly advancing,” Bacon lamented and declared, “a way must be opened for human understanding entirely different from any hitherto known.”[12] The main impediment to the advancement of knowledge was Aristotelian philosophy filled with “specious and flattering” propositions that gave rise to “contentious and barking disputation.”[13]

Aristotle’s principal error was his complete confidence in the senses, an error that became the medieval tag, “Nihil est in intellectu quod non sit prius in sensu.” (Nothing is in the intellect that was not first in the senses.) But for Bacon, “it is certain that the senses deceive.”[14] After the Fall, our intellects became clouded, and we became too attached to the senses. Furthermore, Copernicus demonstrated that our senses give “false information;”[15] the Earth rotates around its north-south axis and traverses an orbit about the Sun, while the senses report the Earth is stationary. The geocentric cosmos resulted from Aristotle and Ptolemy trusting the senses to report the way things truly are.

To partially restore mankind to the Garden of Eden, the only time in human history that man had real authority over nature, a new science was needed “in order that the mind may exercise over the nature of things the authority which properly belongs to it.”[16]

Bacon was the first to enunciate the fundamental principle of modern science: “The testimony and information of the sense has reference always to man, not to the universe; and it is a great error to assert that the sense is the measure of things.”[17] But a total rejection of the senses is madness, so to arrive at trustworthy information about nature, the senses must be assigned a limited role. In one sentence, Bacon presented the heart of the experimental method, something completely new to mankind: “The office of the sense shall be only to judge of the experiment, and the experiment itself shall judge of the thing.”[18] Said another way, the scientist touches the experiment, and the experiment touches nature. The scientist has no direct contact with nature. No scientist has ever seen, or will ever see, with his or her own eyes a neutrino, the helical structure of DNA, or the background radiation left over from the Big Bang. Scientific instruments touch nature, and the physicist, the chemist, or the biologist reads the numerical outputs, analyzes the data, applies theories, and eventually discovers the real constituents of nature — subatomic particles, molecules, and genes.

Bacon introduced one other principle entirely new to mankind: The true test of human knowledge is whether nature can be commanded, for “those twin objects, human knowledge and human power, do really meet in one; and it is from ignorance of causes that operation fails.”[19] While the goal of the new science is to “command nature in action,” the goal of Aristotelian philosophy was “to overcome an opponent in argument.”[20] Bacon tossed Aristotle on the trash heap of history, for implicit in Aristotelian physics is that terrestrial matter is obscure and barely knowable and thus cannot be commanded.

The new science would make mankind the master and possessor of nature, much as Adam was in the Garden of Eden, a time when “man was immortal and able to meet God face to face.”[21] Assuming the Genesis story is consonant with other myths of Paradise, we can speculate that Adam was “happy, and did not have to work for his food: Either a Tree provided him with subsistence, or the agricultural implements worked for him of themselves, like automata.”[22]

Bacon delivered two admonitions to his successors about the use of the new experimental method. First, he admonished scientists that the study of no part of nature is forbidden; “for it was not the pure and uncorrupted natural knowledge whereby Adam gave names to the creatures according to their propriety, which gave occasion to the Fall.”[23] In their pursuit of the truth, scientists have a divine mandate to ignore religious dogmas, philosophical doctrines, and cultural taboos. In effect, Bacon sanctioned the separation of science from religion and philosophy.

Second, Bacon addressed “one general admonition to all — that they consider what are the true ends of knowledge, and that they seek it not either for pleasure of the mind, or for contention, or for superiority to others, or for profit, or fame, or power, or any of these inferior things, but for the benefit and use of life, and that they perfect and govern it with charity.”[24] The general admonition exposes an inherent flaw in the Great Instauration. Bacon hoped to restore man to the Garden of Eden intellectually but knew man could not be restored morally.

In Bacon’s grand vision of the future of mankind, the command of nature will be given to morally corrupt men and women, simultaneously capable of great good and immense evil. In Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences, Galileo announces his monumental discovery that terrestrial matter does indeed obey mathematical laws, and consequently, the Earth and the stars are made of the same material. At the end of his treatise, Galileo applies his new knowledge discovered through the experimental method to the improvement of artillery. So much for Bacon’s general admonition. In the twentieth and the twenty-first centuries, laboratories worked for the benefit of life and the destruction of humanity, producing polio vaccine and thermonuclear weapons, aids for life and instruments of death.

In effect, Bacon rewrote the Bible. The Old Testament told how Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden; the New Testament gave hope that what had been lost through disobedience to God would be restored at some point through faith in Jesus Christ. In the new version of Genesis, the restoration of the lost Paradise was expected to come about not through faith, but from the “great mass of inventions”[25] that would flow forth from the new experimental science that would give mankind the command over nature that Adam had in the first Garden of Eden. As a result, the descendants of the first man and woman could on their own return to Paradise, and in this way “subdue and overcome the necessities and miseries of humanity”[26] that resulted from the expulsion of Adam and Eve to East of Eden, where women painfully suffered childbirth and the cursed ground brought forth thistles and thorns.

Science: The Only Path to Truth

The great mass of inventions that flowed forth from the new science founded on experiment, not on the Aristotelian observation of nature, captivated peasants, shopkeepers, and intellectuals, alike. The number of significant inventions in sixteenth-century Europe was meager: the flush toilet, bottled beer, and the Mercator map projection. The century in which Newton died, the eighteenth, included inventions that would transform society, such as the Franklin stove, gaslighting, the Watt steam engine, the cotton gin, the flying shuttle, and smallpox vaccination.[27]

The great mass of inventions persuaded ordinary people that science was the only path to truth, and that was bad news for theologians, philosophers, and poets, for they could not command nature. Their prestige began a steady, irreversible decline. Today, no one looks to poetry or philosophy for poetic knowledge or philosophical insights into nature and human affairs, or to theology for killer arguments that demonstrate the existence of God. Science and technology paralyzed the vocal cords of philosophers, rendering them mute about the three big questions that every person asks in the course of their life: Where did I come from?, What am I doing here?, and, Where am I going?

The arts and the humanities are thought to deal with individual experiences, subjective opinions, and historical and cultural accidents, not universal truths. An essay written by six eminent professors of literature and published by the American Council of Learned Societies asserts that “all thought inevitably derives from particular standpoints, perspectives, and interests.”[28] The life of the mind for these humanists, then, cannot focus on the universality of human experience and must finally degenerate into an endless labyrinth of rhetoric about opinions and private interests.

Bacon’s vision of a new Garden of Eden drew a buoyant optimism from the New Testament, the positive emotion accompanying the belief in the dawning of a new age heralding a bright future, where all the current ills of human life — poverty, illness, and strife — would be overcome. The United States Democratic Review, in 1853, predicted that “within half a century, machinery will perform all work — automata will direct them. The only tasks of the human race will be to make love, study, and be happy.”[29]

The attempt to institute Paradise on Earth was a bold, hubristic project, totally new to mankind, and unwittingly a vast social experiment, arguably a failed one.

Science as the only path to truth led invariably to materialism. The toolbox of science is limited to air pressure, chemical changes, electrical impulses in nerves, brain cell activity, and other measurable properties of matter; the experimental method of science thus entails materialism.[30] Said in terms of modern reductionism, “the universe, including all aspects of human life, is the result of the interactions of little bits of matter.”[31] In addition, the amazing new inventions focused virtually everyone’s attention on the good life in this world, away from salvation, at the expense of intellectual and spiritual values, the usual definition of materialism. In this way, Bacon transformed Judeo-Christianity into a secular, materialistic philosophy, and no doubt he would be aghast, for he vigorously opposed atheism: “I had rather believe all the fables in the Golden Legend, and the Talmud, and the Alcoran [the Koran], than that this universal frame is without a mind.”[32] He maintained that atheism reduces man to a mere animal: “They that deny a God destroy man’s nobility; for certainly man is of kin to the beasts by his body; and, if he be not of kin to God by his spirit, he is a base and ignoble creature.”[33]

To be continued. Part Two: A Return to the Garden of Eden: An Insane Goal

Main image: Adam and Eve expelled from the Garden of Eden on a stained-glass window in the cathedral of Brussels, Belgium, courtesy of iStock.

Endnotes

[1] Albert Mohler, quoted by Barbara Bradley Hagerty, “Evangelicals Question The Existence Of Adam And Eve,” National Public Radio, August 9, 2011.

[2] Dennis Venema, quoted by Barbara Bradley Hagerty, ibid.

[3] Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Oration on the Dignity of Man,.

[4]Michel de Montaigne, “Apology for Raymond Sebond,” in The Complete Essays of Montaigne, trans. Donald M. Frame (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1958), p. 330.

[5]Ptolemy, Almagest, trans. G. J. Toomer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), pp. 35–36.

[6] Ibid., p. 37.

[7] Nicolaus Copernicus, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, trans. R. Catesby Taliaferro in Great Books of the Western World, (Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1939), vol. 16, p. 508.

[8] Ibid., p. 529.

[9]Ibid., p. 525.

[10] See Ronald L. Numbers, “Science without God: Natural Laws and Christian Beliefs” in When Science and Christianity Meet, ed. David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), p. 271.

[11] As far as I could determine, the Microsoft Bing Dictionary is out of print and is no longer available online.

[12] Francis Bacon, The New Organon and Related Writings (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1960 [1620]), p. 7.

[13] Ibid., p. 8.

[14] Ibid., p. 21.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid., pp. 3, 7. Italics added.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., p. 22.

[19] Ibid., p. 29.

[20]Ibid., p. 19.

[21] Mircea Eliade, Myths, Dreams, and Mysteries, trans. Philip Mairet (New York: Harper, 1960), p. 43.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Bacon, The New Organon, p. 15.

[24] Ibid.

[25]Ibid., p. 103.

[26] Ibid., p. 23.

[27] For a timeline of inventions, see http://theinventors.org/library/inventors/bl1700s.htm.

[28] George Levine et al., “Speaking for the Humanities,” American Council of Learned Societies Occasional Paper, No. 7 (1989): 10.

[29] “The Spirit of the Times,” The United States Democratic Review 33 (Issue 8, Sept. 1853): 261..

[30] For a detailed discussion, see George Stanciu, The Great Transformation: How Contemporary Science Harmonizes with the Spiritual Life, Ch. 9, Dumb Idea # 3: Materialism.

[31] H. Allen Orr, “Awaiting a New Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, 60, No. 2 (February 7, 2013).

[32] Francis Bacon, “Of Atheism” in Essays, Civil and Moral.

[33] Ibid. Note: The Golden Legend is a 13th century collection of saints’ lives.)