|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

My father, a Romanian gypsy born in a Transylvanian village and raised in a thatched-roofed house with dirt floors, began his journey through life shaped by the Orthodox Church, by a peasant life not much changed in fifteen hundred years, and by face-to-face communal relations, not the Nation-State. We Stancius come from a long line of chicken stealers, fortune tellers, tax evaders, and draft dodgers, a heritage that served my father well in an America that “opened a thousand new roads to fortune and gave any obscure adventurer the chance of wealth and power.”[1]

My father did not leave behind in Old Europe the lord of the manor, the village priest, and the educated magistrate to be oppressed by corporate bosses in the New World, to be a mindless cog in mass production. He worked at Pontiac Motors, scraped together enough money to start a business, repeatedly failed and started over, until he succeeded and was then never under the thumb of another person again. My father discovered that Americans are frightened to exercise the incredible freedom offered them by their society; they fear failure will ruin their chances for a good life.

We Stancius take our freedom seriously. In college, graduate school, and the workplace, I was always shocked to see how my colleagues attempted to ingratiate themselves with “people who mattered,” how the opinions and approval of others directed their lives. One friend of mine, an experimental physicist, would listen carefully at dinner parties, and then before leaving, would make a parting speech to impress the people who mattered. His speech had nothing to do with truth, was mere flattery, sometimes cleverly disguised, other times not. I, on the other hand, learned early in life that most people held contradictory opinions, probably because of conflicting desires. In conversation with people who mattered, I tried to bring out the basic contractions they held. In this way, I made no friends to advance my career — indeed, I never thought of myself as having a career; however, I told myself I was focused on the truth — which was true to some extent — but mainly I was attacking authority, the enemy I refused to obey or seek favor from. The idea of seeking favor from a person of authority sickened me.

In graduate school, my unshaven face, my castoff clothes, and my demeanor that broadcast “I don’t give a crap about your stupid, academic values” were direct affronts to how physics professors lived. Years later, I found out that one theoretical physicist in the department maintained that my presence as a graduate student meant that the field was going downhill; he was dismayed and vowed to others he would sink me. When I finished graduate school, although many faculty members thought I was bright and knew that I published my Ph.D. thesis in the prestigious Physical Review Letters, a rarity in our department that gave me fifteen minutes of fame; yet, no one would write me a letter of recommendation. I could not be trusted to reflect well upon my “mentors.”

After I left the University of Michigan with a brand-new Ph.D. in theoretical physics, I drove aimlessly around Europe for a year, searching for direction in life. I did not begin my journey through this world at Mt. Sinai with Moses, or in Galilee with Jesus, or in ancient Athens with Socrates. I started off life in the cultural milieu of democracy, science, Protestantism, and capitalism. In my twenties, I inhabited a postmodern world, defined by Hiroshima, the Gulag, and the Holocaust, the wreckage of Modernity that called into doubt the Nation-State, progress, science, and God. I lived in a world without maps, without signposts directing me to God and moral certitudes. While I was a graduate student, I would occasionally audit classes in philosophy and literature, where I learned, nuanced in different ways, that “all thought inevitably derives from particular standpoints, perspectives, and interests.”[2] Music, poetry, philosophy, religion, and ethics were mere expressions of personal opinions, individual perceptions, or particular cultural viewpoints.

In Florence, I walked on the cobblestone streets that Dante had, but in all honesty, the Divine Comedy did less for me than sauntering across the Ponte Vecchio and trying out my wretched Italian on vendors. At one point in my aimless travel around Europe, I was shocked to see the rolling French countryside around Verdun covered as far as my eye could see with over one hundred thousand little, whitewashed crosses bearing the simple inscription, “Mort pour la patrie.” Nearby the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial occupied a small part of the battlefield of the final offensive of World War I that cost the Americans 117,000 killed and wounded, the French 70,000, and the Germans 100,000.

In 2017, the hundredth anniversary of the entry of the United States into the Great War to end all wars went by without a celebration, or even national notice taken to commemorate those brave doughboys who died for their country and “to make the world safe for democracy.”

The war slogans faded from public memory as rapidly as the lyrics from George M. Cohen’s catchy, patriotic tune “Over There.” How many of the 2,000,000 doughboys marched off to war with fragments of Cohen’s jingle reverberating in their minds? “Hoist the flag and let her fly, Yankee Doodle do or die . . . Make your mother proud of you, and the old Red, White, and Blue . . . And we won’t come back till it’s over, over there.”

For the 116,516 Yanks who died in Europe, it was over, over there. English poet Wilfred Owen begged his countrymen not to continue to tell the ancient lie from the Roman poet Horace: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. (It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.) One week before the signing of the Armistice, Owen died in action crossing the Sambre-Oise Canal. On Armistice Day, while church bells were ringing out in celebration, his mother received the telegram informing her of her son’s death in France. Perhaps, it was too much to hope that the first two lines from Owen’s “Anthem for a Doomed Youth” would never be forgotten: “What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? Only the monstrous anger of the guns.”

World War I, now, ancient history, forgotten — no one remembers — or cares — why 9.7 million soldiers died fighting a war that resolved nothing and led in twenty years to Europe’s second attempt at collective suicide.

I gave up on my search for human meaning in Old Europe. On my return to the States, my best friend in graduate school suggested I apply for a postdoc at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

The Samuel Glasstone Lectures

In my second week at the Lab, I attended five days of lectures given by Scribbling Sam Glasstone, a physical chemist whose encyclopedic knowledge came from writing numerous physics and chemistry handbooks. He had edited The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, one of the two bibles weapons designers used. The other one was the Los Alamos Primer, written in 1943 by Robert Serber, a nuclear physicist and protégé of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory during the Manhattan Project. Off to one side of the stage, hidden in darkness, Glasstone droned on in his British accent about yellowcake, Tube Alloys, and the Manhattan Project.

Los Alamos was a boy’s dream: the most exclusive, secretive club in the history of humankind. We were hidden away behind barbed-wire fences. To go from one security area to another, a person had to show a badge to a guard. We didn’t have a secret handshake, but we did have our own vocabulary; nothing in weapons work was called by it correct name. A bomb was a “device” or “gadget;” the detonation of a nuclear weapon was a “shot;” Los Alamos Laboratory was “the Ranch” or “the Hill;” an implosive bomb was made with “ploot,” for plutonium, named after Pluto, the god of hell. A hundredth-millionth of a second was a “shake” — a shake of a lamb’s tail. The chemical energy of a quarter of a ton of high explosive was a “jerk.” The Hiroshima shot released sixty kilojerks.

The second day of Scribbling Sam’s lectures was taken up primarily with the showing of Army film footage of the Trinity test, in a remote desert of New Mexico, in 1945. On screen, hundreds of scientists and technicians moved equipment into shacks, bunkers, and onto steel towers. Everything had to be hauled across ninety miles of flat shrubland, called Jornada del Muerto — the Journey of the Dead — by the first Spanish adventurers who trekked across it.

The Trinity device, spherical and about five feet in diameter, was slowly hauled up a hundred-foot tower. Inside it were about twelve pounds of ploot, a sphere 3.62 inches in diameter, surrounded by several feet of high explosive. When the high explosive was triggered, it was supposed to symmetrically crush the sphere of plutonium and initiate an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction. No one knew if the gadget would work.

Fat Man went off without a hitch. The flash of light was so bright that it had no definite shape. Then, a bright yellow hemisphere — flat side down on the desert floor — appeared. An enormous ball of fire grew, and as it grew, it rolled and churned. Then, an ominous mushroom cloud glowed a brilliant purple.

When the muffled rumbling of the movie soundtrack died away, the film’s narrator explained, “The expansion of the ball of fire before striking the ground was almost symmetric. Contact with the ground was made at six-tenths of a millisecond. At about thirty milliseconds, the fireball had expanded to nine hundred and fifty feet in diameter. At three seconds, the fireball developed a stem that appeared twisted like a left-handed screw.” This last description was that of the formation of the mushroom cloud that later would become the symbol of nuclear nightmare. The camera remained motionless; the mushroom cloud rose and became elongated, and appeared to me as an exposed, diseased brain with a long stem. I thought this is a visual update of Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.

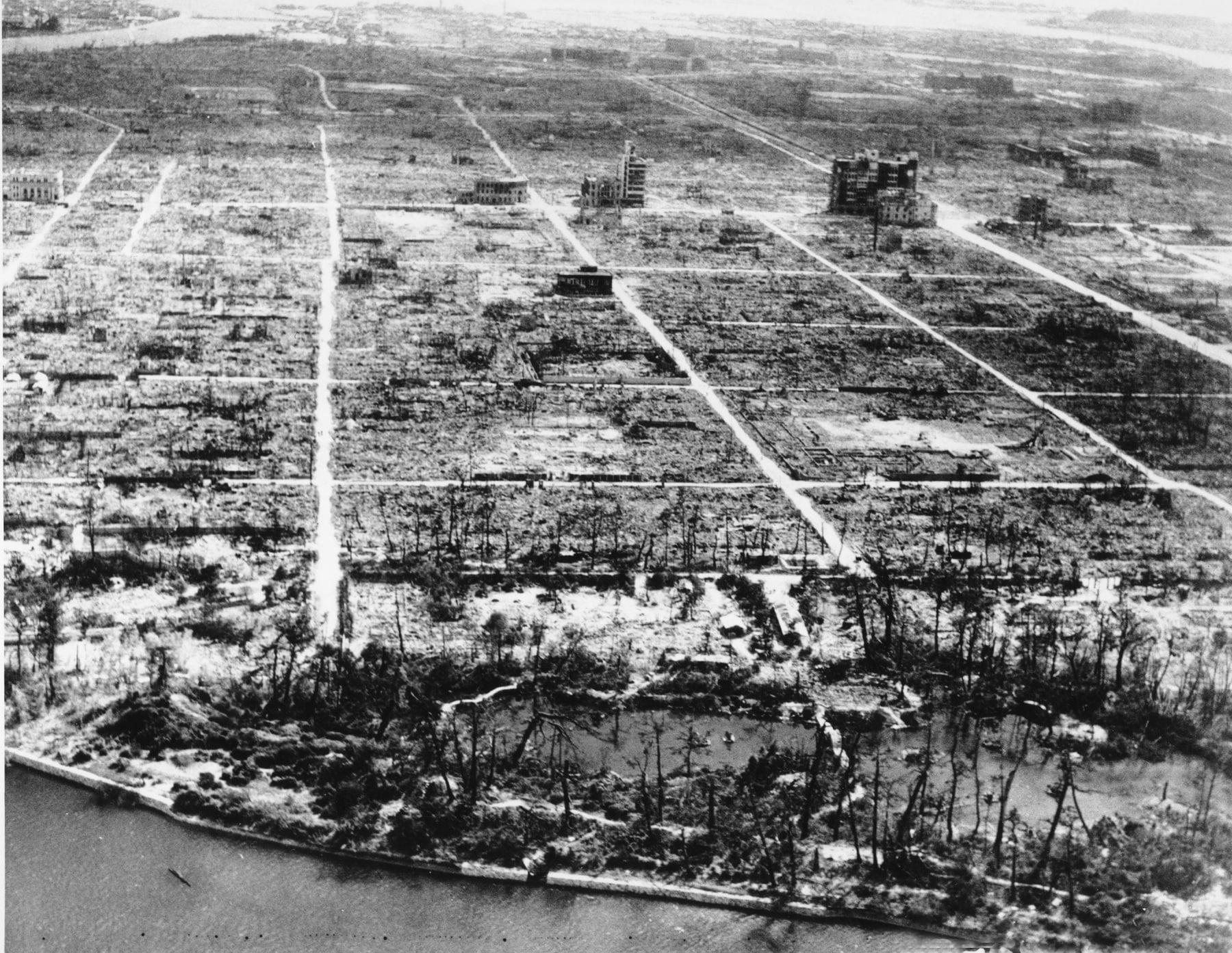

The film jumped ahead three weeks to Japan. Several Japanese cities had been spared from American conventional bombing in order that the full effect of nuclear weapons could be demonstrated. Little Boy, the code name of the uranium bomb, killed a hundred thousand persons and wounded another forty thousand. In nine seconds, Hiroshima was literally no more. (See Figure 1.) The photographs of the destruction were mind-boggling. The camera slowly panned across the destroyed city. My eye picked out several human skulls amidst the rubble, and I remembered the conversation I had with philosophy Professor Alfred Thayer when I was a freshman at the University of Michigan. He had told me, “The presence of an ethical symbol adds nothing to the factual content.”[3] Three days later Fat Boy killed at least forty-five thousand inhabitants of Nagasaki; the terrain and atmospheric conditions were less favorable than Hiroshima.

A month after the atomic bombing of Japan, Los Alamos scientists sifted through the rubble of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, studying the effects of nuclear weapons. Robert Serber appeared on the movie screen. Seated in a comfortable office, he recalled his scientific work in Hiroshima. With a nasal voice and a slight lisp, he said, “Everybody has defense mechanisms. Under stress of that kind, somehow, you get hardened to it in a couple days, no matter what you see. And, you manage to survive that way.”[4] He laughed self-consciously.

Serber held up a large gray square and explained, “It’s a piece of a schoolroom wall from a schoolhouse in Hiroshima, about half a mile from where the bomb went off. The flash burns are scarred by broken window glass. You can see the shadows of the window sash and the cord of the shade. From the angle from which this shadow was cast, we could measure the height at which the bomb went off. This was the evidence that it really went off at the height it was supposed to over Hiroshima.”[5]

Serber was delighted with his find. My heart sunk as I wondered whether the schoolchildren suffered flash burns, too.

Over the next three days, I watched movies of hundreds of shots at the Nevada test site and in the Pacific. I learned about the development of thermonuclear weapons and about other great advances in weapons technology. In the current nuclear weapons arsenal, thanks to Stan Ulam and Edward Teller, the co-inventors of the hydrogen bomb, there are gadgets a thousand times more powerful than those that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In his monotone, mechanical delivery, Glasstone cited the effects of a hypothetical detonation of a 1 megaton hydrogen bomb (the yield of 67 Hiroshima gadgets) over Detroit. “For a surface blast, there will be nothing recognizable remaining out to a distance of .6 miles from the epicenter. At 2.7 miles from the center of the blast, typical commercial and multi-story residential buildings will have walls completely blown away. Causalities will number 640,000.”[6]

On the projection screen in front of the darkened auditorium flashed a map of Detroit. The hypothetical detonation point selected was the intersection of I-75 and I-94, approximately at the civic center and about 3 miles from the Detroit-Windsor tunnel entrance.

Glasstone continued: “If one of the largest bombs in the Soviet arsenal — 25 megatons — were airburst over Detroit at 17,500 feet, almost all houses would be destroyed as well as most heavy industrial buildings and machinery. Such a blast would kill or severely injure approximately three-fourths of the citizens of Detroit. Recovery and rebuilding would be a very long-term, problematical issue.”

The projection screen went momentarily black. In the dark, I heard, “If the Cuban Missile Crisis had turned out badly, the thermonuclear war between the United States and Russia would have entailed the death of at least 100 million people in each country, the destruction of the industrial and military capacity of both, and long-term radioactive contamination of 50,000 square miles. Practically all surviving Russians and Americans would have suffered like Hiroshima survivors.”[7]

I didn’t need Scribbling Sam to tell me that if the nuclear strategy of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) had failed, then Los Alamos would have led to a catastrophe for humankind.

The invention of the hydrogen bomb by Ulam and Teller, described by Oppenheimer as “technically sweet,” is an instrument of genocide. Seated in the dark, I concluded if the United States ever uses such a weapon, the Nazis won World War II.

At the end of five days, I had no more heroes. Every one of my boyhood idols — the men I read about in physics textbooks, whose work I studied as a graduate student, and whom I dreamed of meeting someday — all of them worked at Los Alamos at one time or other; every one willingly committed himself, mind, heart, and soul, to the killing of other men. Einstein, of course, never traveled to Los Alamos. He wrote the letter to President Roosevelt that initiated the Manhattan Project.

The only two heroes of my boyhood not to appear at Los Alamos were the co-discoverers of quantum mechanics, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. Heisenberg, the second greatest physicist of the twentieth century, elected to stay in Germany and work for Herr Hitler. He devoted himself to the preservation of German culture, and to do this, he believed it necessary to become a member of the Uranverein, the “uranium club,” and to accept the position of chief theoretician of the German atomic bomb project. How had things gone so terribly wrong in the twentieth century? How could gifted, creative physicists take the beauty of quantum mechanics and turn it into Hiroshima? That would be like Mozart writing Don Giovanni to mollify the enslaved at Auschwitz.

Instead of working on military projects, Schrödinger chose self-imposed exile. He left Austria and spent the entire war in Ireland, a neutral country. At the Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies at Trinity College, he wrote the marvelous short book What is Life?. Schrödinger chose to understand life rather than to work to destroy it.

Glasstone’s lectures plunged me into the heart of darkness of the twentieth century. I was at a total loss about what to do. I was trained as a new barbarian to work for the scientific-industrial-military complex. The easiest path for me to follow was to help turn out new knowledge, products, or weapons, to enjoy my good salary, and not to think or to rock the boat.

Until I arrived at Los Alamos, I thought ethics was about regulating sexual conduct and not stealing; not exactly the most difficult topics to understand. Now the extremes that confronted me at Los Alamos forced me to face an issue that most persons go through life comfortably ignoring. In Buddhist terms, is creating television advertising aimed at children, or manufacturing junk food, or developing thermonuclear weapons right livelihood?

Mr. Akihiro Takahashi’s Story

The day the A-bomb dropped, I and other students of the Hiroshima Municipal Junior High School were on the athletic field.[8] We saw a B-29 approaching and about to fly over us. All of us were looking up at the sky, pointing out the aircraft. The blast came, and then the tremendous noise, and we were left in the dark. I couldn’t see anything at the moment of explosion. I was blown about ten meters. Everything collapsed for as far as I could see. I felt the city of Hiroshima had disappeared all of a sudden.

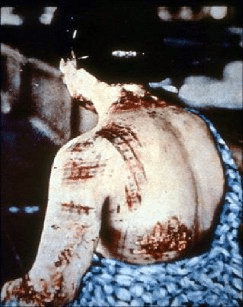

Then, I looked at myself and found my clothes had turned into rags due to the heat. I was burned at the back of the head, on my back, on both arms and both legs. My skin was peeling and hanging.

Automatically, I began to walk in the direction of my home. I walked toward the river and on the way saw many victims. I saw a man whose skin was completely peeled off the upper half of his body and a woman whose eyeballs were sticking out. Her whole body was bleeding. A mother and her baby were lying with the skin completely peeled off. (See Figure 2.)

I made a narrow escape from the fire. If I had been slower by even one second, the fire would have killed me. Fire was blowing into the sky, four or five meters high. A small wooden bridge had not been destroyed by the blast. I went over to the other side of the river using that bridge. On the other side, I purged myself into the water three times. The heat was tremendous, and I felt like my body was burning all over. For my burning body, the cold water of the river was a precious treasure.

When I arrived home, I found my grandfather’s brother and his wife. We have a proverb about meeting the Buddha in Hell. My encounter with my relatives at that time was just like that. To me, they seemed to be the Buddha wandering in the living hell.

The Golden Time

When I began a three-year postdoc at Los Alamos National Laboratory, one of the first persons I met was Jim Tuck, an English physicist and one of the principal designers of the conventional high explosive lenses of the plutonium bomb. After the war, he went back to England, but returned to Los Alamos, when invited to head Project Sherwood, the Laboratory’s initiative on controlled thermonuclear reactions, an impossibly difficult program that eventually was abandoned. Tuck modeled his laboratory after Los Alamos of the war years. Most physicists I know find Tuck vulgar and obnoxious. He is one of the last persons I would care to be marooned on a desert island with; nevertheless, I’ve always been willing to learn from anyone; I never let personal sentiments stand between me and the truth.

One day at lunch, Tuck and I were vying for the same empty table in the crowded cafeteria. He invited me to join him. Gaunt, almost emaciated, he towered a good six inches over me. His lunch consisted of a large salad with no dressing and a cup of tea. From his briefcase, he produced a small bottle of golden oil that he poured on his salad. Later, I learned Tuck always ate salads with only corn oil and a small amount of salt.

Tuck had just returned from France, and he proceeded to tell me in the most vulgar terms how French women on the Riviera wore bikinis to cover their private parts. I turned the conversation to the days of the Manhattan Project. After rambling for a while, Tuck told me, “Oppenheimer killed the idiotic notion prevalent in other laboratories that only a few insiders should know what the work is about and that everyone else should follow them blind. I, an almost unknown scientist, came here and found that I was expected to exchange ideas with men whom I had regarded as names in textbooks. It was a wonderful thing for me; it opened my eyes. Here at Los Alamos, I found a spirit of Athens, of Plato, of an ideal republic. I think that’s why the Manhattan Project scientists remember that golden time with enormous emotion.”[9]

Recently, I heard physicist Murray Peshkin express in a more colloquial way sentiments identical to those of Tuck. “In terms of day-to-day life, Los Alamos was a microcosm of the country, but intensified. By that I mean the following. War paradoxically can be a very happy time for those who are not at risk or who don’t have a loved one who is at risk. War is a time when everybody is needed, unemployment does not exist, when everybody has a role to play, and there is considerably camaraderie. Everybody has this goal to win the war. And so there were minor annoyances like rationing and stuff like that, but it was a time when people really felt good about themselves, and that was true even more so at Los Alamos. We were going to invent the weapon that would end this miserable war. And we did. Now, sixty years later, respected historians tell me that the war was within days of being ended even without that weapon and even without an invasion. But then it didn’t seem that way at all.”[10]

Oppenheimer described wartime Los Alamos as “a remarkable community, inspired by a high sense of mission, of duty and of destiny, coherent, dedicated, and remarkably selfless.”[11]

Many old-timers at the Laboratory, the living fossils from the Manhattan Project, told me with nostalgia in their voices of the golden time developing the first atomic bomb in the most unlikely of places, Los Alamos, New Mexico, located in an isolated, high desert of incredible beauty. Every physicist I knew at Los Alamos felt the allure — dare I say the spiritual attraction — of the New Mexico landscape.

Six months before I left the Laboratory, I met John Manley at a small dinner party. He was Oppenheimer’s right-hand man in planning and staffing the Laboratory. Manley and Oppenheimer could not have been more different. Oppenheimer was tall, with darting, blue eyes, and nervous energy. When he spoke, his long, thin hands were so contorted that his gestures seemed bizarre. Manley was short, easygoing, and exuded ordinariness, a friendly charm.

Manley and I ignored the other guests at the dinner party and spent the evening talking together. We both had gotten our degrees in physics from the University of Michigan; his Ph.D. was awarded three years before I was born. Manley kidded me that the University must have gone downhill since it now graduated the likes of me. We talked briefly about the golden era in Ann Arbor, the late twenties and early thirties, when Michigan’s summer school of physics was one of the international centers for research. Heisenberg, Fermi, Dirac, Teller, Ehrenfest, Oppenheimer, and many other physicists spent part of each summer in Ann Arbor trying to understand the full ramifications of the new quantum physics in an attempt to grasp the deep secrets of nature.

After World War II, Manley was one of the large number of scientists who left the Hill — the old-timers from the Manhattan Project always called Los Alamos the Hill or the Ranch — only to return several years later to perfect atomic weapons and to develop the hydrogen bomb. I asked Manley what drew him back to Los Alamos.

“I couldn’t find any place more to my liking,” he told me. “I love the climate, the small-town atmosphere, and the free spirit of inquiry at the lab.”

I did not let Manley’s soft-spoken charm beguile me. I knew he had not given me a straight answer, and furthermore, I knew he would not.

After two years, I pieced together what the old-timers told me. The development of the atomic bomb was an intense community effort, carried out under great hardship. Physicists, chemists, and mathematicians worked over sixty hours a week to build the first weapon of mass destruction. Only through the ardent dedication of all would the project succeed. Everyone — scientist, technician, secretary, and manual laborer alike — participated in a moral crusade of a cosmic order against an evil enemy. Modern war is not simply about soldiers, matériel, and the conquest of territory. War creates moral meaning and fellowship in a community striving for a lofty common end. I concluded that in Modernity, most persons are isolated individuals, who unbeknownst to themselves thirst for community and for a cause that transcends themselves.

A Moral Dilemma

At the fortieth anniversary of the founding of Los Alamos, Isidor Rabi, an experimental physicist and a close friend of Oppenheimer, called attention to the “greatness and folly of humanity,” in his commemorative talk, “How Well We Meant.”[12] In the war years, Los Alamos was “probably the greatest gathering of intellect of all times, with the possible exception of Athens in Ancient Greece.”[13] Scientists, then, believed that “only through science and its products could Western civilization be saved” from a “fanatic, barbarian culture.”[14] Rabi lamented that Americans have no historical perspective and in the postwar period “forgot the basic reason the United States entered the War . . . to protect civilization, and, in the process, save the United States.”[15] The folly that followed the greatness was that military power became an end in itself: “The question now is not so much how to protect civilization, but how to destroy another culture, how to destroy other human beings. We have lost sight of the basic tenets of all religions — that a human being is a wonderful thing. We talk as if humans were matter.”[16]

Inspired by Rabi’s wisdom, I made a distinction between making the atomic bomb and developing the hydrogen bomb. I, along with most Americans, was willing to accept that the morality of making the atomic bomb was a complex issue that most likely could not be resolved to the satisfaction of moral philosophers; yet, I vowed not to forget Rabi’s insightful title, “How Well We Meant,” which summed up the attitude of the majority of Manhattan Project scientists whom I had met.

When I was a postdoc at Los Alamos, dissenting voices about the development of nuclear weapons were absent both inside and outside the Laboratory. I heard at lunch Stan Ulam, the co-inventor of the hydrogen bomb and the smartest man I ever met, deliver to a table of postdocs an ethical argument for developing nuclear weapons. He argued, “I feel that one should not initiate projects leading to possibly horrible ends. But once such possibilities exist, is it not better to examine whether or not they are real? An even greater conceit is to assume that if you yourself won’t work on it, it can’t be done at all. I sincerely feel it is safer to keep these matters in the hands of scientists and people who are accustomed to objective judgments rather than in those of demagogues or jingoists, or even well-meaning but technically uninformed politicians.”[17]

I thought, “What a joke! As if scientists had any control over nuclear weapons once they were developed.” I asked myself, “Is this the best justification of his legacy to humanity that the smartest man I’ve ever met has to offer?”

I knew Stan Ulam was not above dissembling and playing to an audience. The moral justification for the Manhattan Project was Nazi Germany and ended on V-E Day, May 8, 1945. By then, however, the development of the atomic bomb had a momentum of its own and was out of the control of the scientists who worked on the project. By Trinity, the code name for the test shot of the first atomic bomb in New Mexico on July 16, 1945, the scientific-military-governmental bureaucracy was unstoppable, and the atomic bombing of Japan was inevitable. Four hours after Trinity, the heavy cruiser Indianapolis sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge and out to sea with the gun assembly of Little Boy.[18] August 6, 1945, Little Boy was dropped, and Hiroshima was destroyed in nine seconds. Three days later, Fat Man, a plutonium weapon, reduced Nagasaki to rubble.

I knew that many reporters pointed to the large number of churches in Los Alamos for such a small population as a sign of a hidden collective guilt. But many Los Alamos citizens, including a surprising number of atheists, go to church out of sheer boredom. In the Los Alamos Monitor, I read an excerpt of a sermon preached by the local Episcopal priest: “I make a bomb. The fact that I make a bomb does not mean it’s going to be used. I make a bomb, and it has the potential for evil as well as the potential for good. There is sin in the world. A human being cannot touch anything without the potential for sinfulness to be attached to it. The job of the Christian is to minimize the amount of evil in the world and the amount of sin. One of the ways to overcome evil actions is to fight against evil. Someone who intends to enslave people is evil. Duty requires the Christian to do what is necessary to prevent that evil act. That might require that I build a bomb like he has. That’s the rationale. Those are the moral principles.”

Even for me, a gypsy with no religious ties at that time, the use of the Gospel of Love to justify nuclear weapons was a moral outrage. It showed how Christianity had become subservient to the political order, especially in Modernity. Many Americans believe that democracy is God’s Plan for humankind and that they have the moral imperative to further His Plan. I doubted that God, if he exists, is an American.

Russell Miller, a colleague in the Theoretical Division, told me that the Congress of the United States determines what weapons should be developed and that his duty as a citizen was to carry out the wishes of the American people as expressed by their elected representatives. Like most Americans employed by corporations, Russell had surrendered his moral agency to an institution. His job was to carry out orders, not question them, much as the underlings of the Nazi regime claimed they were only carrying out orders. When I heard his justification for working to make nuclear weapons smaller and more powerful, in my imagination, I saw him give a straight-arm salute and heard his heels click together and an enthusiastic, “Yes, Mein Fuhrer, we can do it.”

Connie Thorpe, a physics Ph.D. and a weapons designer, told me at a dinner party, “I’m basically selfish. If a nuclear war wiped out me, my husband, and my child, I wouldn’t really care about what happens to anybody else.” At least that was an argument, unlike Stan’s charade, the preacher’s nonsense, and Russell’s moral surrender to the Nation-State. Connie’s honesty was admirable, although her narrow self-interest was appalling. Implicit in what she told me was that except for herself, her husband, and her child, she did not really care what happens to anyone, either now or in the future. If a thermonuclear war happens, what are one billion deaths, more or less? I guessed that only the accident of birth brought Connie to Los Alamos. If she had been born in Russia, she would have been designing nuclear weapons for a different employer — the Presidium of the Soviet Union — but not living as high on the hog.

For me, a committed materialist and thoroughgoing nihilist then, I could not come up with a rational argument why I should not continue to be a new barbarian and live high on the hog, drinking Chateaux-bottled wines and smoking cigars smuggled in from Havana. I had no allegiance to the new god, the Nation-State, nor did I accept, as Connie Thorpe had, what American culture repeatedly tried to pound into my head — natural self-interest drives a person to acquire more and more. As a result, I did not have a moral system, map, philosophy, or worldview that could reliably direct me to choose one course of action over another.

A Mistaken Notion of Freedom

At that time, I genuinely thought I was the freest person in the world. I did not care what other people thought of me; I had no ambition; I refused to pursue fame and fortune; no person or institution could force me to do anything. Like most inheritors of the Holocaust, the Gulag, and Hiroshima, I believed all ethical positions were arbitrary social conventions or personal idiosyncrasies. I realized that if my freedom were perfect, then one course of action in life is no better than any other course. But that did not bother me. My freedom was paramount, and my idea of freedom led me to the logically inescapable conclusion that no action based on universal principles is possible.

I probably would have gone on forever believing this nonsense — no, living this nonsense — if it were not for Scribbling Sam’s lectures on the history of nuclear weapons. Hiroshima changed everything for me. Staring at the heart of darkness shook me to the core. My nihilism stemmed from materialism, the ancient philosophy that holds that every object as well as every act in the universe is matter, an aspect of matter, or produced by matter, or in its modern scientific version “the universe, including all aspects of human life, is the result of the interactions of little bits of matter.”[19] If materialism were true, then every decision would be a thoroughly mechanical process, “the outcome of which would be completely determined by the results of prior mechanical processes,”[20] and thus freedom would be an illusion and to debate about the ethics of developing nuclear weapons would be absurd. Under the regime of materialism, I, like you, am a thing, a “meat machine,”[21] not an agent, who can choose good over evil, and “the human race is just a chemical scum on a moderate-sized planet.”[22]

For the psalmist, “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of His hands.”[23] For me, I looked at the horror of nature as portrayed by materialistic science and rebelled. I am not a thing, and humanity is not a chemical scum. I have moral agency and can act not to violate the dignity of any person.

For the first time in my life, I grasped that my life was not mine alone, that what I choose to do would affect others, and that I was inextricably bound to others, even to all humanity. In the course of my crazy, zigzag life, I arrived at the place where John Donne had been four hundred years before me. “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. . . . any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”[24] And, I heard the bell toll for me.

My postdoc ended, and the Laboratory for the Destruction of Humanity offered me a lucrative position in the Theoretical Physics Division, with the proviso that I work quarter-time analyzing data from the Nevada Test Site. I walked away, bid the Laboratory adios, even though my gypsy heart told me to take the money and pretend to live a comfortable, middle-class life — three years in the heart of darkness was enough for me.

Endnotes

[1]Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Harper & Row, 1966 [1835, 1840]), p. 11.

[2] George Levine et al., Speaking for the Humanities, American Council of Learned Societies Occasional Paper, no. 7 (1989).

[3] See Alfred J. Ayer, Language, Truth and Logic (New York: Dover, 1952), p. 107.

[4]J. Robert Oppenheimer, interview, Day after Trinity, director Jon Else (Pyramid Film & Video, 1981), video.

[5] Ibid.

[6] To corroborate Glasstone’s numbers, see United States government document The Effects of Nuclear War, pp. 27-32, pp. 37-39, and pp. 94-100.

[7] With the end of the Cold War, nuclear weapons have faded from public consciousness. Yet, regional wars fought with atomic bombs could create a global catastrophe. Alan Robock and Owen Brian Toon, both climatologists, claim that “new analyses reveal that a conflict between India and Pakistan, for example, in which, 100 nuclear bombs were dropped on cities and industrial areas — only 0.4 percent of the world’s more than 25,000 — would produce enough smoke to cripple global agriculture. A regional war could cause widespread loss of life even in countries far away from the conflict.” (Alan Robock and Owen Brian Toon, “Local Nuclear War, Global Suffering,” Scientific American 302 (January 2010): 74, 76.) They estimate that from such a “limited” war 20 million people in the region could die from bomb blasts, fire, and radiation. In addition, a billion people worldwide with marginal food supplies could die of starvation because of the ensuing agricultural collapse.

Robock and Toon do not consider the scenario of a rogue, terrorist state, such as ISIS, that embodies an apocalyptic view of history ending with Armageddon, acquiring nuclear bombs through the political collapse of Pakistan.

[8] The text is a condensation of “Testimony of Akihiro Takahashi.”

[9] James Tuck, quoted by Nuel Pharr Davis, Lawrence and Oppenheimer (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968), p. 186.

[10] Murray Peshkin, “Voices of the Manhattan Project,” The New York Times (Oct. 28, 2018).

[11] J. Robert Oppenheimer, United States Atomic Energy Commission: In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer (1954), p. 14.

[12] I. I. Rabi, “How Well We Meant” in New Directions in Physics: The Los Alamos 40th Anniversary Volume, ed. N. Metropolis, D. M. Kerr, and Gian-Carlo Rota (Boston: Academic Press, 1987), p. 257.

[13] Preface to New Directions in Physics: The Los Alamos 40th Anniversary Volume, ed. N. Metropolis, D. M. Kerr, and Gian-Carlo Rota (Boston: Academic Press, 1987), p. 257.

[14] Rabi, p. 263.

[15] Ibid., pp. 263-264.

[16] Ibid., 264.

[17] S. M. Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician (New York: Scribner, 1976) p. 222.

[18] Four days after delivering to the Tinian Island air base the gun assembly for the atomic bomb to be used for the destruction of Hiroshima, the USS Indianapolis was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine and sank within twelve minutes, resulting in the greatest single loss of life at sea for the U.S. Navy; only 317 crewmembers survived out of 1,196. Approximately 300 sailors went down with the ship; with no life rafts and only life jackets, most crewmembers died of exposure, dehydration, saltwater poisoning, and shark attacks. Perhaps eighty sailors died from the most shark attacks ever on humans. Robert Shaw as Quint in the movie Jaws depicted himself as a survivor of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis and described in a horrifying monologue the massive shark attacks.

[19] H. Allen Orr, “Awaiting a New Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, 60, No. 2 (February 7, 2013).

[20] See Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen, For the law, neuroscience changes nothing and everything, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London B (2004) 359: 1780, 1781.

[21] The quotation “the brain happens to be a meat machine” is widely attributed to Marvin Minsky, although I could not find the phrase “meat machine” in any article or book written by him.

[22] Stephen Hawking, quoted by David Deutsch, The Fabric of Reality (New York: Viking, 1997), pp. 177-178.

[23] Psalm 19. NIV

[24] John Donne, Essays, Meditation XVII.