|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

To combat the aimlessness, boredom, and depression induced by The Covid-19 Experiment, the New York Times ran a series on the best movies, TV series, and video games to cure their readers of the social-distancing blues. Over half America is distracted, watching the seven episodes of Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem, and Madness and other streaming videos on Netflix, not considering that the currently forced solitude is an opportunity for meditation and reflection upon life and death.

All the good books listed below are from the responses to the unscientific questionnaire that I recently circulated. They have one thing in common, captured by Joseph Conrad in his Preface to The Nigger of the Narcissus: “My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel — it is, before all, to make you see. That — and no more, and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your deserts: encouragement, consolation, fear, charm — all you demand — and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask.”

Life-altering books make us see by offering a “glimpse of truth.”

Antoine de Saint Exupéry shows us in Wind, Sand, and Stars the golden fruit born of two peasants, a child Mozart, who in all likelihood will be shaped by the “stamping machine.” This child Mozart, when an adult, “will love shoddy music in the stench of night dives. This child Mozart is condemned.”

A terrible truth. We were all once child Mozarts; open to the world, we could see, and then the stamping machine made us blind. An education based on rewards and punishments made us see only the shallow, the quantifiable. We were taught to ignore the “glimpse of the truth” by dutifully answering such exam questions as

- Do the occasional undertones of sexism and racism weaken the book?

- Choose several examples of passages that you find especially striking and explain what contributes to their effect.

- Which features of the author’s writing style are the most impressive?

The questionnaire: What books were pivotal in your life, and why? Were some books instrumental in your early life and later seen as of no interest or even ridiculous? Did any movie have the same impact as one of your life-altering books? Note: The matter in quotation marks are reader comments, not mine.

A former colleague of mine made the perceptive observation that often good books are best read at a certain age; so, I will begin with the childhood books.

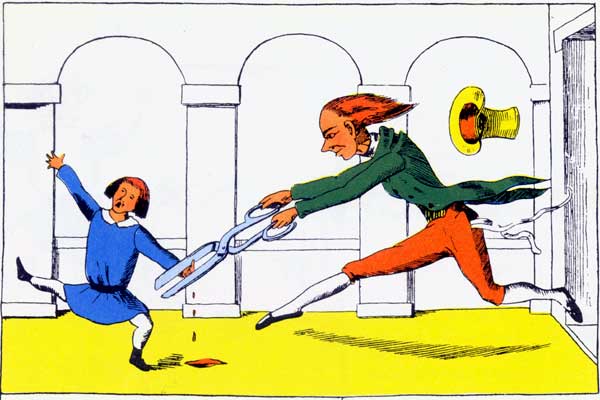

One reader pointed out that the Disney version of Pinocchio paled in comparison with the original by Carlo Collodi (1883). I can believe this; the Brothers Grim tales were purged of terror by Hans Christian Anderson and then sanitized by Disney. Struwwelpeter, once a Dutch classic picture book to instruct children to be good, which includes the story of how Little Suck-a-Thumb  had his thumbs cut off by the scissor-man.

had his thumbs cut off by the scissor-man.

No one mentioned Struwwelpeter as formative of their early childhood, but several readers told of their love of E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, and Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie series, books they returned to when they red them to their children.

Diary of Anne Frank: “is a coming of age book that was pivotal for me by being an honest view of the human person in terrible circumstances.”

The above reader also included A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith, My Seventeenth Summer by Maureen Daly, and Podkayne of Mars by Robert Heinlein. “I put these books together as the main topic was young love or first love. My family was very uncommunicative about falling in love and sex: it was the social tradition of emotionally restrained French Canadian culture combined with my maternal Grandfather having “a roving eye” and being unfaithful to my grandmother, though he remained married to her. The first two books, along with part of the Diary of Anne Frank, are written from the perspective of a young woman, were my introduction to a view of romantic love.”

Wind, Sand, and Stars by Antoine de Saint Exupéry was on most lists. One reader said, “Without exaggeration, his insights have shaped my own worldview and relationships profoundly. Above all, Exupéry helped me to begin to grasp, on the one hand, the radical connectedness of everything; on the other hand, the radical uniqueness of each human person — his or her own spirit. Each person has a unique spirit and a unique beauty particular to him or her (the Mozart) and yet we are all united in the One Spirit. We are not disconnected, isolated and self-contained individuals. Exupéry also challenged my tendency toward self-absorption and self-indulgence.” Several parents mentioned that in their childrearing, they were careful not to stamp out the Mozart in every child.

The Lord of the Rings Trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien: I think this was pivotal in my life because although it appealed to my love of fantasy and romanticism, it had an obvious depth. The characters were not thinly veiled morality plays. Characters had faults, struggles, and conflicting motives. Even the evil Orcs had ambitions, fears, and understandable motives. Frodo wishes that Bilbo or later Gandalf had killed Gollum, but Gandalf corrects him and says that Bilbo’s compassion for Gollum was his finest hour. Bilbo’s courage in facing the fear of going into the dragon’s lair, an event that happened when he was all alone in the tunnel, was his true heroic act. When I first read the book, it took about two days. I would read it while walking to school and every free hour.

The other book that was on most lists was Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl. “Through his personal experience of unimaginable and barbaric human suffering, Frankl offered to me profound insights about the meaning of life, the importance of love, the inner life, spiritual freedom, and humor. Three quotes of his have been foundational in my life: ‘The truth — that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire . . . . The salvation of man is through love and in love.’; ‘He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.’; and ‘It did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us.’”

The Bible was another near-universal: “without any exaggeration, the most pivotal book of my life. It has and continues to shape and form my heart, soul and mind, through and through. It provides the context and the principles upon which I understand, grasp, encounter, and relate to God, each human being, myself, and the world. In summary, as one who has been given the gift of faith, the Bible answers the two fundamental questions for me: How to be human, and how to love rightly.”

One reader reported that “the only life-changing book I ever read (at a very vulnerable age) was The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion by Sir James Frazer.

The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky. “I think that this book was pivotal in my appreciation of good and evil and the power of forgiveness. Alyosha as the ‘good’ boy and Grushenka as the ‘evil’ woman and how their roles temporarily flip was astounding. It was also the most powerful depiction of the illness of modern society with the depiction of Lise and her mother. Her mother loved humanity but could not stand the human persons closest to her.”

Anna Karenina by Tolstoy: “The greatest novel, ever.”

From one reader, who appears to have read everything, she modestly replied,

“Here are a few books that made a profound impression on me.

Thoreau’s Walden for love of and succor in nature, coupled with elegant writing.

Huck Finn, of course, for instilling independence, love of the open road, er, river, and rage against injustice.

Jane Eyre for illustrating the whole of a resourceful woman’s life. I first read Bronte when I picked up an abandoned copy in my high school’s halls at the end of a school year.

JD Salinger, because I think he wrote the story of my life — and he never even knew me, and I never lived in NYC. How’s that for writing?”

Two biographies and one autobiography were submitted.

Gandhi the Man: How One Man Changed Himself to Change the World by Eknath Easwaran.

Robert Kennedy and His Times by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.: “I’m sure this one is particular to me, but RFK, especially the man he became after his brother was assassinated, has been a personal hero of mine (hence my career as a lawyer and federal prosecutor).”

All the Strange Hours: The Excavation of a Life by Loren Eiseley. “Eisely’s autobiography conveys his struggle to acknowledge wonder in the age of Newtonian mechanism but also his moral character and the human part of science. (He became an anthropologist in part because of the good character of the anthropology professor.) Fitting for these times, Eiseley describes a childhood friend, “the rat,” who led the neighborhood boys and showed exemplary leadership, cleverness, and courage who suddenly disappeared, dead because of an infectious disease.

Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville: “As a post-modern, imbued with an exaggerated individualism, an unhealthy sense of autonomy, and an inherent distrust of authority, Tocqueville’s observations cut me to the core. As an American, I love my liberty, my autonomy, and my self-containment. I am a Cartesian through and through! Tocqueville’s observations about the American philosophy and approach to life challenged my worldview and cultural formation. Initially, his observations of America made me angry. In time, however, I came to realize the unnatural tendencies of American living. Tocqueville’s observations set me on a path toward authentic human living.”

Stanciu: On my first reading of Democracy in America, Tocqueville could have been sitting directly across from me, each of us with a snifter of Calvados, for he accurately described the way I encountered the world. Like all Americans, culture instilled in me a disposition to rebel against all authority. I have yet to meet an American — rich or poor, white or black, old or young — who does not smart under the thumb of another. I thought of myself as King of the Castle, deciding what is true and false, what is morally good and bad, what is beautiful and ugly. Pure democratic hubris!

Nature of the Universe by Fred Hoyle. “In high school, I took one only science class, and we only read one book, this one. Looking back, it had a huge influence on my life. I had never been interested in science until I read that book.”

Euclid’s Elements. Stanciu: The beauty of mathematics knocked me off my feet. I remember the first time I saw the demonstration that the prime numbers are infinite. My first thought was how could anyone ever prove that — and, then, right before my eyes, in a few bold strokes, the proposition was proved. I ran through the proof again and again, enjoying the unity, the elegant balance, and the surprise of the demonstration, much as I imagined a musician delights in the Mozart or the Bach that runs through his head.

For the first time in my life, I knew something. Before this, I thought knowledge was confined to particulars or the practical. I had no inkling that I could know anything beyond such things as “The American Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776” and “The carburetor is a device for mixing air with gasoline to produce a combustible mixture.” With mathematics, I entered a new universe. When I understood Euclid’s demonstration that the prime numbers are infinite, the 2,500 years that separated us vanished. Euclid and I were linked together; both of us transcended time in some mysterious way.

Here are the books listed without commentary.

Hamlet, King Lear, and Henry V by Shakespeare.

The Nichomachean Ethics by Aristotle.

Republic by Plato.

The Prince by Machiavelli.

City of God by Augustine.

Story of My Life by Helen Keller.

The New Organon by Francis Bacon.

Two items that were not books were listed.

“Seeing the play Our Town at a vulnerable age was a life-changing experience that forcibly confirmed my preoccupation with the transience of life and the sublime value of loving relationships when seen in retrospect.”

“When I was younger, Tchaikovsky, especially the Sixth Symphony, was an extremely important emotional release for me. I take this as a remedy to my upbringing that overly suppressed the expression of emotion. Listening years later, Tchaikovsky’s music did not have the same effect on me, and I can’t even describe the effect completely.”

The reason I asked about movies is that I have never seen a movie that has ever had a pivotal impact on me as any book. I am sure that I have seen a thousand movies, but I am like a child; movies are entertainment tonight. I thought this might be something quirky about me — I know that two of my former students, both highly intelligent and widely read, are nuts about movies — so, I wanted to see if anyone would report a life-changing movie. Since no one did, we should explore, at some point, how books, plays, and movies differ.

3 Responses

Fascinating list. How could I forgotten how good Loren Eiseley is?

What a great idea! I loved reading everyone’s choices and the reasons behind them. Thanks for doing this!

Both the Republic and Nicomachean Ethics revealed that my narrowly evangelical Christian ethics was not the only possibility. I was shocked, humiliated, and forever changed by just learning that complete advanced ethical systems existed before Christ was even born. I was never the same.