Modernity ends in the twenty-first century with the completion of the Dome that seals off its inhabitants from the transcendent, resulting in their imprisonment in a Nation-State, a consumer culture, and the imaginary worlds created by governments, corporations, and media.[1]

Far from sheltering them, the Dome prohibits Divine Light from entering their lives. Reality is the dead world of neutrinos, electrons, and quarks, life a manifestation of genes, and natural selection the only story. The inhabitants of the Dome hear that the history of life is the survival of the fittest, where Death is the final arbiter of who loses and who wins in the contest to leave the most genes for posterity. Modernity is completed: Matter is all, mind an epiphenomenon in a pointless universe; God is dead; the True, the Good, and the Beautiful are subjective opinions, without capitals. Matter rules; human beings its slaves; ethics and love illusions. Homo sapiens is merely another animal, more wretched than the other species because humans can see the dismalness of existence, yet the truth cannot set them free.[2]

Experiment

The construction of the Dome took four hundred years. In 1620, Francis Bacon in The New Organon: Or the True Directions Concerning the Interpretation of Nature set two anchors of the Dome’s foundation. The first anchor tethered modern science to experiment, not observation. “The office of the sense shall be only to judge of the experiment, and the experiment itself shall judge of the thing.”[3]

Said another way, the first anchor declares that the scientist touches the experiment, and the experiment touches nature. The experimenter has no direct contact with nature. No scientist has ever seen, or will ever see, with his or her own eyes an atom, the helical structure of DNA, or the background radiation left over from the Big Bang. Scientific instruments touch nature, and the physicist, the chemist, or the biologist reads the numerical outputs, analyzes the data, applies theories, and eventually discovers the real constituents of nature — subatomic particles, molecules, and genes. The Tevatron, for example, judges the top quark, and physicists judge the output of the Tevatron. (See Figure 1.)

The Screen

Dome dwellers touch the Screen, and the Screen touches the world; the Screen encompasses the touch screens of smartphones and laptops, the HD screens of digital TVs, the screens of digital cameras, even the big screens of multiplex cinemas.

Under the Dome, dwellers believe that their screens bring them the world. Carol Kaesuk Yoon in her review of the movie Avatar, the 3-D, five-hundred-million-dollar technological extravaganza, rejoices over the replacement of actual experience with the manufactured. Avatar “has recreated what is at the heart of biology: the naked, heart-stopping wonder of really seeing the living world.”[4] The trek through the local multiplex screen does not include sore feet, a parched throat, or insect bites, much less a pause in silence to hear the baritone squawks of ravens or to see the play of intense sunlight on the bark of a juniper tree.

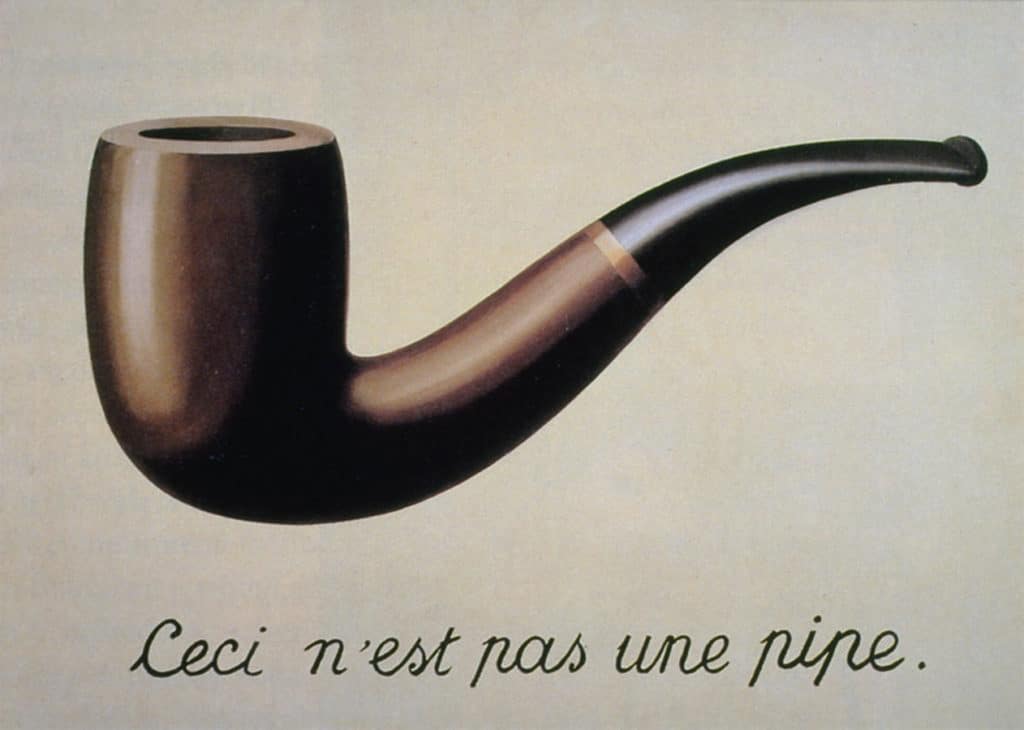

An opera, Gulf War II, or the Amazon rain forest seen on the Screen is taken for experience of the real event or place. But the hollow, depleted images bear little resemblance to reality, and not only because they are edited, rearranged, and altered. The viewer of a Screen-opera never feels the excitement that runs through an opera house just before the performance begins; the viewer of a Screen-war never is subjected to the confusion of battle or the incredible physical vibrations that accompany an artillery barrage; the viewer of a Screen-Amazon never smells the rotting organic matter of the jungle or hears the silence that pervades the deep recesses of the rain forest. Dome dwellers believe that the Screen is a video pipeline that brings the world to them, right into their living rooms, classrooms, subways, or coffee shops. An artificial, manufactured experience is taken for a genuine human experience. (See Figure 2.)

Science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick points out that Dome dwellers are trapped within multiple artificial worlds: They “live in a society in which spurious realities are manufactured by the media, by governments, by big corporations, by religious groups, by political groups — and the electronic hardware exists by which to deliver these pseudo-worlds right into the heads of the reader, the viewer, the listener.” Pseudo-realities manufactured by corporations unceasingly bombard Dome dwellers with “whole universes, universes of the mind.”[5]

Under the Dome, objects of nature are absent; images are reality; and isolated individuals wear ever-changing masks fabricated out of images created to sell products. The Screen isolates citizens from each other and nature, and as a result, the interior life collapses to hollow images and counterfeit emotions. Direct experience of nature, of society beyond the provincial, and of the operation of government are either nonexistent or considered of no value; everything is mediated through technology. The absence of direct experience unleashes the imagination, where anything can happen. As a result, under the Dome, conspiracy theories, speculations, and rumors dominate social media and much of what passes for news on cable TV.

Paradise on Earth

Bacon’s second anchor has two parts: 1) “Those twin objects, human knowledge and human power, do really meet in one;”[6] and 2) the “great mass of inventions”[7] that will flow forth from the new science will give man the command over nature that Adam had in the Garden of Eden, and thus humanity on its own can return to Paradise.

With Baconian optimism, the United States Democratic Review, in 1853, predicted that “within half a century, machinery will perform all work — automata will direct them. The only tasks of the human race will be to make love, study, and be happy.”[8]

Those twin objects of Bacon, human knowledge and human power, have produced staggering wealth, eradicated numerous diseases, eliminated famine, and reduced backbreaking labor to all but nonexistence. Although much of the wealth generated by science and technology has not been distributed justly, nevertheless, except for the relatively small numbers of homeless and destitute, Dome dwellers are incredibly wealthy by historical standards. Everyday, labor-saving machines, such as clothes washers, electric ovens, and gas-fired furnaces, are taken for granted, as is access to precious medical advances, such as genetically-engineered pharmaceuticals, laparoscopic surgery, and magnetic imaging devices.

Two hundred years of capitalism created for the wealthy and the poor a superabundance of goods. The typical Walmart Supercenter carries 142,000 different items. A shopper at Kroger’s or Whole Foods can buy blueberries in December grown in Chile, fresh flowers flown in from Columbia, and organic lamb imported from New Zealand.

Laptops, flat-screen TVs, and smartphones are everywhere, in the ghetto as well as aboard yachts, which is not to deny the scandal that three million children under the Dome live in abject poverty, the kind found in Bangladesh, one of the poorest countries in the world[9] or to discount the marked increase in midlife mortality of white, non-Hispanic Dome dwellers, the result of “deaths of despair” caused by drug addiction, alcoholism, and suicide in a declining middle class.[10]

The skewed income distribution under the Dome belies the more or less equal sharing of the enormous improvement in health and physical well-being as well as increased leisure time brought about by science and technology. In what past society did plumbers vacation in Cancún or petty clerks gamble in Las Vegas?

For many Dome dwellers, buying, owning, and consuming material goods are the essence of the good life. In this late stage of capitalism, products are therapy for the disenchanted soul; the right clothes, haircut, or smartphone means personal happiness, filling a void in the soul.

New inventions and technologies continually produce new goods and thus previously unknown desires, and as a result, Dome dwellers are placed on the treadmill of desiring more and more. The marketplace thus instills values: For “a general plenty”[11] to be consumed, an unlimited desire for material goods must be developed through advertising and mass media. In this way, everyone’s attention is focused on the good life in this world.

Capitalism aims to make dome dwellers feel good about themselves and pleased with their lives. Entertainment 24/7, new product launches, and celebrity gossip distract dweller from the reality of suffering, death, and from transcendent beauty and moral goodness, from those deep interior experiences that force a person to ask the three big questions: “Who am I?”; “What am I doing here?”; and “Where am I going?”

With this amazing wealth and advanced technology are Dome dwellers happy? Psychologist Daniel Kahneman and economist Angus Deaton analyzed the responses of more than 450,000 Dome inhabitants surveyed in 2008 and 2009 about their emotional well-being. Kahneman and Deaton focused on an “individual’s everyday experience — the frequency and intensity of experiences of joy, stress, sadness, anger, and affection that make one’s life pleasant or unpleasant.” They sought an answer to the question “does money buy happiness?” Not surprisingly, “low income exacerbates the emotional pain associated with such misfortunes as divorce, ill health, and being alone.” Unexpectedly, Kahneman and Deaton discovered that emotional well-being does not increase significantly beyond an annual household income of $75,000. “More money does not necessarily buy more happiness.”[12]

While advanced medical technology is making substantial progress in treating the physical diseases of Dome dwellers — cancer, atherosclerosis, and diabetes — the diseases of the interior life are taking over — alcohol and drug abuse, sex addiction, binge eating, and depression. A 2011 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that between 1988 and 2008 the rate of antidepressant use by all ages under the Dome increased nearly 400 percent; 11 percent of Dome dwellers aged 12 years and over now take antidepressant medication.[13]

Over the course of several hundred years, Dome dwellers freed themselves from the past, transformed nature into a commodity, centralized political power, and instituted bureaucracies, all with the aim of making themselves happy in this world. The superabundance of material goods and so little happiness under the Dome led to the widespread opinion that “we do not live by bread alone; we must have cake, too.”

Novelist and social observer James Baldwin claimed that Dome dwellers possess the “world’s highest standard of living and what is probably the world’s most bewildering empty way of life.”[14] Can anyone dispute that the way of life under the Dome has failed to make people happier? The entire Baconian project has been realized, except its end, Paradise, the happiness of humankind.

Individualism

René Descartes in Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences (1637) drove in the other two anchors to secure the Dome. His first anchor was an intellectual directive: Begin “with the simplest and most easily known objects in order to ascend little by little, step by step, to knowledge of the most complex.”[15]

Bacon had fuzzily formulated the remaining starting point of the new science: “what the sciences stand in need of is a form of induction which shall analyze experience and take it to pieces.”[16] With the clarity of a mathematician, Descartes promulgated the dictum that every whole is completely understandable in terms of its smallest parts and how they interact. Descartes’ method, now known as Cartesian reductionism, has two steps: First thoroughly understand the simplest parts, and then construct the whole as a sum of the parts.

The presumption of Dome scientists is that in resolving anything to its smallest parts they really get to know the thing because the smallest parts are what are most important, most causal, and most real. Since the smallest parts of anything are pieces of matter, an inescapable consequence of reductionism is that material particles are fundamental; everything else is a byproduct or an aftereffect. Reducing wholes to parts does not stop until everything in the universe, including our daily lives, is reduced to quarks and leptons, or perhaps infinitesimal vibrating strings or some presently unknown elements that future particle physicists will decide are the ultimate constituents of matter. In this way, reductionism inevitably leads to materialism. Dome scientists believe that “the universe, including all aspects of human life, is the result of the interactions of little bits of matter.”[17]

The great mass of inventions founded on modern science drew ordinary people to materialism. The flying shuttle, the Franklin stove, the Watt steam engine, the steamboat, bifocals, and the cotton gin instituted the other meaning of materialism, the devotion to material possessions and physical comfort at the expense of intellectual and spiritual values.

Under the Dome, Cartesian reductionism became an intellectual rage. The political organization under the Dome was established by John Locke, in England, and James Madison, in America. For Locke and Madison, the smallest units of society are isolated, autonomous individuals. They argued that in a state of nature, all men are “free, equal, and independent;” yet, each isolated individual is “constantly exposed to the invasions of others;” property is “very unsafe, very insecure;” and existence is “full of fears and continual dangers.”[18] Since no individual can rely upon the goodwill of others for the protection of his goods and life, individuals contract with each other to hand over their natural power to protect themselves and their property to the State. Self-interest, weakness, and natural enmity caused isolated individuals to form political societies.

Students and workers under the Dome compete for gold stars and promotions. Everyone is a real or potential competitor of everyone else; the losers on the economic battlefield are left alone to fend for themselves as best they can. Love is confined to the bedroom; marriages dissolve, children drift in a social vacuum, and friendships, primarily based on utility and pleasure, come and go. Each individual is narrowly shut up inside of himself. If Aristotle were alive today, he, no doubt, would predict that contemporary America would disintegrate, given nearly non-existent tradition, widespread disrespect for law, and friendship reduced to the private realm and weak at that.

Alexis de Tocqueville envisioned social life under the Dome: “I see an innumerable multitude of men, all equal and alike, constantly circling around in pursuit of the petty and banal pleasures with which they glut their souls. Each of them, withdrawn into himself, is almost unaware of the fate of the rest. Mankind, for him, consists in his children and his personal friends. As for the rest of his fellow citizens, they are near enough, but he does not notice them. He touches them but feels nothing. He exists in himself and for himself . . .”[19]

Loneliness

Under the Dome, loneliness is epidemic. One out of every four households consists of only one person. Roughly twenty percent of Dome dwellers feel so isolated from others that loneliness is a major source of unhappiness in their lives.[20] Loneliness, the desolate, empty feeling of being deprived of human companionship, is an inescapable consequence of individualism. Dome dwellers move away from their families, do not know their neighbors, and get accustomed to walking down the same crowded streets every day without looking anyone in the eye.

Inhabitants of the Dome always feel a vague sense of estrangement and loneliness, no matter where they are. Countless popular songs express the aching pain and empty feeling of social isolation. You feel more alone with more people around, Bob Dylan agonizes.[21] Where do all the lonely people come from? the Beatles ask.[22] Some Dome dwellers lament, “We’re more connected than ever through Facebook and Instagram, but we’re more apart.”

Many, if not most, Dome writers assume that aloneness is the human tragedy, the condition of humankind. Novelist Thomas Wolfe understood the intense loneliness of his life as universal: “The whole conviction of my life now rests upon the belief that loneliness, far from being a rare and curious phenomenon, peculiar to myself and to a few other solitary men, is the central and inevitable fact of human existence. When we examine the moments, acts, and statements of all kinds of people . . . we find, I think, that they are all suffering from the same thing. The final cause of their complaint is loneliness.”[23]

Vice Admiral Vivek H. Murthy, the Surgeon General of the United States from 2014 to 2017, observed that “loneliness and weak social connections are associated with a reduction in lifespan similar to that caused by smoking 15 cigarettes a day and even greater than that associated with obesity, [as well as with] a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, depression, and anxiety.”[24]

The depression caused by loneliness is a boon to the makers of Zoloft, Wellbutrin, and Prozac.

The Two Modes of the Mind: Dianoia and Nous

Descartes’ second anchor, also from the Discourse on Method, is “Reason is naturally equal in all men,”[25] which seems innocuous in our age of democratic equality. Descartes took the operation of Reason as defining, comparing, analyzing wholes into component parts, and drawing conclusions from first principles. Such discursive or step-by-step thinking the ancient Greek philosophers called dianoia. Descartes rejected nous, the capacity for effortless knowing. Unlike dianoia, nous does not function by formulating abstract concepts and then arguing from them to a conclusion through deductive reasoning. Nous knows truth by means of immediate, direct apprehension.

In the traditional Christian view, nous dwells at the innermost depths of a person’s being, at the spiritual center of every person’s life. This center is often called the “heart,” the place where the true self is discovered when the mysterious union between the divine and the human is consummated. Nous is sometimes called “the eye of the heart” to emphasize that it is the faculty of supernatural vision.

For the Church Fathers, the apex of human life is contemplation, the perception or vision by nous through which a person attains spiritual knowledge. Depending on the depth of a person’s spiritual growth and development, contemplation has two main stages: It may be either the direct grasping of the first principles and the inner essences of natural things or, at its higher stage, an experience of God that is simultaneously aware that in His essence God transcends contemplation. St. Theognostos defines spiritual knowledge as the “unerring apperception of God and of divine realities.”[26]

Under the Dome, nous is denied; the source of all knowledge is taken as unaided human effort and activity; a sudden insight is attributed to the unconscious mind.

The movement from Descartes’ rejection of nous to the pervasive nihilism under the Dome was inevitable. Without first principles that are grasped directly, philosophy and theology are reduced to futile entanglements of the discursive intellect, to verbal wrangling, and to endless hair-splitting with no issue. Dome philosopher Richard Rorty correctly argued that if “there is nothing deep down inside us except what we have put there ourselves,”[27] then Nietzsche’s view that truth is a “mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms”[28] follows. History and also reflection show that dianoia alone — like algebra — has no content, and if sense perception and even the results of scientific experiments be joined to dianoia, what results, at best, are “likely stories,”[29] not the certain knowledge that Bacon and Descartes sought. In the twenty-first century, atheists rejoice and believers despair that there is no acceptable proof for the existence of God. But without nous no compelling proof exists for anything.

The Coup de Grâce to Truth

Under the Dome, technology administered the coup de grâce to truth. The Internet is the first medium in history, besides the agora of ancient Athens and the town meetings in New England villages, to create many-to-many communication; the phone is one-to-one and books, radio, and television are one-to-many. In the Digital Age, “every time a new consumer joins this media landscape a new producer joins as well, because the same equipment — phones, computers — let you consume and produce. It’s as if, when you bought a book, they threw in the printing press for free.”[30] Smartphones, tablets, and laptops are cheap; consequently, the Screen is ubiquitous. In 2021, Facebook had 2.85 billion monthly active users worldwide[31]; the corresponding number for Twitter was 285 million.[32] Digital technology encourages every Dome dweller to be a reporter, a broadcaster, and a commentator.

In a world where digital technology is everywhere, professional journalists and public intellectuals no longer tell trusting citizens how to vote, what to believe about politicians, and what to think about social issues. Today, the talking heads are entertainers, necessarily voicing extreme and at times outrageous positions to get above the clutter, and not respected the way Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite were in the era of one-to-many broadcasting.

Social media allow hundreds of millions of Americans with the click of a mouse to disseminate their opinions without the scrutiny of grammarians, fact-checkers, and editors, the guardians of print culture. Anyone, anywhere, anytime, now, can instantly post an opinion on anything. The Internet has become an ocean of opinion, one comment washing over another, quickly submerging whatever truth that tries to surface. Intense emotions and personal opinions superseded rational argument and objective facts.

Life under the Dome is no Paradise. The post-truth society cannot rationally solve the enormous problems generated by technology and capitalism: climate change, a declining middle class, racial injustice, extreme materialism, and military adventurism. Since Dome dwellers cannot distinguish fact from fiction, political disaster awaits them.

The bad news is the good news: Cultural upheaval, political turmoil, and religious decline free more and more of us to easily step out from under the Dome.

How to Escape from The Dome

1. Give up the dream of Paradise on Earth. The sight of the rubble of Hiroshima killed the comforting narrative that the progress of science and technology leads to universal happiness; the sound of frozen corpses thrown on sledges in the Gulag destroyed the utopian story of humans instituting a perfect political order; the smell of burning bodies in Auschwitz annihilated Nietzsche’s myth that the ascendance of the Overman, the perfect race, will raise humankind to a new level of existence.

Bacon and Descartes imagined a glorious future for humans after we “make ourselves, as it were, the lords and masters of nature;”[33] however, the ever-ascending arc of science and technology turned out to be not under human control. Physicists, neuroscientists, and computer and genetic engineers are the new sorcerer’s apprentices, having summoned great forces that they now cannot either control or banish. Science and technology became the masters and possessors of us.

No one knows how molecular nanotechnology, genetic engineering, and artificial intelligence will transform human life, not the engineers at M.I.T., the geneticists at Stanford, or the computer scientists in Silicon Valley. Perhaps the ever-ascending arc of science and technology is headed to superintelligence, maybe to a thermonuclear war that annihilates humankind, or possibly to a severe climate change that destroys Homo sapiens and most other creatures.

2. Abandon the technology that mimics your spiritual nature. The Screen does not bring you the world, although you do have the capacity to be connected to all that is.[34] Of all the natural creatures, only humans can grasp a whole. Animals do not grasp what things are; as a result, their innate responses are keyed to a few external stimuli. A deaf turkey hen pecks all her own chicks to death as soon as they are hatched. A jackdaw, a medium-sized member of the crow family, will take a fluttering black cloth for another jackdaw. Chimpanzees perceive the shape, size, color, and design of stuffed toys, yet are frightened by such “drolly, unnatural”[35] things and cannot see they are harmless pieces of cloth and wood. The scientific study of animal perception demonstrates that an animal’s world is not the world we see at all but more closely resembles “a small, poorly furnished room.”[36]

To begin to realize your spiritual nature disconnect from the Screen and connect to the immediate physical world, to the taste of an excellent Burgundy, to the silence after a fresh snowfall, to the wonder and mystery of nature, to the perfection of Mozart’s Misericordias Domini (K. 222) that touches the transcendent.

3. Reject the truncation of love induced by capitalism. You are not a commodity or a profit-maximizing creature living a beggarly existence. Learn to give generously and to love without desiring a reward. Self-interested love directed to the acquisition of material goods ends with individual unhappiness and social catastrophe, as life under the Dome amply demonstrates. A life of service to others, not the attainment of wealth and status, is a genuinely human life.

To love without the desire for reward is how God loves everyone, including Dome Dwellers. If an isolated individual attempts to love the way God does, he will enter into genuine friendship with God, and eventually he will love his enemies and pray for those who persecute him, even though he can never be friends with them. God loves all persons, for “He makes His sun rise on the evil and the good, and sends rains on the just and on the unjust.”[37] By loving the way God does, Dome dwellers “become partakers of the divine nature.”[38] Many Church Fathers were fond of telling their brethren, “God became man, so man might become God.” The aim of human life is union with God and deification, not the acquisition of more and more material goods.

Even one Dome dweller who exhibits Jesus’ second great commandment — “You shall love your neighbor as yourself”[39] — begins to establish a true community that helps others escape from the Dome.

Endnotes

[1] Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis of Culture, trans. Alexander Dru (New York: Mentor, 1963), p. 73, introduced the “dome that encloses the bourgeois workaday world,” which we developed in our own way.

[2] Philosopher Michael Ruse asserts that the truth makes no one free; all we can do is accept that we are slaves of matter. See Michael Ruse, interview.

[3] Francis Bacon, The New Organon: Or the True Directions Concerning the Interpretation of Nature (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1960 [1620]), p. 22.

[4] Carol Kaesuk Yoon, Luminous 3-D Jungle Is a Biologist’s Dream. Italics added.

[5] Philip K. Dick, “How to Build A Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later,” in Philip K. Dick, I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon (New York: Doubleday, 1985).

[6] Bacon, p. 29.

[7]Ibid., p. 103.

[8] The Spirit of the Times,” The United States Democratic Review 33 (Issue 9, Sept 1853): 261.

[9] National Poverty Center, Extreme Poverty in the United States, 1996 to 2011.

[10] Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century.

[11] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations [1776]), Bk. I, Ch. I.

[12] Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (August 4, 2010) 107 (38): 16489–16493.

[13] NCHS Data Brief, Antidepressant Use in Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2005–2008.

[14] James Baldwin, “Mass Culture and the Creative Artist: Some Personal Notes,” Daedalus, 89, No. 2 (Spring 1960): 374.

[15]René Descartes, Discourse on Method (1637), trans. Robert Stoothoff, in John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, and Dugald Murdoch, The Philosophical Writings of Descartes Volume I, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), Part Two, p. 120.

[16] Bacon, p. 20.

[17] H. Allen Orr, “Awaiting a New Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, 60, No. 2 (February 7, 2013).

[18] John Locke, Second Treatise of Government, ed. C. B. Macpherson (New York: Hafner, 1980 [1690]), pp. 52, 66.

[19] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Harper & Row, 1966 [1835, 1840]), pp. 691-692. Italics added.

[20] See John Cacioppo and William Patrick, Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection (New York: Norton, 2009), p. 5.

[21] See Bob Dylan, “Marchin’ to the City,”on the album Tell Tale Signs: the Bootleg Series Vol. 8.

[22] See The Beatles, “Eleanor Rigby” on the album Revolver.

[23] Thomas Wolfe, “God’s Lonely Man” in Thomas Wolfe, The Hills Beyond (New York: Harper & Row, 1941), p. 186.

[24] Vivek H. Murthy, “Work and the Loneliness Epidemic,” Harvard Business Review (Sept. 27, 2017).

[25] Descartes, Discourse on Method, Part One, p. 111.

[26] Theognostos, On the Practice of the Virtues, Contemplation, and the Priesthood in The Philokalia,vol. II, trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber & Faber, 1981), p. 365.

[27] Richard Rorty, Introduction, Consequences of Pragmatism: Essays, 1972-1980.

[28] Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense,” p. 46.

[29] For a discussion of likely stories, see Peter Kalkavage, Introduction, Plato, Timaeus, trans. Peter Kalkavage, 2nd ed. (Indianapolis, IN: The Focus Philosophical Library, 2016).

[30] Clay Shirky, How Social Media Can Make History,” Ted Talk, 2009.

[31] Statista, Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide as of 1st quarter 2021 (in millions).

[32] Statista, Number of monthly active international Twitter users from 1st quarter 2029 (in millions).

[33] Descartes, Discourse on Method, Part Six, pp. 142-143.

[34] See George Stanciu, Wonder and Love: How Scientists Neglect God and Man.

[35] Wolfgang Kohler, The Mentality of Apes, trans. Ella Winter (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1931), pp. 320-321.

[36] Jacob von Uexküll, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, p. 85.

[37] Matthew 5:45. RSV

[38] 2 Peter 1:4. RSV

[39] Matthew 22:39. RSV