|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

17 The Mind/Body Connection

The ACE Study at Kaiser Permanente San Diego correlated current adult health status to childhood experiences decades earlier. The average age of 17,421 adults in the Study led by Vincent Felitti was 57, with almost half men and half women. The racial makeup was eighty percent White, ten percent Black, ten percent Asian, and slightly less than one percent American Indian. Seventy-four percent had attended college; everyone had high-end medical insurance. Clearly, a middle-class population. Robert Anda, the epidemiologist for the Study, observed, “It’s not just them; it’s us.”[1]

Because the average study participant was 57 years old, the Study measured the effect of childhood experiences on adult health status a half-century later. Furthermore, Felitti and his colleague monitored their large cohort of participants for at least five years. Given the statistics, the surprising results of the Study are indisputable.

The ACE Study is the most significant medical study in the second half of the twentieth century. Felitti correctly claimed that “the findings are important medically, socially, and economically: They provide remarkable insight into how we become what we are as individuals and as a nation.” Given the Study’s conclusions, modern Western medicine focuses on “tertiary consequences far downstream” from the source of many diseases.[2]

The Study considered ten categories of adverse childhood experiences that generally are kept as family secrets and hidden further by shame and social taboos. The ten categories were 1) recurrent humiliation; “you are the stupidest kid I’ve ever seen;” experienced by eleven percent of the participants in the Study 2) heavy-duty physical abuse; severe beatings with fists, sticks, or other objects; twenty-three percent 3) contact sexual abuse; twenty-eight percent for women and sixteen percent for men 4) major emotional neglect; fifteen percent 5) significant physical neglect; ten percent 6) growing up in a home where the mother was treated violently; eleven percent 7) someone in the home was an alcoholic or a user of street drugs; twenty-six percent 8) a family member was chronically depressed, suicidal, or in a state hospital; twelve percent; 9) not having biological parents present in the home; what was most devastating was maternal abandonment; twenty-four percent 10) one family member was imprisoned; five percent.

The researchers created an ACE score that tabulated not the number of events but the number of categories. In this obviously middle-class population, sixty-seven percent had an ACE score of one or higher; eleven percent, one in nine participants, had a score of five or higher. A key finding was that a person with an ACE score of six or higher had a shortened life expectancy of almost twenty years and was 22.2 times more likely to commit suicide than an individual with an ACE score of zero. An adult with an ACE score of four or higher had 1.9 times the odds of getting cancer and 2.2 more likely of having ischemic heart disease, the number one killer in the United States.[3]

The Ace Study established beyond dispute that regardless of income, race, or access to care, adverse childhood experiences are a risk factor for the most common serious diseases in America. Yet, the medical community ignored this landmark study published in 1998 probably because the Study applied to all of us, not just the marginalized, and because the study exposed the what, not the how. Felitti and his fellow researchers offered no explanation for how having an ACE score of four or more increased the chances of an individual fracturing a bone by 1.6 times and for developing diabetes by the same likelihood. No obvious connection exists between breaking bones and high blood sugar.

18 How the Body Responds to Adverse Childhood Experiences

Jacqueline Bruce and her fellow researchers suspected that adverse childhood experiences affected cortisol levels. The researchers compared the morning cortisol levels of 117 maltreated 3- to 6-year-olds residing in foster care with non-maltreated 3- to 6-year-olds living consistently with at least one biological parent. In this latter group, household income was less than $30,000, parental education was less than a 4-year college degree, and family did not have any previous involvement with child welfare services.[4]

In this study, published in 2009, severe physical neglect meant parental failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, or medical care; emotional maltreatment designated parental rejection, abandonment, or failure to protect children from witnessing traumatic events. The researchers discovered that “maltreated foster children showed significant alterations in their morning cortisol production compared to non-maltreated children. . . . The foster children with low morning cortisol levels had experienced more severe physical neglect, whereas the foster children with high morning cortisol levels had experienced more severe emotional maltreatment.”

Bruce and her colleagues suggested that a physically neglected child has chronic stress that decreases cortisol production; in contrast, an emotionally maltreated child is subjected to periodic acute stress that makes him hypervigilant, which increases cortisol levels. These stress patterns are carried over into adult life, which explains the correlation between ACE scores and many diseases in adulthood. For instance, high cortisol levels counteract insulin and bone formation and thus lead to diabetes and bone fractures. Low levels of cortisol are implicated in autoimmune disorders. The researchers noted that “high morning cortisol levels might be an adaptive response to the unpredictable, acute stressors experienced within emotionally maltreating environments. However, it is likely that this initially adaptive pattern of cortisol production would be less adaptive in new environments and would be detrimental to the children over time.”

19 Self-Hatred

At least six categories of the ACE Study cause the child to think she is worthless and unlovable. For instance, repeated humiliation produces “unbearable feelings of loneliness, despair, and inevitable rage of helplessness. Rage that has nowhere to go is redirected against the self, in the form of depression, self-hatred, and self-destructive actions.”[5]

Consider Pam, seven years old, an only child, living with both working parents who recently bought a “nice” house in the suburbs. Every Saturday morning is devoted to a family activity, cleaning the house. Invariably, her father, in a lousy mood, lines Pam up against a wall and shouts at her, “You are the stupidest kid in the world. Why can’t you ever do anything right?”

Pam experiences almost unbearable emotional pain; her father belittled her and reduced her to worthlessness. She has only two explanations; either her father is a bad person or she is. Pam knows that alone she is helpless and needs her father for survival, for food, shelter, and clothing, but above all else, she wants her father’s unconditional love, so her father cannot be a bad person. Without her father, she is lost, and she concludes that she is the bad person and not worthy of love. Pam suppresses her anger toward her father for his unjust treatment of her and, instead, directs her rage against herself.

Two paths are open to Pam. One: She is so unlovable that self-hatred controls her life. As a teenager and later as a young adult, she engages in self-destructive behavior — alcohol, street drugs, promiscuous sex, anything that will slowly kill her, a wretched being, anything that confirms her worthless.

Two: She will show her father and the world that she is worthy of love. Pam may decide to demonstrate that she is lovable by becoming physically attractive, a charming woman no one dislikes; everyone admires her beauty and grace. Or she may earn a Ph. D. in mathematics to prove that she was always the smartest kid on the block. Or she may go to graduate school at Stanford and then join the leadership team of one of the biggest firms in Silicon Valley. In our gender-fluid society, she may be the only source of income for her family; her spouse quits his job and becomes a stay-at-home dad.

But not one of these futures is satisfying. Underneath the success is the nagging fear that she is not loved for who she is. No one wants to be loved only for economic success, intellectual achievement, or physical beauty. Earned love always leaves the lingering doubt that one is not loved for oneself but for the status and pleasure that accrues to others. Earned love cannot be a substitute for unconditional love.

Despite the dissatisfaction, Pam is now addicted to the course of action she chose to earn love from others; being attractive, smart, or successful almost works; maybe the next time it will; so, Pam does Botox, writes another mathematics paper, or moves up to a better job — and on and on it goes, in an impossible, tragic quest for love. Her survival strategy as a child — I am unworthy of love — kept her connected to her father but was disastrous for her when carried over into adult life.

Attachment to Suffering

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh observed that “people have a hard time letting go of their suffering. Out of a fear of the unknown, they prefer suffering that is familiar.”[6]

Consider Katie, a patient of Alex Howard, the Founder of The Optimum Health Clinic and Conscious Life. Katie complained of depression, lack of motivation, and loneliness. She said, “I’ve been craving all my life to be loved and nurtured and cherished. I don’t know what it feels like to be unconditionally loved and to be the most important thing in somebody else’s eyes. I always felt unlovable.”[7]

Alex told Katie, “I think part of the reason why that’s so painful is because of the emotional neglect that you experienced as a child.”

A local firm sought Katie for a new job. She was shortlisted, interviewed, and offered the job. The same day she accepted the position, one of the campaigns she ran the previous year was nominated for an award. Instead of being elated over her new job and the nomination, her response to the good news was “Why am I doing this? You know, it’s all about seeking validation to prove to the world that I’m good enough, but it’s a big, big, big load of shit; I’m really none of those things. I want to just be me, but like I said, at the beginning, I don’t even know who Me is.”

Katie is caught in a double bind. From her adverse childhood experience, she concluded she was unlovable, which may have served her well as a child but not as an adult. Her success in the workplace earned her praise and commendations, not the unconditional love Katie yearned for. But to give up her identity as an unlovable wretch would require her to enter the scary domain of not knowing who she is. As much as Katie hates her life, it is not as painful as having no identity, free-floating in a void.

20 Memory Erasure

For over sixty years, psychologists and neuroscientists believed that the consolidation of a traumatic, emotional experience into long-term memory was a one-time irreversible process and that no procedure existed for erasing what had been solidified in the brain. Beginning in 1997, researchers discovered that long-term memories are not fixed forever; indeed, traumatic memories can be revised and even erased, in the sense that an acquired behavioral, emotional, or physiological response to a previous trigger is eliminated.[8]

Psychologists Bruce Ecker and Sara Bridges give the case history of Tina as an example of how memories of adverse childhood experiences can be erased.[9] Tina, 33, began her first session with a new therapist by confessing, “I’ve been feeling depressed and lousy for years. I have a black cloud around me all the time.” The absence of motivation, low energy, and social isolation caused her to lament, “I’m a vegetable. I’m a worthless nothing that nobody could possibly find interesting.” Past therapy, self-help groups, and a regime of Prozac had not tempered her depression or lifted the black cloud that enveloped her.

Under her new therapist’s persistent questioning about her early family life, Tina described painful memories of when she expressed her feelings, her mother and other family members verbally assaulted her, then, in conclusion, said lifelessly, “Saying what I’m really feeling or caring about gets me mowed down — so I don’t go there.”

The therapist asked, “And how do you keep yourself from ‘going there’?”

She answered with unexpected animation, “By being dead, apathetic, and telling myself I have nothing interesting to say!”

For the first time, she recognized that for self-protection, she had resorted to eliminating her own self-expression by deadening herself. Ecker and Bridges note that “her state of depression, lack of motivation and futility suddenly made deep sense to her in an entirely new way. Instead of viewing those symptoms as mystifying, out-of-control personal defects and pathology, she now recognized that they were . . . purposeful and effective tactics for keeping to a minimum the suffering that her family members were always ready to inflict” on her when she expressed her feelings.

Tina suddenly experienced two contradictory understandings of her plight: 1) The hopelessness, fear, despair, and aloneness she knew were her fault, and 2) The exhilaration that accompanied her discovery of the obvious truth that her childhood understanding of herself as a person of no interest to anyone was protection from her family. Blaming herself for her depression was disconfirmed by the truth and erased.

During the sixth and final therapy session, Tina blurted out her core understanding of her relationship with her mother: “Mom sees and knows everything I ever care about or do, and then takes over and takes away everything I ever care about or do, which feels devastating for me, and my only way to be safe from her pillaging is for me to care about nothing and do nothing.” As a child, Tina believed her mother was all-seeing, and she protected herself by zeroing herself out, so her narcissistic mother could no longer take credit for what she did.

To prompt Tina to find the needed truth to counter her all-seeing mother, the therapist said, “You feel just as vulnerable as ever to your mother taking things away. So, tell me: In what ways do people keep other people from just reaching in and taking away things?”

After a moment of reflection, Tina answered, “It’s as if there has been a ‘no walls’ rule all along. I think I’ve been obeying a ‘no walls’ rule.” She then expressed amazement at the possibility of “having walls” and keeping her personal affairs “behind walls” and totally unknown to her mother or others. That “behind walls’ existed and was available to her was a contradictory truth in opposition to her mental model of her mother as all-seeing.

She felt jubilant; the false understanding of her mother was erased. No further sessions were scheduled. Two years later, in a follow-up telephone conversation, Tina reported her life had been transformed by the therapy that erased her faulty picture of herself. She was nine months into a new career in computer programming and spoke about her future with enthusiasm. She said she was completely free of the black cloud and antidepressants and added, “Things are very good.” Clearly, the erasure of a memory can be life-altering.

Ecker and Bridges state that memory erasure has occurred in various systems of therapy, one of which is Tapping.

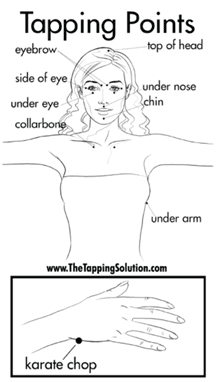

The tapping points are shown in the illustration. That tapping on a few acupressure points can relieve anxiety or chronic pain seems weird, if not downright New Age woo-woo, especially when its validity is given in terms of ch’i, the vital energy that animates any living entity, according to ancient Chinese medicine. When the flow of ch’i is impeded, sickness results; tapping on certain acupressure points releases ch’i and restores the body to health.

That tapping on a few acupressure points can relieve anxiety or chronic pain seems weird, if not downright New Age woo-woo, especially when its validity is given in terms of ch’i, the vital energy that animates any living entity, according to ancient Chinese medicine. When the flow of ch’i is impeded, sickness results; tapping on certain acupressure points releases ch’i and restores the body to health.

Today, how Tapping works is told in terms of a scientific story that begins with the amygdala, the threat detection part of the brain. While tapping on the karate chop point, a person mentally recalls the traumatic memory that puts the amygdala into the threat response mode. This setup instantly approximates the brain state the person was in during the traumatic event, if only to a slight degree. When the threat response has gone up, then the person sends a different signal by tapping on the other acupuncture points that decrease the threat response, so now the brain is getting two opposed signals: 1) The memory is increasing the amygdala threat response, and 2) The tapping is decreasing the threat response. With the amygdala receiving these two opposed signals, the signal that decreases arousal begins to predominate. The result is that the person still has the memory, but the associated threat response does not reoccur. The emotional component of the memory is significantly weakened and ideally eliminated altogether. In this way, a person is no longer controlled by a traumatic memory.[10]

In the accompanying video, Robert Smith, the founder of Faster EFT, discovered memory erasure by carefully examining his traumatic childhood memories. His mother ran away from her Oklahoma home to Texas when she was fourteen and went back home to give birth at fifteen to Robert. Smith never knew his biological father, and his mother may not of either.[11] His stepfather was the oldest of nine children, an alcoholic, and at one point in his life, all his brothers and sisters were in foster homes. His stepbrother, Steve, had been in prison two times, the next time for life. The stepfather came into Robert’s life when he was six months old. By the time his mother was nineteen, she had four children.

The stepfather lacked a high-school education, worked hard, lost jobs, and moved his family from home to home. Smith recalled that “my dad had a rough life. He would beat you at the drop of a hat. When he came home, we didn’t greet him at the door because it wasn’t safe.” Everyone on his father’s side of the family was an alcoholic. Smith remembers that the first time he got drunk, he was thirteen, and “It was one of the best things I ever had at the time.”

Smith went to college but could not pass English II; he tried three times and quit. He understood why he flunked English II: “I was not dumb. I had moved from school to school to school and had learning difficulties. I rode the small bus to school. You know what that means. That was the special school bus. The reason I had problems with English is that my English teachers didn’t understand where I was coming from. In this way, I discovered that most of our problems come from our past.”

The defining event in Smith’s difficult life happened when he was eleven. His stepfather had moved his family to a new house; Smith had moved to the third school in a year. Once again, in a new neighborhood, he was bullied. One day to avoid getting beaten up, he climbed a tree, boarding on the driveway of his new house. The bullies were throwing rocks at him when his stepfather pulled into the driveway.

The bullies backed off, and Robert climbed down from the tree and went to his stepfather for protection. The stepfather got out of the car, and he had a hammer in his hand. “He beat the crap out of me with his hammer, right in front of those bullies,” Smith later said, and added, “If I went to this memory at twenty-two, I would still feel intense emotional pain.”

Smith’s adverse childhood experiences placed him at high risk for suicide and a shortened life expectancy of twenty years or more. Instead, one day, he seized control of his life. He quit fleeing from the memory of his stepfather beating him with a hammer and observed that his memory was a series of images. “When I remembered the memory, I’m watching my father beat me with a hammer. It’s like I’m a fly on the wall. And I’m watching him do this. It’s impossible. It never really happened that way.” Smith discovered that the recall of a memory alters it. In Smith’s case, his defining traumatic childhood memory became part of his personal narrative, and thus, his memory was altered to accord with the viewpoint of the storyteller.

What happened next was startling. Smith explored this memory further: “I started looking at my father’s face and how he was looking, and I noticed that my father was angry, and I would tap. I kept tapping, and all of a sudden, my father’s face changed. Then I started looking at my face. I felt abused. I felt rejected. I kept tapping until that little boy inside me was smiling.

“I, then, focused on my father again. He had a hammer in his hand; he was beating me. I looked at the memory and tapped. I just tapped on it over and over again. Suddenly, my mind gave me something better. It put a fishing pole in my dad’s hand. And in my mind, I feel like my father said, would you like to go fishing? I said, sure, dad, and you know what? We went fishing. And the amazing thing about this is I happened to catch the biggest fish. I mean, it’s gigantic. And I could still see the look in my father’s eyes. He was envious of this great big fish.”

Smith acknowledges that he did not erase the actual event of his stepfather beating him with a hammer when he was eleven years old. What he did change were the emotions associated with the memory. The emotions power our memories; without an emotion, a memory has no power over us, as Smith realized through tapping. Today, he says, “I can tell this story, and it’s not my story.” I suspect that many, if not most of us, think that Smith replacing a real memory with a fake memory is a profound betrayal of who he is.

Endnotes

[1] Robert Anda, quoted by Jane Ellen Stevens, The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study — the largest, most important public health study you never heard of — began in an obesity clinic, October 3, 2012. Available https://acestoohigh.com/2012/10/03/the-adverse-childhood-experiences-study-the-largest-most-important-public-health-study-you-never-heard-of-began-in-an-obesity-clinic/.

[2] See Vincent J. Felitti et al., Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults, 1998 (Available https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(98)00017-8/fulltext.); Vincent J. Felitti, The Relation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead, Winter, 2002 (Available https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6220625/); and Vincent Felitti: Reflections on the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, June 21, 2016 (Available https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ns8ko9-ljU).

[3] Since the original ACE Study was published, thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia have collected ACE data. The data shows that between 55 and 62 percent of their populations had experienced at least one ACE category, and between 13 and 17 percent of their populations had an ACE score of four or more. See K. Gilbert et al., “Childhood Adversity and Adult Chronic Disease: An Update from Ten States and the District of Columbia, 2010. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 48, no. 3 2015): 345-49.

[4] Jacqueline Bruce et al., “Morning Cortisol Levels in Preschool–Aged Foster Children: Differential Effects of Maltreatment Type,” Developmental Psychobiology 51, no. 1 (2009): 14-23.

[5] Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (New York: Penguin, 2015), p. 136.

[6] Thich Nhat Hanh, Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life (New York: Bantam Books, 1991).

[7] Rediscover who you are | Katie #2 | In Therapy with Alex Howard (Available https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHTdI5Duq_s) and How to shift a NEGATIVE STATE | In Therapy with Alex Howard (Available https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fM-V4M1LjA4).

[8] Bruce Ecker and Sara K. Bridges, “How the Science of Memory Reconsolidation Advances the Effectiveness and Unification of Psychotherapy,” Clinical Social Work Journal (2020) 48:287–300, published online: 22 April 2020.

[9] Ibid.

[10] In the text, the term “traumatic memory” is used in common speech, not in the technical manner employed by psychiatrists such as Bessel van der Kolk: “Traumatic memories are fundamentally different from the stories we tell about the past. They are dissociated: The different sensations that entered the brain at the time of the trauma are not properly assembled into a story, a piece of autobiography.” (Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score, p. 136.)

[11] Ibid.