|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

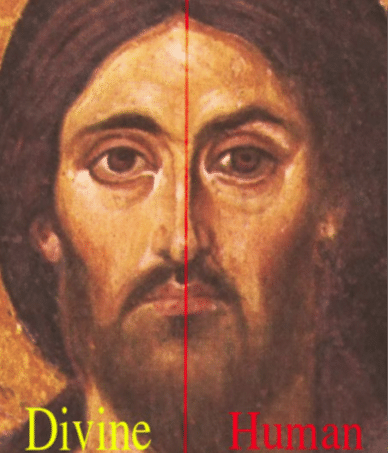

In 1500, Albrecht Dűrer painted a shockingly original self-portrait that anticipated the era of Modernity that followed. (See Figure 1.) Dűrer paints himself as a unique individual, as the one subject that fascinated him beyond all else. In the self-portrait, he is perfect, his skin bright and unblemished, his beautiful hair with strands that weave in and out, his fur-lined coat suitable for a nobleman.[1] That Dűrer fashioned himself after the holy icons of Christ is readily seen in his asymmetric eyes. (See Figure 2.)

The penetrating, divine eye of Christ sees everything inside the worshipper, while the human eye looks past him. In Christ-the-Pantocrator icons, the right hand of the Lord of the universe, the forefinger and middle finger slightly apart, blesses Creation. In the self-portrait, Dűrer, hand on heart, blesses himself as the center of Creation.

With supreme arrogance, Dűrer left behind the tradition that a painter never signed his work or painted a self-portrait. The unique, mysterious individual that Dűrer first painted will become an endless topic of study for painters, photographers, writers, and philosophers.

Perspective Painting

Dűrer was a brilliant innovator in the new art of perspective painting that developed in the Renaissance as a result of emerging individualism. Architect-historian F. G. Winter explains: “Perspective can be described as the most striking symptom of the new cosmic spirit which during the Early Renaissance brought about a basic transformation of mankind. In the non-perspective era of antiquity and the Middle Ages man felt himself to be part of the world; in the era of perspective he confronts it as an independent individual.”[2]

A system of linear perspective was first described in 1436 by Leon Battista Alberti in Della Pittura. Alberti likens the picture surface to “an open window through which I see what I want to paint.”[3] St. Jerome in His Study by Antonello da Messina is a perfect illustration of the Early Renaissance idea of a painting as a view through a window. The arched stone surround rests on a “window ledge.” (See Figure 3.)

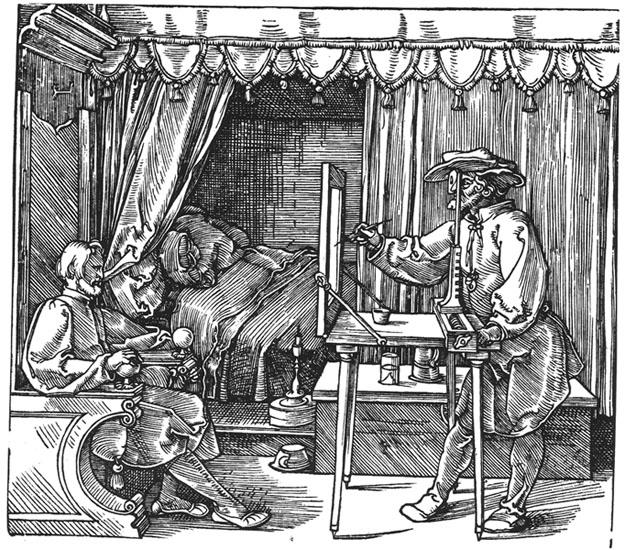

The perspective painter occupies a position outside of the world and paints the scene seen from a distance. In Figure 4, Dűrer illustrates how an artist renders a portrait in perspective with the aid of an eyepiece and a glass panel. The eyepiece fixes the artist’s eye as he copies the outlines of what he sees on the glass. In perspective art, the world is seen through a peephole.

Figure 4. Dürer’s device for rendering a portrait in perspective, 1525.

Art critic Robert Hughes explains that perspective is “an ideal view, imagined as being seen by a one-eyed, motionless person who is clearly detached from what he sees. It makes a god of the spectator, who becomes the person on whom the whole world converges, the Unmoved Onlooker.”[4]

Perspectivism Destroys the Whole

We are so accustomed to the frozen instant in time and space in Western painting that we believe it accurately represents how we see; however, perspective painting is a highly artificial abridgment of natural vision. Unlike the painter in Figure 4, our heads are not rigidly fixed, nor is the mobility of our eyes severely limited. When we look at something of any magnitude, our eyes and heads are in constant motion, and our peripheral vision tells us that we are surrounded by the world and not outside it.

Chinese landscape painting corresponds more closely to how we experience space and time in everyday life than the artifice of perspective painting. Chinese painters employ what art historian George Rowley calls a moving focus. By this device, a viewer “might travel through miles of landscape, might scale the mountain peaks or descend into the depths of the valleys, might follow streams to their course or move with the waterfall in its plunge.”[5] The lack of perspective places the viewer inside the landscape, rather than occupying a single viewpoint outside the painting. When present, the human element is always small and well-integrated into the cosmology of the picture.[6] (See Figure 5.)

Furthermore, Chinese paintings are not framed and thus convey unlimited space; for example, no heavy black border surrounds Traveling Through Gates and Passes.

Renaissance painters restrict space “to a single vista as though seen through an open door;” Chinese painters suggest “the unlimited space of nature as though they had stepped through that open door and had known the sudden breath-taking experience of space extending in every direction and infinitely into the sky.”[7]

Keri Burnor, an art student, describes her first visit to the Oriental collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts: “Books and reproductions cannot do justice to the beauty of Chinese painting. I could actually feel myself walking amongst the birds and walking along the paths in the paintings. The paintings seemed to come to life! I could see the trees blowing in the wind; I could almost hear the river rushing by. I walked through many scenes, saw temples in villages, and roamed through mountains until a bamboo branch finally slapped me in the face!”[8]

Art historian Gyorgy Kepes explains how Western pre-Renaissance painters strove to represent a connectedness in meaning: “Early medieval painters often repeated the main figure many times in the same picture. Their purpose was to represent all possible relationships that affected him, and they recognized this could be done only by a simultaneous description of various actions.”[9] (See Figure 6.)

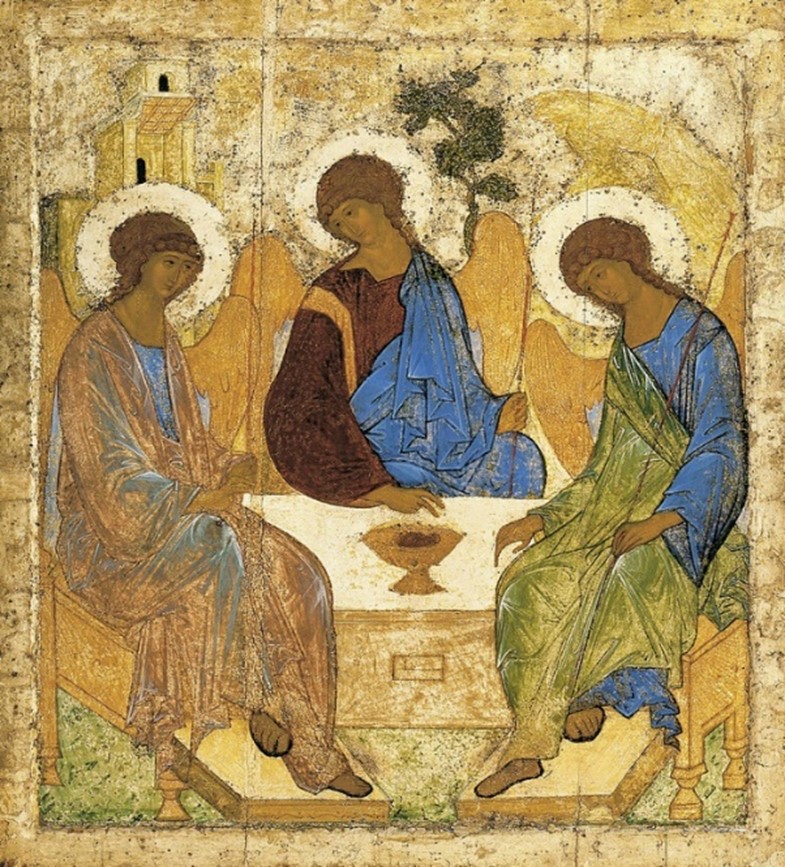

Many icons are written in inverse perspective, where the vanishing points are in front of the painting, so the farther an object is from the viewer, the larger it appears. The icon The Trinity, also called The Hospitality of Abraham, by Andrei Rublev, invites the viewer to join in a union with the Holy Trinity to complete the circle of angles. The figures are arranged so that the lines of their bodies form a full circle. In motionless contemplation, each angel gazes into eternity.

The Fixed Point of View

When Greek tragedy was rediscovered during the Renaissance, the first performances were in theaters that copied the Greek amphitheater’s circular layout. But the theater-in-the-round later gave way to the proscenium-arch stage that places the action inside a picture frame. The modern stage provides only one point of view, and consequently, each member of the audience is a detached spectator, instead of a participant, as in ancient Greek theater.

From the Greek chorus to Gregorian chant, singing was also communal; but during the Renaissance, and for the first time in Western music, an individual singer is separated from the chorus, and a new form of music, opera, featured the solo voice. The first opera, Dafne, by the Roman-born composer Jacopo Peri and Florentine poet Ottavio Rinuccini, was performed in 1597. In the modern concert hall, the audience sits passively in neat rows in front of the musicians. The listeners have learned to suppress the natural impulse to sing along, clap out the rhythm, and participate in the musical performance.

The reader of a book is not unlike the detached spectator in the modern theater. Prior to the invention of the modern narrative, no work of Western literature was told in a consistent voice from a single point of view. Such universal stories as myths, Aesop fables, and folk tales that begin “Once upon a time . . .” do not have a narrator. Medieval literature usually employed multiple narrators. For instance, in Boccaccio’s Decameron, ten narrators tell a tale a day for ten days. Even such an early modern work as Don Quixote has two principal voices, that of Cid Hamete Benengeli and that of the editor who found the Arab historian’s manuscript. Media theorist Marshall McLuhan observes that the discovery of “equitone prose” preceded the invention of the novel: “Addison and Steele, as much as anybody else, had devised this novelty of maintaining a single consistent tone to the reader. It was the auditory equivalent of the mechanically fixed view in vision.”[10]

Literature

Individualism begins to shape the literary arts in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Critic Ian Watt explains what was new about the novel, a genre invented during this time: “Descartes did much to bring about the modern assumption whereby the pursuit of truth is conceived of as a wholly individual matter, logically independent of the tradition of past thought, and indeed as more likely to be arrived at by a departure from it. The novel is the form of literature which most fully reflects this individualist and innovating reorientation.”[11] Previous literary forms, such as Classical poetry and the Renaissance epic, took their plots from past histories or fables and sought to embody what is universally human. New works were judged largely according to how well they conformed to traditional practice. “This literary traditionalism was first and most fully challenged by the novel, whose primary criterion was truth to individual experience — individual experience which is always unique and therefore new.”[12]

Unlike their immediate predecessors — Spenser, Shakespeare, and Milton — the first novelists did not take their plots from mythology, legend, history, or ancient literature, nor did they seek to present universal truths about human nature. “Defoe initiated an important new tendency in fiction: his total subordination of the plot to the pattern of autobiographical memoir is as defiant an assertion of the primacy of individual experience in the novel as Descartes’ cogito ergo sum was in philosophy.”[13]

In the seventeenth century, first-person novels quickly became popular, as did epistolary novels that reveal intimate, secret details about fictional characters through their letters to each other. At this same time, keeping diaries came into vogue. The diary is the most radically personal form of literature: written by one person about one person’s thoughts, actions, and feelings and intended for an audience of one. Samuel Pepys kept a diary for nine years. Writing in code to guarantee his privacy, he logged one and a quarter million words about the most trivial events in his private life.

Writing by oneself, about oneself, for oneself gives rise to another genre, the autobiography, in which the author glories in his ineffable uniqueness, warts and all. Rousseau in his Confessions informs the reader that “I am made unlike anyone I have ever met; I will even venture to say that I am like no one in the whole world. I may be no better, but at least I am different. Whether Nature did well or ill in breaking the mold in which she formed me is a question that can only be resolved after reading my book.”[14]

Alexis de Tocqueville predicted, “Among a democratic people poetry will not feed on legends or on traditions and memories of old days. The poet will not try to people the universe again with supernatural beings in whom neither his readers nor he himself any longer believes, nor will he coldly personify virtues and vices better seen in the natural state.”[15] Literary critic Harold Bloom’s observation about the history of poetry in the English language confirms Tocqueville’s prediction: “Before Wordsworth, poetry had a subject. After Wordsworth, its prevalent subject was the poet’s own subjectivity.”[16]

Religion

Martin Luther, in 1517, affixed to the church door in Wittenberg his Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, later known as the Ninety-Five Theses that initiated the Reformation. Three principles defined the Protestant Reformation: The Bible as the sole authority, justification by faith alone, and the priesthood of all believers. All three served to substitute the individual for the community. Instead of submitting to the Church’s explanations of the Bible, the Protestant turned to private interpretation. Instead of relying on the spiritual direction of priests and the prayers of Church members, each Protestant struggled alone for his or her salvation, not through any form of intercession but by individual effort and personal faith in Christ the Savior. All believers were equally thought to be priests. “For whoever comes out of the water of baptism can boast that he is already a consecrated priest, bishop, and pope,” Martin Luther taught.[17] In effect, each Protestant became his or her own church.

“The quintessentially modern idea of the individual — and of one’s personal responsibility before one’s self and God rather than before any institution, whether church or state — was as unthinkable before Luther as is color in a world of black and white,” writes Eric Metaxas in his biography of Luther.[18]

The Reformation launched individualism and thereby destroyed medieval communal life. Protestantism replaced the community by the individual; the new man of God was to achieve “salvation through unassisted faith and unmediated personal effort.”[19]

In the New World, the Puritans put an indelible stamp of individualism upon America. After a livelong study of Puritanism, historian Perry Miller writes, “The Protestant sense of the individual, of the single entity which is one entire person, who must do everything of himself, who is not to be cosseted or carried through life, who in the final analysis has no other responsibility but his own welfare, this ruthless individualism was indelibly stamped upon the tradition of New England . . . . Both in economics and in salvation, the individual had to do everything of himself.”[20]

Philosophy

Shortly after Martin Luther’s death in 1546, the primacy of the individual begins to dominate philosophy. Essayist Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533-1592) not only takes the self as the source of all knowledge, but he makes it the central object of philosophic contemplation: “I study myself more than any other subject. That is my metaphysics, that is my physics.”[21] He describes his essays as “my fancies by which I try to give knowledge not of things but of myself.”[22] In his view, philosophy is not wisdom at the service of the community but an introspective and autobiographical enterprise. Montaigne describes his work in these words, “This book was written in good faith, reader. It warns you from the outset that in it I have set myself no goal but a domestic and private one. I have had no thought of serving either you or my own glory.”[23]

René Descartes, the father of modern philosophy, emulates Montaigne in attempting to derive all truth from the self. In his Discourse on Method (1637), Descartes gives a brief intellectual autobiography. He attended the most celebrated schools in Europe, receiving an excellent classical education; yet, the more he studied, the more he discovered his ignorance and that of his professors. After earning the baccalaureate and licentiate degrees in law, he left the university to study the “great book of the world.”[24] However, he found as much diversity in the customs of humanity as he had earlier seen in the opinions of the philosophers. Consequently, Descartes resolved to make himself an object of study: “This succeeded much better, it appeared to me, than if I had never departed either from my country or my books.”[25]

The Thirty Years War and the harsh winter of 1619 forced Descartes to take up temporary quarters in Germany. “I remained the whole day shut up alone in a stove-heated room, where I had complete leisure to occupy myself with my own thoughts.”[26] Descartes meditated upon the disunity and uncertainty of the knowledge of his day. He marveled at mathematics and wondered why the certainty and evidence of its arguments had not been used as the foundation for all knowledge. Unlike philosophers, mathematicians possessed genuine knowledge, for the demonstrations of geometry were so evident and clear that no one disputed them. Then, in a blinding flash, Descartes conceived of a method to put all knowledge on a footing as secure as that of mathematics. He explained that the essence of his new method is to commence “with objects that were the most simple and easy to understand, in order to rise little by little, or by degrees, to a knowledge of the most complex.”[27] Now known as Cartesian reductionism, Descartes’ method has two steps: First thoroughly understand the simplest parts, and then construct the whole as a sum of the parts. Descartes believed the reason mathematicians give such certain demonstrations is that they follow the Cartesian two-step procedure.

Descartes was the first person to enunciate the defining principle of Modernity: Every whole — a political community, a horse, or a carbon atom — is a sum of its isolated parts. Tocqueville was the first person to use the word “individualism” and reports “that word ‘individualism,’ which we coined for our own requirements, was unknown to our ancestors, for the good reason that in their days every individual necessarily belonged to a group and no one could regard himself as an isolated unit.”[28] The overarching principle of Modernity is that things exist in isolation as separate entities. The Latin word “indīviduum,” the root of the English word “individual,” means an indivisible whole existing as a separate entity.

I Think; Therefore, I Am

Descartes also describes in the Discourse on Method how he conducted a philosophic experiment to find the most simple and easy to understand principle that would provide the unshakable foundation philosophy and science. To determine if he could know anything with certitude, he rejected as false anything he had the least occasion to doubt. Since the senses sometimes deceive, he supposed that nothing is as the senses report. Furthermore, since he had made mistakes in reasoning, he rejected as false all the arguments that he had previously taken for demonstrations. But he soon observed that for a person to doubt that he or she is doubting is a manifest logical contradiction: “I noticed that whilst I thus wished to think all things false, it was absolutely essential that the ‘I’ who thought this should be something, and remarking that this truth ‘I think, therefore I am’ was so certain and so assured that the most extravagant suppositions brought forward by the skeptics were incapable of shaking it, I came to the conclusion that I could receive it without scruple as the first principle of the Philosophy for which I was seeking.”[29]

In this way, Descartes claimed to have found the keystone of philosophy by considering himself as an isolated individual, separate from the Western tradition, separate from his experience of the “great book of the world,” and separate from nature. Modern philosophy, therefore, began with the isolated, autonomous individual and the demand that personal experience as a trustworthy path to knowledge be replaced by logical demonstration.

We Are All Cartesians Now

Tocqueville toured America for eighteen months, beginning in May 1831, and noted, “Less attention, I suppose, is paid to philosophy in the United States than in any other country in the civilized world.”[30] Even today, many, if not most Americans, find philosophy a bore and totally irrelevant to their lives. Yet, Tocqueville observed that “of all countries in the world, America is the one in which the precepts of Descartes are least studied and best followed.”[31] What a paradox!

“Americans have needed no books to teach them [Descartes’] philosophic method, having found it in themselves.”[32] Social equality produces a disposition not to trust the authority of any person, and hence, “there is a general distaste for accepting any man’s word as proof of anything.”[33] As a result, “in most mental operations each American relies on individual effort and judgment.”[34] Just like Descartes, Americans employ the philosophical method “to seek by themselves and in themselves for the only reason for things.”[35]

Before Descartes, no philosopher considered himself as an individual unit separate from community and tradition. In Medieval Europe, an “aristocracy link[ed] everybody, from the peasant to the king, in one long chain;”[36] for modern democracy to emerge, those links had to be broken. We moderns cannot base our beliefs on tradition, custom, or class. Our constant reference point is ourselves. As a result, we form the habit of always thinking of ourselves in isolation from other persons, and this habit carries over when we think about things. In this way, we acquire a culturally-given habit of thinking: To understand something, isolate it, so it exists apart from all relations.[37]

One conclusion Tocqueville drew from his study of American life is that the Cartesian method is “not just French, but democratic; and that explains its easy admission throughout Europe.”[38]

We Are on the Wrong Side of History

In Old Europe, like in every premodern culture, the group was considered prior to the individual in origin and authority. Jacob Burckhardt, the great scholar of the Italian Renaissance, explains that in Medieval Europe, a “man was conscious of himself only as a member of a race, people, party, family, or corporation.”[39] When asked “Who are you?”, a person may have replied, “A Vignola from Padua, a stone carver, and a good Christian.” Sociologist Robert Nisbet agrees that in Medieval Europe, “the group was primary; it was the irreducible unit of the social system at large.”[40] Since the whole is seen as prior to and greater than any of its parts, the overarching principle in Medieval Europe, as well as in all premodern cultures, is things exist only in relationship.

Unfortunately, we moderns are on the wrong side of history, for the cultural principle things exist in isolation is false — no indivisible part exists as a separate entity. If we were reared from infancy as isolated individuals, as separate entities, we literally could not understand what we see. For human vision to be meaningful, a person must be a participant in the world. This surprising property of vision was demonstrated in a series of classic experiments by Theodor Erismann.[41] He fitted persons with vision-distorting goggles that made straight lines appear curved, right angles seem acute or obtuse, and distances seem expanded or shortened. Amazingly, after a few days, a subject’s vision was no longer distorted; he saw normally and functioned normally, even skiing and riding a motorcycle!

The key to vision returning to normal was that the subjects were allowed to move about and act freely, enabling the strange new visual data to be integrated with the subject’s experience of self-movement and self-sensation through touch. Subjects not allowed to move on their own, though they were pushed on gondolas through the environment, never experienced normal vision while wearing the distorting goggles.[42] To see the world, we must be participants, not mere spectators.

The senses are meant to be engaged with the outside world, and the mind with something other than itself. In isolation, the senses and the mind create phantoms. Experiments on human subjects in isolation tanks demonstrated that extreme sensory deprivation induces psychic disorders, such as mental confusion, hallucinations, and panic.

A human being exists only in relationship. Perceiving, feeling, imagining, thinking, and willing are impossible in isolation. A person in isolation from a larger whole, say nature or community, is a meaningless abstraction, an idealization that can only occur in philosophy and political theory. When Descartes retired to his stove-heated room in “isolation,” he took with him language, past conversations, memories of the books he had read, and intellectual and emotional habits. In effect, he brought into the room all Western culture, even how it poses questions and the answers it accepts. The isolated, autonomous self is a cultural myth, whose realization would reduce a person to nothingness.

To conform our thinking to the way things are, we must replace the Cartesian mantra “begin with the smallest parts” with the new mantra “begin with the whole.”

You and I Are Cultural Constructs

Everyplace we turn to in modern life, whether taking a selfie, unknowingly imitating Dűrer, or turning to religion, philosophy, literature, or art, we meet ourselves — isolated, autonomous individuals. We result from the gradual decline of a group-centered culture and its replacement by the individual-centered culture in which we now live.[43] “The fundamental assumption of Modernity, the thread that has run through Western civilization since the sixteenth century, is that the social unit of society is not the group, the guild, the tribe, or the city, but the person,” sociologist Daniel Bell observed.[44] From their extensive study of how various cultures understand the self, social psychologists Hazel Rose Markus and Shinobu Kitayama concluded that in the modern West, the individual is viewed as an “independent, self-contained, autonomous entity.”[45] Anthropologist Clifford Geertz pointed out that such a conception of the self is unique in the world’s cultures.[46] In premodern Africa, for instance, a person regarded himself or herself “as a rather insignificant part of a much larger whole — the family and the clan — and not as an independent, self-reliant unit.”[47]

In my youth, I, a cultural construct, believed I was an island unto myself and that I had freely chosen my way of life with no regard to what others thought of my odd, eccentric behavior; I owned myself and my abilities; I owed nothing to any individual, except what I voluntarily incurred through social agreement or legal contract.

Then, I read Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America and discovered that the individualism of the New World inculcated Cartesian thinking in me; as a result, like a trained parrot, I vociferously and probably obnoxiously tried to convince my friends in philosophy and literature that they were fundamentally deluded, for the universe, including their misguided thinking, could be explained by brain physiology. Tocqueville, not my friends, persuaded me that I was an idiot, intellectually unaware of how modern culture shaped my interior life. Culture gives every person the tools for human living as well as a self. I had wholeheartedly believed the democratic myth that I was the King of the Castle, picking and choosing the fundamental aspects of how I lived, deciding what is true and false, what is morally good and bad, what is beautiful and ugly. Just like Descartes, I had the conviction that I exist could not be doubted, that I was the bedrock of all knowing, the center of existence.

Neither you nor I were born ready to engage the world. We had to learn a language, be given a social code, and acquire habits of thinking and feeling. If shortly after my birth in Pontiac, Michigan, I were adopted by a Lakota family in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, or a couple in Beijing, China, George Stanciu would not exist.

That different cultures produce different “I”s is apparent in the twenty-first century. In America, the “I” is quick to anger; in the Etku Eskimo community, the “I” seldom experiences anger. The American “I” wishes for others to fail and becomes envious when they succeed, while the Lakota “I” takes pleasure in others’ success. In America, the “I” is always lonely; in China, the “I” feels lonely only when separated from a lover or the family. To understand anything, the American “I” first looks to the smallest parts, while the Hopi “I” turns to the whole. The American “I” does not accept any man’s word as proof of anything, while the Japanese “I” seeks guidance from masters. The American “I” demands scientific demonstrations, whereas the Eastern Indian “I” wants a direct experience of the eternal.

Are You and I No More Than Social Constructs?

In the Western and Eastern wisdom traditions, the truest answer to “Who am I?” is arrived at by stripping away the accidents of birth and culture until the true self appears, timeless and in some mysterious way connected to all existence. For me, of course, this true self was a complete mystery, so after stumbling around for years exploring Hinduism and Buddhism, I turned to the deepest understanding of the human person that Christianity offers.

The Patristic Fathers embraced the theological insights of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopogite[48]: God is not any of the names used in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, not God of gods, Holy of holies, Cause of the ages, the still breeze, cloud, and rock.[49] God is not Mind, Greatness, Power, or Truth in any way we can understand, for He “cannot be understood, words cannot contain him, and no name can hold him. He is not one of the things that are, and he is no thing among things.”[50] God is the Unnamable.

Surprisingly, Thomas Aquinas, the most rational of theologians, also reached the conclusion that God is beyond our comprehension: “It is because human intelligence is not equal to the divine essence that this same divine essence surpasses our intelligence and is unknown to us: wherefore man reaches the highest point of his knowledge about God when he knows that he knows Him not, in as much as he knows that that which is God transcends whatsoever he conceives of Him.”[51]

According to St. Gregory Palamas, we know the energy of God, not His essence: “Not a single created being has or can have any communion with or proximity to the sublime nature [of God]. Thus, if anyone has drawn near to God he evidently approached Him by means of His energy.”[52] A person becomes close to God by participating in His energy, “by freely choosing to act well and to conduct [himself] with probity.”[53] Here, Gregory distinguishes between God’s essence, or substance (ousia), and His activity (energeia) in the world. The energy of God is experienced as Divine Light, such as the light of Mount Tabor or the light that blinded St. Paul on the Road to Damascus.

The Church Fathers, however, warned that for most devout Christians visions and heavenly voices do not come from God but from a fevered imagination and are distractions in the spiritual quest. Modern spiritual directors issue the same warning about imagined experiences. Thomas Merton, for example, told his novices that “since God cannot be seen or imagined, the visions of God we read of the saints having are not so much visions of Him as visions about Him; for to see any limited form is not to see Him.”[54]

Given this understanding of God, the image of God within us means that the essence of each one of us is unnamable and that we are known to others only through our activity in the world, that is, through a socially-constructed self. We are unknowable to ourselves, although through meditation, or what the Patristic Fathers called contemplation, we can witness our thoughts, memories, and storytelling, and thus know that as a matter of observable fact that we are separate from our thoughts and memories, that we are not what we witness. Through more advanced contemplation, we may experience Divine Light, the presence of God.

At the core of our being is the unnamable, the “empty mind” of Zen Buddhism, the “pure consciousness” of Hinduism, and the “spirit” of Christianity, although all words ultimately fail to capture our true self. We, the unenlightened, believe that the false self given to us by culture is permanent and fail to see that the false self is an illusion, with no more permanency than a smoke ring, destined to vanish with the death of the body.

Because we take our culturally-given self for our true self, we fail to experience who we truly are. Our true self is always present, completely perfected with no need for development from us; we must merely step aside. Every spiritual master calls for the death of the culturally-given self and a spiritual rebirth beyond egoistic desires, beyond religious practices, beyond any given culture, beyond the dictates of society, into the law of love, into compassion for every living being.

Like every person, I live in two worlds, the temporal and the eternal. I love the pungency of Stilton cheese, the softness of cashmere, the dance of cherry blossoms, and the smell of the ocean salt air, and wonder about the abundant beauty of Nature, where nothing is not beautiful, either to the eye or to the mind, and am enthralled by the poetry, drama, and music that touch the transcendent. Yet, this physical world, like “George Stanciu,” is transient and eventually vanishes without leaving a trace.

I live among the rich and the poor, the powerful and the weak, the ambitious and the lazy, the good and the bad, the loving and the hateful. Grappling with the death of my invented self taught me how to live in this world. I now see that every person I meet in ordinary, daily affairs — the mailman, the bank teller, the butcher at Whole Foods, the obnoxious teenager down the street with his blaring boom box — is part human and part divine, a storytelling self, often confused, dislikable, and in pain, but always transient, and a mysterious self, deathless, an image of God, worthy of unconditional love.

All images are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Endnotes

[1] For an excellent discussion of Dűrer’s Self-Portrait (1500), see Jason Farago, Seeing Our Own Reflection in the Birth of the Self-Portrait.

[2] F.G. Winter, “Postscript” to Willy A. Bärtschi, Linear Perspective: Its History, Directions for Construction, and Aspects in the Environment and in the Fine Arts, trans. Fred Bradley (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1981), p. 249.

[3] Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, trans. John R. Spencer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966 [1436]), p. 56.

[4] Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New (New York: Knopf, 1981), p. 17.

[5] George Rowley, Principles of Chinese Painting (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947), p. 62.

[6] See David Hinton, Awakened Cosmos: The Mind of Classical Chinese Poetry (Boulder, CO: Shambhala, 2019), p. xiv.

[7] Ibid., pp. 61-62.

[8] Keri Burnor, private communication.

[9] Gyorgy Kepes, Language of Vision (Chicago: Paul Theobald and Company, 1964), p. 96.

[10] Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Bible: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962), p. 273.

[11] Ian Watt, The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957), p. 13.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., p. 15.

[14] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Confessions, trans. J. M. Cohen (Middlesex: Penguin, 1954), p. 17.

[15] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Harper & Row, 1966 [1835,1840]), p. 487.

[16] Harold Bloom, The Best Poems of the English Language: From Chaucer Through Frost (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), p. 323.

[17] Martin Luther, “Open Letter to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation,” in Martin Luther, Three Treatises, trans. Charles M. Jacobs (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1960), p. 14.

[18] Eric Metaxas, Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World (New York: Viking, 2017), p. 1.

[19] Robert A. Nisbet, The Quest for Community (New York: Oxford University Press, 1953), p. 90.

[20] Perry Miller, “Individualism and the New England Tradition,” in The Responsibility of Mind in a Civilization of Machines: Essays by Perry Miller, ed. John Crowell and Stanford J. Searl, Jr. (Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1979.), p. 5, 6.

[21] Michel de Montaigne, “Of Experience,” in The Complete Essays of Montaigne, trans. Donald M. Frame (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1958), p. 821.

[22] Montaigne, “Of Books,” in Complete Essays, p. 296.

[23] Montaigne, “To the Reader,” in Complete Essays, p. 2.

[24] René Descartes, Discourse on Method in The Philosophical Works of Descartes, trans. Elizabeth S. Haldane and G.R.T. Ross (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), vol. I, p. 86.

[25] Ibid., p. 87.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid., p. 92.

[28] Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Régime and the French Revolution, trans. Stuart Gilbert (New York: Doubleday, 1955 [1856]), p. 96.

[29] Ibid., p. 101.

[30] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 429.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid., p. 430.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid., p. 429.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid., p. 508.

[37] For a more complete discussion of the modern habits of thinking, see George Stanciu, The Fetters of ‘Free Thought’.

[38] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 431.

[39] Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans. S. G. C. Middlemore (New York: Modern Library, 1954), p. 100.

[40] Robert A. Nisbet, The Quest for Community (New York: Oxford University Press, 1953), The Quest for Community, p. 81.

[41] See Ivo Kohler, The Formation and Transformation of the Perceptual World, trans. Harry Fiss (New York: International Universities Press, 1964).

[42] See Richard Held, “Plasticity in Sensory-Motor Systems,” Scientific American 213 (November 1965): 84-94.

[43] Most scientific cross-cultural studies contrast collectivist and individualist societies, which to my ear, indicates the prejudice that modern Westerners are superior to East Asians and Native Americans. Who wants to be collectivist, mindlessly following the dictates of the group? Wouldn’t you rather be an individualist, the Marlboro Man, subservient to no one? We adopt the neutral terminology, group-centered and individual-centered.

[44] Daniel Bell, The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 1976), p. 16.

[45] Hazel Rose Markus and Shinobu Kitayama, “Culture and Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation,” Psychological Review 98 (1991): 224.

[46] Clifford Geertz, “On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding,” American Scientist 63 (January-February 1975): p. 48.

[47] J. C. Carothers, “Culture, Psychiatry, and the Written Word,” Psychiatry 22 (Nov. 1959).

[48] Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite is the anonymous theologian of the late 5th to early 6th century whose works were erroneously ascribed to Dionysius the Areopagite, the Athenian convert of St. Paul mentioned in Acts 17:34.

[49] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Divine Names in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 596A.

[50] Ibid., 872A.

[51] Aquinas, Quaestiones Disputatae De Potentia Dei, trans. English Dominican Fathers (Westminster, MD: Newman Press, 1952, [1932]),Q. VII: Article V.

[52] Gregory Palamas, Topics of Natural and Theological Science and on the Moral and Ascetic Life: One Hundred and Fifty Texts in The Philokalia, Vol. IV, ed. and trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1984), p. 382.

[53] Ibid., p. 383.

[54] Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation (New York: New Directions, 1962), p. 132. Italics in original.