|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

On the final page of The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald captures the tragedy of America with the metaphor of the green light. Daisy always had “a green light that burn[ed] all night at the end of [her] dock,”[1] and Gatsby’s dream of possessing her had “seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it.”[2] Yet, the green light of his dream always receded, so Gatsby could never incarnate his romantic vision of his life with Daisy.

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning —— So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”[3]

In these last lines of The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald shifts from Gatsby to us, and implies that we Americans, with the settling of the New World and ever since, have been pursuing a green light that keeps receding from us. I wish to suggest that the green light for us flashes three different beams, prosperity, equality, and individualism.

Prosperity Equals Happiness

Alexis de Tocqueville contrasted how Europeans in the early nineteenth century imagined the New World to how Americans actually behaved: “Europeans think a lot about the wild, open spaces of America, but the Americans themselves hardly give them a thought. The wonders of inanimate nature leave them cold, and, one may almost say, they do not see the marvelous forests surrounding them until they begin to fall beneath the ax. What they see is something different. The American people see themselves marching through wildernesses, drying up marshes, diverting rivers, peopling the wilds, and subduing nature.”[4]

The first colonists of America were possessed by the dream of seizing the abundant riches of the New World and brushed aside the initial wonder momentarily evoked by pristine nature. Fitzgerald imagines what greeted the Dutch sailors’ eyes when they first saw the islands that were later to become New York City and the site of Gatsby’s mansion: “For a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”[5]

The history we learn in grade school is quite different. By the sixth grade, every schoolchild in America has learned that the Puritans fled to America to escape religious persecution in England and that they believed the prosperity they achieved in the New World was a sign of God’s blessing. What I did not learn in grade school was the degree to which the Puritans understood economic activity as part of God’s plan.

The Colony of Massachusetts Bay enjoyed ten years of unprecedented prosperity, when suddenly, in 1641, the Colony fell into an economic depression because the Long Parliament in England revived the Puritan cause at home. Immigration to the New World ceased, and without new buyers, without gold and silver from the Old World, the market for locally produced goods collapsed.

But God had pre-determined the prosperity of His People, so that the true church polity, the Congregational, would light the way for the rest of mankind. God, in His infinite Providence, contrived that the Catholics would continue to eat fish on Fridays, and He created the cod off the banks of Newfoundland and the depression of 1641, so the Puritans would engage in pious labor, rewarded with gold and silver from the errant Catholics.[6]

The notion of pious labor to fulfill God’s plan quickly disappeared in America. In the New World, a landed gentry, an established church, and a class based on birth did not exist. As a result, America “opened a thousand new roads to fortune and gave any obscure adventurer the chance of wealth and power.”[7] The equality of conditions in the New World drew immigrants intent upon acquiring material goods, and the emerging middle class sought physical comfort and an easier way of living. In present-day America, there is a widespread devotion to material possessions and physical comfort at the expense of intellectual and spiritual values, which is the common understanding of materialism. Virtually, no one in America escapes being a materialist.

From my personal observations, first-generation Americans embrace materialism more thoroughly than their immigrant parents. My sister, trying to correct my indifference to earning money, admonished me, “You have the education to live exceedingly well. That’s why our parents did what they could for you and me.” She, then, enumerated many of her possessions—a palatial home in Costa Mesa, California, three new cars, a boat docked at a slip in Newport Beach, and quarterly trips to Las Vegas, and cruises to Mexico and Hawaii—and said, “Our parents gave us the opportunity to have all this, to live the good life without killing ourselves, like they did.”

For many Americans, buying, owning, and consuming material goods are the essence of the good life. One of my sisters-in-law told me, “Our society is based on buying stuff.” Whenever she is having a bad day at her job, nothing makes her happier than to go out after work and shop for a new wardrobe. She, at that moment, feels like a new person, prettier and smarter. In this late stage of capitalism, products are therapy for the disenchanted soul; the right dress, haircut, or smartphone produces momentary personal happiness and enhanced self-esteem, filling a void in the soul.

My other sister-in-law sees the buying, owning, and consuming of material goods as a way to improve her social status. She scours Vanity Fair and Town and Country to learn what the beautiful people wear and believes in her fantasies that she will be one of them, if she acquires the right opinions, tastes, and labels. The marketers at Lacoste and Janzen, the first companies to put a logo on the outside of clothing, were geniuses.

In early America, before the Industrial Revolution, material desires were limited by nature and handicraft production. But two elements of capitalism—free markets and the division of labor—changed everything. Without the “great mass of inventions”[8] that continually flowed from science and technology, capitalism would have ground to a halt once markets were saturated by an abundance of goods. To continue to exist, the capitalist economy must continuously produce new consumer goods, not unlike a shark that must keep swimming or die. New inventions and technologies produce new goods and thus previously unknown desires, and in this way, we are all placed on the treadmill of desiring more and more, chasing the green light, prosperity equals happiness. If the iPhone (n) didn’t make you happy, no matter, the iPhone (n+1) will.

Two hundred years of capitalism in America created for the wealthy and the poor a superabundance of goods. The typical Walmart Supercenter carries 142,000 different items. A shopper at Kroger’s or Whole Foods can buy blueberries in December grown in Peru, fresh roses flown in from Columbia, and organic lamb imported from New Zealand.

Americans are incredibly wealthy by historical standards. Everyday, labor-saving machines such as clothes washers, electric ovens, and gas-fired furnaces are taken for granted. Most readers of this essay have access to precious medical advances, such as genetically-engineered pharmaceuticals, laparoscopic surgery, and magnetic imaging devices.

Laptops, flat-screen TVs, and smartphones are everywhere, in the ghetto as well as aboard yachts, which is not to deny the scandal that three million children in America live in abject poverty, the kind found in Bangladesh, one of the poorest countries in the world[9] or to discount the marked increase in midlife mortality of white, non-Hispanic Americans, the result of “deaths of despair” caused by drug addiction, alcoholism, and suicide in a declining middle class.[10]

Yet, the happiness supposedly brought about by prosperity alludes us. In America, from 1940–1995, as income increased, people reported a decrease in happiness, according to the Statistical Abstract of the United States.[11] Psychologist Daniel Kahneman and economist Angus Deaton analyzed the responses of more than 450,000 United States residents surveyed in 2008 and 2009 about their emotional well-being. Kahneman and Deaton focused on an “individual’s everyday experience—the frequency and intensity of experiences of joy, stress, sadness, anger, and affection that make one’s life pleasant or unpleasant.” They sought an answer to the question, “Does money buy happiness?” Not surprisingly, “low income exacerbates the emotional pain associated with such misfortunes as divorce, ill health, and being alone.” Unexpectedly, Kahneman and Deaton discovered that emotional well-being does not increase significantly beyond an annual household income of $75,000. “More money does not necessarily buy more happiness.”[12]

While advanced medical technology is making substantial progress in treating the physical diseases of Western civilization—cancer, atherosclerosis, and diabetes—the diseases of the interior life are taking over—alcohol and drug abuse, sex addiction, binge eating, and depression. From interviews with 39,000 persons, the authors of a paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association concluded that in the industrialized world, the rates of severe, often incapacitating depression have increased in each succeeding generation since 1915.[13] A 2011 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that between 1988 and 2008, the rate of antidepressant use by all ages in the United States increased by nearly 400 percent; 11 percent of Americans aged 12 years and over now take antidepressant medication.[14] Since the 1930s, anxiety and depression among young people in America have steadily increased.[15] The World Health Organization predicts that by 2020 depression will be the second most prevalent medical condition in the world.[16]

An amazing abundance of material goods, and so little happiness. Novelist and social observer James Baldwin claimed that Americans possess the “world’s highest standard of living and what is probably the world’s most bewildering empty way of life.”[17] Can anyone dispute that the “American way of life has failed to make people happier or to make them better?”[18] The entire project of capitalism has been realized, except its end, the happiness of humankind.

We have to look to a different culture to see that material goods can be used for other than physical comfort and an easier life. According to Chief Standing Bear, young Lakota children were taught to give: “When mothers gave food to the weak and old, they gave portions to their children at the same time, so that the children could perform the service of giving with their own hands.” Contrary to the ethic instilled by capitalism, “the greatest brave was he who could part with his most cherished belongings and at the same time sing songs of joy and praise.” The Lakota held “give-away-dances” to distribute presents that were costly and rare.[19]

Equality Equals Opportunity

The middle and the upper-middle class in America, in a real sense, live as the aristocrats did in the past. Why the descendants of the dregs of Europe who immigrated to America would live like the aristocrats of Old Europe was explained by Tocqueville in 1835. He encapsulated the results of his ten-month journey throughout the United States in the first sentence of Democracy in America: “No novelty in the United States struck me more vividly during my stay there than the equality of conditions.”[20] In America, a peasant or a person of low birth was not oppressed by the lord of the manor, a village priest, or an educated magistrate. As a result, the equality of conditions in America unleashed the great potential and talent hidden within each human being.

The middle and the upper-middle class in America, in a real sense, live as the aristocrats did in the past. Why the descendants of the dregs of Europe who immigrated to America would live like the aristocrats of Old Europe was explained by Tocqueville in 1835. He encapsulated the results of his ten-month journey throughout the United States in the first sentence of Democracy in America: “No novelty in the United States struck me more vividly during my stay there than the equality of conditions.”[20] In America, a peasant or a person of low birth was not oppressed by the lord of the manor, a village priest, or an educated magistrate. As a result, the equality of conditions in America unleashed the great potential and talent hidden within each human being.

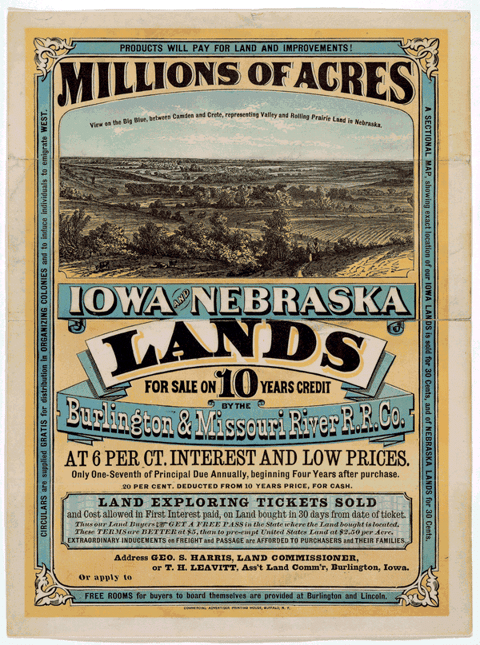

The first U.S. census conducted in 1790 revealed that about 80% of the white population was of British ancestry. The next two great waves of legal immigration would substantially change that figure. Because of the potato famine in Ireland (1845-1849), over one million Irish fled their homeland to escape poverty and death. In the 1850s, over 1,700,000 immigrants from Northern Europe came to America. Unsettled land was still plentiful and cheap in the mid-nineteenth century. (For a late nineteenth-century broadside advertisement offering cheap land in Iowa and Nebraska to immigrants, see illustration.[21]) Germans, Swedes, Norwegians, and Danes, some driven by failed revolutions in continental Europe, settled the Midwest.

After 1870, 25 million Europeans—mainly Italians, Greeks, Poles, Ukrainians, and Hungarians—flooded into America. In this third wave of immigration to the United States, Southern and Eastern Europeans flocked to cities. (See the illustration, Mulberry Street, along which Manhattan’s Little Italy is centered, circa 1900.[22])

After 1870, 25 million Europeans—mainly Italians, Greeks, Poles, Ukrainians, and Hungarians—flooded into America. In this third wave of immigration to the United States, Southern and Eastern Europeans flocked to cities. (See the illustration, Mulberry Street, along which Manhattan’s Little Italy is centered, circa 1900.[22])

The United States became known as the land of opportunity. Impoverished immigrants through hard work could accrue money, property, and social standing. Unlike Europe, the circumstances of birth were no barrier to the upper echelons of society or high political status. Children of immigrants became doctors, lawyers, and professors.

The steel, coal, automobile, textile, and garment industries were built upon the backs of the tired, poor, huddled masses yearning for a better life. Without cheap labor, without immigrants accustomed to hard work and suffering, yet, hopeful of a better life, the United States would not so quickly have become a world economic power.

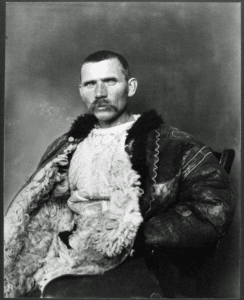

If my parents, Romanian gypsies, born in a Transylvanian village and raised in thatched-roofed houses with dirt floors, hadn’t heeded the inscription on the Statue of Liberty—“Give me your tired, your poor”—I would be a wandering Romanian gypsy, stealing chickens, telling fortunes, and evading taxes. (See illustration.[23])

If my parents, Romanian gypsies, born in a Transylvanian village and raised in thatched-roofed houses with dirt floors, hadn’t heeded the inscription on the Statue of Liberty—“Give me your tired, your poor”—I would be a wandering Romanian gypsy, stealing chickens, telling fortunes, and evading taxes. (See illustration.[23])

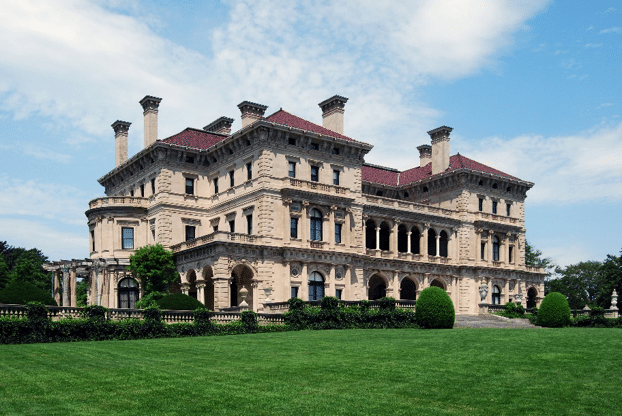

In the United States, the distribution of income has never approached anything like equality. Cornelius Vanderbilt II, between 1893 and 1895, built his Newport, Rhode Island summer home, The Breakers, a 70-room, 65,000 square foot mansion, at the cost of more than $7 million (approximately $215 million today when adjusted for inflation). For a rear view of The Breakers, see illustration.[24]

In 2017, Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, and Jeff Bezos collectively had more wealth than the bottom 160 million Americans.[25] Bezos, pre-divorce the richest American, would have to spend $28 million every day to keep his wealth from growing, while half of Amazon’s employees make less than $28,446 a year.[26] In 2019, the seven heirs to the Walmart fortune were worth $179 billion, making the Waltons the wealthiest family in America.[27] Should the economic well-being of the ordinary citizen to be measured by George Soros, the world’s wealthiest hedge fund manager with an estimated net worth of $25.2 billion, or by Ethan Martin, a sodbuster in Nebraska at the beginning of the twentieth century?

Most Americans are angered by the economic inequality in the United States. But nature distributes intelligence, bodily strength, and physical beauty unequally. Tocqueville held that “all conditions of life can never be perfectly equal,” because the inequality of talents comes “directly from God [and] will ever escape the laws of man.”[28] With his usual prescience, Tocqueville argued that “the more equal men are, the more insatiable will be their longing for equality.”[29]He prophesized that “Americans will never get the equality they long for. . . . [it] ever retreats before them without getting quite out of sight, and as it retreats it beckons them on to pursue.”[30] For us Americans, equality is like the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock, forever receding from us, yet always visible.

Most Americans are angered by the economic inequality in the United States. But nature distributes intelligence, bodily strength, and physical beauty unequally. Tocqueville held that “all conditions of life can never be perfectly equal,” because the inequality of talents comes “directly from God [and] will ever escape the laws of man.”[28] With his usual prescience, Tocqueville argued that “the more equal men are, the more insatiable will be their longing for equality.”[29]He prophesized that “Americans will never get the equality they long for. . . . [it] ever retreats before them without getting quite out of sight, and as it retreats it beckons them on to pursue.”[30] For us Americans, equality is like the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock, forever receding from us, yet always visible.

Individualism Equals Freedom

Tocqueville captured in one word the essence of Modernity. He was the first person to use the word “individualism” and reports “that word ‘individualism,’ which we coined for our own requirements, was unknown to our ancestors, for the good reason that in their days every individual necessarily belonged to a group and no one could regard himself as an isolated unit.”[31]

A new word, “individualism,” was needed to describe American life, because each new wave of immigrants to America wished in some way to throw off the shackles of tradition, custom, and authority, “to escape from imposed systems, the yoke of habit, family maxims, class prejudices, and to a certain extent national prejudices as well . . .”[32] First-generation Americans were more intent upon casting off the shackles of tradition and custom, to be freed from all authority, than their immigrant parents. Soon “each generation is a new people,” and the “woof of time is . . . broken and the track of past generations lost. Those who have gone before are easily forgotten, and no one gives a thought to those who will follow.”[33]

Today, except for grade school history, we Americans have no past, and except for anticipation of new consumer goods, we have no future. Most of us are isolated, autonomous creatures, alone in an indifferent world.

The 2000 U.S. census uncovered that one out of every four households consisted of only one person. “At any given time, roughly twenty percent of individuals—that would be sixty million people in the U.S. alone—feel sufficiently isolated for it to be a major source of unhappiness in their lives,” write John Cacioppo, a research psychologist at the University of Chicago, and William Patrick, the editor of the Journal of Life Sciences.[34] Vice Admiral Vivek H. Murthy, the Surgeon General of the United States from 2014 to 2017, observed that “loneliness and weak social connections are associated with a reduction in lifespan similar to that caused by smoking 15 cigarettes a day and even greater than that associated with obesity, [as well as with] a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, depression, and anxiety.”[35]

Loneliness, the desolate, empty feeling of being deprived of human companionship, is an inescapable consequence of individualism. We move away from our families, do not know our neighbors, and get accustomed to walking down the same crowded streets every day without looking anyone in the eye.

Eerily, Tocqueville’s worst fear about what awaited America in the future seems fulfilled: “an innumerable multitude of men, all equal and alike, constantly circling around in pursuit of the petty and banal pleasures with which they glut their souls. Each of them, withdrawn into himself, is almost unaware of the fate of the rest. Mankind, for him, consists in his children and his personal friends. As for the rest of his fellow citizens, they are near enough, but he does not notice them. He touches them but feels nothing. He exists in himself and for himself . . .”[36]

Yet, in the back of our minds, we know that in other times, people touched one another and felt the joy of social living. Lakota Chief Standing Bear describes a Native American’s relation to the world before the Europeans arrived in the New World: “There was no such thing as emptiness in the world. Everywhere there was life, visible and invisible . . . Even without human companionship one was never alone. The world teemed with life and wisdom.”[37] In solitude, a Lakota experienced a profound connection to nature and to the Great Mystery.

Unlike the Lakota, no matter where we are, even when in a familiar group, we Americans always feel a vague sense of estrangement and loneliness. Many popular songs express the aching pain and empty feeling of social isolation. You feel more alone with more people around, Bob Dylan agonizes.[38] “Where do all the lonely people come from?” the Beatles ask.[39] In 2008, with the financial markets near collapse, Dutch photographer Reinier Gerritsen went down in the New York City subway system to capture the mood of commuters.[40] He found subjects filled with sadness and despair. Almost no one was smiling. Loneliness in America is epidemic.

We Americans are pursuing two green lights—equality and individualism—that are contradictory: I want to be equal to you in every regard; however, I strive to surpass you at academics, on the playing field, and in the workplace. Filled with confidence, each of us takes pride in our independence and believes that we can make the world conform to our desires, until we realize that the mass of our fellow citizens is competing against us. Then, we fully experience that no individual is obligated to use his talents and energy for another and that no one can legitimately claim substantial support from his fellow citizens, for like him, “they are both impotent and cold.”[41]

Because of our isolation from our neighbors and of our individual weakness, we need and desire a strong central government as the “sole and necessary support”[42] if economic disaster befalls us. The Great Recession of 2008 was devastating for low-income Americans. Just consider one story among hundreds of thousands. Samantha, 40, of Randolph, Vermont, had a full-time job as a bank receptionist, but it did not cover her basic living expenses. She felt like she had slipped from the middle class. “I am a single mom of two children. My son is nine years old and has special needs . . . and my daughter is six. I work 40 hours a week as a receptionist at a bank. I get paid $11 an hour. I cashed in an IRA last year to help pay for my home. My mortgage is $75,000, yet between heating costs (and I get fuel assistance), property taxes, and my water bill, garbage bill, plowing bill, I am not making enough money to pay my bills. I have an associate’s degree and had the same kind of job twelve years ago on Long Island in New York. I am making less now, yet food and gas and home heating oil prices and other costs have risen drastically. I was a stay-at-home mom for six years, but went back to work after my divorce. . . . I have very little money in savings and my car is getting older and cannot afford a car payment.”[43] Without such federal programs as unemployment compensation, worker re-training programs, food stamps, and fuel oil assistance, many would as an aftereffect of the Great Recession of 2008 have sunk into extreme poverty, living on the streets or in their cars.

Equality gives Americans the “habit and the taste to follow nobody’s will but their own in their private affairs. . . . and makes them suspicious of all authority,”[44] but individualism forces them to accept, even demand, a strong central government. In the end, political liberty, the exercise of self-government in local, state, and national public meetings, becomes replaced by personal freedom, the capability to do as one wishes, unrestrained by others, and thus many Americans believe they have captured the green light, thinking individualism equals freedom. But writer David Foster Wallace claims that personal freedom is “the freedom to be lords of our own tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the center of all creation.”[45]

What to Do

Many, if not most of us, are like Gatsby trying to incarnate his romantic vision of life with Daisy, and thus are incapable of not pursuing the green light, believing prosperity will make us happy, hoping perfect equality is attainable, and thinking freedom means the absence of social obligation. Like Gatsby, if we pursue the impossible, we will come to a bad end, not that we will be murdered as Gatsby was, but frustration, anger, and bitterness with life itself awaits us. To avoid personal as well as communal tragedy, we need a better understanding of happiness, equality, and freedom.

From the standpoint of the Western tradition anchored in Athens and Jerusalem, we Americans have embraced a mistaken notion of freedom. For Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Jesus, truth is primary, not freedom, and one inherent danger in human life is to forsake reason and become a slave of the passions. The good life consists in the “active exercise of the soul’s faculties in conformity to rational principle,”[46] which is Aristotle’s way of saying that for a person to be happy, the passions must be directed by reason. Courage frees us from slavery to fear, generosity from slavery to hunger for money, and temperance from slavery to drugs, alcohol, and sexual lust. Without freedom, we could not acquire good habits or replace bad habits with good ones, and thus would be condemned to a life of slavery. Self-mastery is the mark of a free person, not the “license to do whatever one wants.”[47]

Equality is the founding principle of the United States of America, as seen in the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the Declaration, held “there is a natural aristocracy among men,” based on “virtue and talents.” Jefferson also acknowledged the existence of an “artificial aristocracy founded on wealth and birth, without either virtue or talents.” He thought that the natural aristocracy was a “most precious gift of nature” for the governance of society, while the artificial aristocracy was a “mischievous ingredient in government.” He maintained that state and federal constitutions prevented the ascendancy of the artificial aristocracy, for the citizens in free elections would separate the “wheat from the chaff.”[48]

To ensure a large natural aristocracy to run the American democratic governments, Jefferson proposed legislation for a “more general diffusion of learning.” He offered a plan for free education from grade school to university under a system that would seek out those of “worth and genius” from “every condition of life” and prepare them for “defeating the competition of wealth and birth” for public life.[49]

In the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson begins the argument for the separation of the thirteen united States of America from the British Empire with the premise that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” Implicit in this premise is that that the origin of equality lies in the Hebrew Bible: “God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.”[50] Jefferson subtly shifted what Christians traditionally called “human dignity” possessed by everyone to universal equality, a political ideal.

John Lewis, civil rights leader, congressman, and ordained Baptist minister, in his farewell address to America, published on the day of his funeral, praised the millions of people “around the country and the world [who] set aside race, class, age, language and nationality to demand respect for human dignity.”[51] With his Christian understanding of the human person, Lewis carefully avoided the word “equality.” Acknowledging the human dignity of the other requires a change of heart, while the pursuit of equality demands unending new laws.

The Christian understanding of inequality is that God unequally bestows gifts that are to be used for the common good; everyone receives at least one talent, so he or she can contribute to the commonweal. The wise can guide others; the intelligent can uncover the secrets hidden in nature; the well-organized can administer businesses that provide employment; the strong can protect the weak.[52]

For a few of us, the green light prosperity equals happiness has gone out, and for direction, we return to what Fitzgerald took to be the tragedy of America, the rejection of the “aesthetic contemplation” of nature in favor of material wealth: The Dutch sailors neither understood nor desired the wonder aroused by the “fresh, green breast of the new world.”[53] Gone forever is the experience of a pristine continent; yet, every person as a young child awakens to the wonder and mystery of a new world, to the source of poetry and philosophy. Some of us as adults still wonder how birds fly, why the trees turn color in the fall, or how ants find their way back home. If a person is truly alive, then everything in nature evokes wonder, especially the human being, the strangest creature of all, whose three-pound brain, shaped like a giant wrinkled walnut, in some mysterious way can grasp all Creation.

Endnotes

[1] F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Collier Books, 1980 [1925]), p. 94

[2] Ibid., p. 182.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Harper & Row, 1966 [1835, 1840]), p. 485.

[6] Perry Miller gave a brilliant presentation of the Puritan economic outlook in an address delivered at the Annual of the Unitarian Ministerial Union, held at King’s Chapel, Boston, May 18, 1942. See “Individualism and the New England Tradition” in The Responsibility of Mind in a Civilization of Machines: Essays by Perry Miller, ed. John Crowell and Stanford J. Searl, Jr. (Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1979.)

[7] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 11.

[8] Francis Bacon, The New Organon: Or the True Directions Concerning the Interpretation of Nature (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1960 [1620]), p. 103.

[9] National Poverty Center, Extreme Poverty in the United States, 1996 to 2011.

[10] Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century.

[11] See Robert E. Lane, The Loss of Happiness in Market Democracies (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 2001), p. 5.

[12] Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (August 4, 2010) 107 (38): 16489–16493.

[13] Cross-National Collaborative Group, “The Changing Rate of Major Depression,” Journal of the American Medical Association (December 2, 1992) 268 (21): 3098-105.

[14] NCHS Data Brief, Antidepressant Use in Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2005–2008.

[15] Jean M. Twenge, Brittany Gentile, Nathan DeWall, Debbie Ma, Katharine Lacefield, and David R. Schurtz, “Birth Cohort Increases in Psychopathology Among Young Americans, 1938–2007: A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis of the MMPI,” Clinical Psychology Review 30 (2010): 145-154.

[16] World Health Organization, Mental Health: A Call for Action by World Health Ministers.

[17] James Baldwin, “Mass Culture and the Creative Artist: Some Personal Notes,” Daedalus, 89, No. 2 (Spring 1960): 374.

[18] Ibid., p. 375.

[19] Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978), pp. 14-15.

[20] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 9.

[21] Library of Congress: An American Time Capsule.

[22] Wikimedia Commons from United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3g04637.

[23] Augustus Francis Sherman, Romanian Shepherd, Ellis Island, circa 1906. Public Domain, copyright expired, Wikimedia Commons.

[24] Matt H. Wade, CC-BY-Sa-3.0, Wikimedia Commons.

[25] Noah Kirsch, “The Three Richest Americans Hold More Wealth Than Bottom 50% of the Country, Study Finds,” Forbes (November 9, 2017).

[26] Annie Lowrey, “Jeff Bezos’s $150 Billion Fortune Is a Policy Failure,” The Atlantic (Aug. 1, 2018).

[27] See Walton Family, Wikipedia.

[28] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, pp. 537, 538.

[29] Ibid., p. 538.

[30] Ibid.

[31]Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Régime and the French Revolution, trans. Stuart Gilbert (New York: Doubleday, 1955 [1856]), p. 96.

[32] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 429.

[33] Ibid., pp. 473, 507.

[34] John Cacioppo and William Patrick, Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection (New York: Norton, 2009), p. 5.

[35] Vivek H. Murthy, “Work and the Loneliness Epidemic,” Harvard Business Review (Sept. 27, 2017).

[36] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, pp. 691-692. Italics added.

[37] Standing Bear, p. 14.

[38] See Bob Dylan, “Marchin’ to the City,”on the album Tell Tale Signs: the Bootleg Series Vol. 8.

[39] See The Beatles, “Eleanor Rigby” on the album Revolver.

[40] See “Alone Together,” The New York Times Magazine (April 3, 2011), pp. 45-47.

[41] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 672.

[42] Ibid.

[43] For more recession stories, see “Struggling through the Recession: Letters from Vermont.” Available https://www.sanders.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/recessionstories3.pdf.

[44] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 667

[45] David Foster Wallace, Kenyon College Commencement Address, 2005. Available http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122178211966454607.html#articleTabs%3Darticle.

[46] Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics, trans. Martin Ostwald (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1962), Bk. I, line 1098a7.

[47] Plato, Republic, trans. Paul Shorey, in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961), Bk, VIII, 557b.

[48] Thomas Jefferson, Letter to John Adams, 28 Oct. 1813. Available http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch15s61.html.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Genesis 1:27. RSV

[51] John Lewis, “Together, You Can Redeem the Soul of Our Nation,” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/30/opinion/john-lewis-civil-rights-america.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article.

[52] See Romans 12:6-8.

[53] Fitzgerald, p. 182.