|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

Chronic Pain and Two Great Lessons from John E. Sarno, M.D.

1981 was a pivotal year for the treatment of chronic pain. In that year, Dr. John E. Sarno, a rehabilitation physician at New York University, published Healing Back Pain: The Mind-Body Connection that became a best seller. Sarno proclaimed that chronic pain is caused by repressed emotions, especially anger. To distract the sufferer from anger, anxiety, and feeling of inferiority, the brain creates pain in the back, neck, or shoulder by decreasing the blood flow to muscles and nerves, resulting in oxygen deprivation that causes pain.

The medical community mainly ignored or maligned Sarno; privately, many of his peers dismissed him as a quack. To use a highfalutin philosophical term, the medical community judged Sarno’s theory of pain as horseshit. However, the devoted readers of Healing Back Pain considered Sarno a saint. They scribbled away in journals to purge their repressed negative emotions and were cured. When Larry David (Curb Your Enthusiasm and Seinfeld) heard Sarno say, “No herniated disc. There’s nothing wrong with you,” David said, “All of a sudden, the pain was gone. It was the closest thing I’ve ever had in my life to a religious experience, and I wept.”[1]

Probably because the amygdalae of medical practitioners are attuned to the negative and diminish the positive, the two insightful pronouncements of Sarno went unheard until recently. One: Chronic pain is not caused by tissue damage, which is why the traditional Western medical treatment, surgery and analgesics, fails. Two: Patients should resume their usual physical activity; walking or riding a bike will not injure them.

Another great lesson to be learned from Sarno is not that he was a miscreant, peddling nonsense to a misguided public. Instead, the hypothesized cause of a disease and the proposed treatment are often two separate assertions, as much as we desire them to be logically connected through cause and effect. The treatment can be effective, and the hypothesized cause of the disease nonsense.

Consider David C. Roberts, a Ph.D.in physics, working as a U.S. diplomat in Thailand. Unexplained pain racked his back and joints; he stood during meetings, avoided plane travel, and took motorcycle taxis to go less than a block. The doctors at the embassy deemed him unfit for work and medevacked him from Bangkok back to the United States for treatment at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where the doctors found no physical cause for his chronic pain. Roberts said, “I joined the other no-hopers at Mayo’s Pain Rehabilitation Center. There, chronic pain, unlike the acute variety, was treated as a malfunction in perception . . . The brain becomes addicted to dramatizing pain, they said; and the more you feed it, the stronger the addiction. So don’t dwell on the pain, and don’t try to fix it — no props, no pills. Eventually, the mind should let go.”[2]

Despite his reluctance, and maybe because of his despair, he tried one of the clinic’s suggestions: meditation that he previously called “new age hooey.” He made meditation a daily ritual. Two months of meditation changed his relationship with his chronic pain. He noticed that sensations, not pain, rose and fell. On several occasions, the chronic pain occurred with great intensity, but he did not “try to attack or run, and it didn’t bark or bite back; we simply eyed each other warily.”

Not quite after three years of meditation, Roberts said, “I not only look the part of a healthy man but manage to act it too: hiking Great Gable in the Lake District and neighborhood-hopping around New York City, though admittedly I tend toward yoga, swimming, and epic walks rather than the macho sports of my youth.”

The Mayo Clinic treatment of chronic pain had two parts: 1) A story told in scientific terms about the cause of chronic pain, and 2) A seeming woo-woo treatment that had no logical or causal connection to science. To trust their doctors and to accept an unorthodox treatment, patients in our materialistic culture need to hear a scientific story explaining their chronic pain in terms of brain function; the storytelling works best when the physicians are ardent believers.

Neither the Mayo Clinic nor the Sarno treatments were rigorously evaluated by impartial researchers; the successes were always what physicians call anecdotal. Recently, Pain Reprocessing Theory, a new therapy for chronic pain advocated by Alan Gordon, Founder and Director of the Pain Psychology Center in Los Angeles, underwent an extensive scientific evaluation.

Gordon argues in his book, The Way Out: A Revolutionary, Scientifically Proven Approach to Healing Chronic Pain, that when the body experiences an injury, the brain generates the feeling of pain. Acute pain is caused by damage to the body, but sometimes the “pain switch” in the brain gets stuck in the on position, which causes chronic pain, or what Gordon calls “neuroplastic pain.”[3] When this happens, “the brain is misinterpreting normal messages from the body as if they were dangerous. The body is fine, but the brain creates pain anyway. In other words, neuroplastic pain is a false alarm.”[4]

The key to understanding neuroplastic pain is fear. Major life changes, both positive and negative, in a person’s life are often stressful and put the brain on high alert, which changes the way a person perceives signals from her body; what was once ignored by the brain is now reported as intense pain. For other sufferers from chronic pain, everyday stress is not that important, while habits from the past, usually stemming from adverse childhood experiences, such as a “troubled family dynamic, struggling in school, or being bullied,” make them prone to fear.[5]

Many sufferers of chronic pain are caught in a feedback loop: Pain triggers feelings of fear; the fear puts the brain on high alert, which causes more pain, which leads to more fear, and on it goes.

For Gordon, the cause of neuroplastic pain is fear, an umbrella term for him that includes “frustration, despair, stress, anguish, anxiety, annoyance, dismay, and anything else that puts [a person] on high alert.”[6] The claim of Pain Reprocessing Therapy (PRT) is that when the fear goes away, soon after, the pain fades. PRT is a way of investigating pain without fear through somatic tracking, a technique similar to mindfulness meditation, defined by Jon Kabat-Zinn, who popularized mindfulness in the West, as “paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally.”[7]

Somatic tracking is designed to reduce feelings of danger and foster a sense of safety in a chronic pain sufferer. The word “pain” is replaced by “sensations,” and safety reappraisal reminds the brain that these sensations are not dangerous.

Here is an example of somatic tracking from Gordon:

You may find it helpful to close your eyes during somatic tracking to make it easier to focus on your inner sensations. . . . What I’d like you to try, for just a few moments, is to bring your attention to the sensation of pain wherever you feel it in your body. As you explore your pain, the first thing I’d like you to do is identify the quality of the sensation. What does it feel like? Is it a tight sensation? A burning sensation? A tingling sensation? Take a few moments to check it out. Once you’ve identified the quality of the sensation, explore it a little. Is it widespread, or is it localized? Does it feel the same everywhere, or is it stronger in some spots than others? As you start to get the lay of the land, simply observe the sensation. You don’t need to get rid of it, you don’t need to change it — all you need to do is watch, noticing and exploring from a place of lightness and curiosity. . . .

As you pay attention to the sensation in your body, what do you notice? Does it intensify? Does it subside? Does it change in quality? Does it move around? Whatever it does is okay. Remember, this is a safe sensation. It’s simply your brain misinterpreting safe messages that are coming from your body. So just sit back and enjoy the show.[8]

An actual full session of pain reprocessing therapy (PRT) delivered by Alan Gordon is given here.

And now, for the subtitle of Gordon’s book; PRT is “scientifically proven.” Between 2017 and 2020, 151 individuals with low to moderate back pain were recruited from the community of Boulder, Colorado for a randomized clinical trial. A third of the participants received no treatment other than their usual care (the control group), a third got a placebo, and a third had eight one-hour sessions of pain reprocessing therapy. The study found that PRT yielded large reductions in chronic back pain intensity relative to the placebo and usual care control conditions; nearly two-thirds of patients receiving PRT were pain-free or nearly pain-free at posttreatment, compared to ten percent of the control group and twenty percent of the placebo group. Large effects of PRT on pain were seen at the one-year follow-up, with slightly over half of the PRT recipients either pain-free or nearly pain-free.[9]

This is good news for most patients, for if chronic pain is learned, it can be unlearned. For other patients, the scientific confirmation of PRT is bad news, for pain management requires work and commitment, not the desired quick cure through pills or the surgeon’s knife.

The numbers from this study are impressive, especially since PRT patients were given only eight one-hour sessions. Unlike John Sarno and the practitioners at Mayo Clinic Pain Rehabilitation Center, Alan Gordon found a more effective way of quieting a patient’s fear, reducing her pain, and getting her moving again almost immediately.[10] He should be commended.

That our internal map of pain can be changed suggests that our internal maps of who we are and what the world is, often drawn from adverse childhood experiences, can also be redrawn.

Changing Internal Maps to Conform to the Territory

As we saw, Alan Gordon argued that chronic pain results when the “pain switch” in the brain gets stuck in the on position. He discovered that somatic tracking turns the pain switch off. Another way to accomplish the same result is Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT), generally called “Tapping.”

Everything in mind/body medicine seems to begin with an accident that leads to the unorthodox. In 1980, psychologist Roger Callahan had a patient Mary, who suffered from a phobia of water. Mary’s fear of water controlled her life and kept her from such daily activities as taking her children to the beach or even driving near the ocean. She grew fearful when it rained and had vivid nightmares involving water.[11]

Using conventional psychotherapy, Callahan treated Mary for more than a year with little success. She had learned to cope with the intense fear and emotional pain of her phobia but had not conquered her fear of water. She could sit within sight of the pool at Callahan’s house; however, the nearness to the pool caused her stomach pains.

Callahan had recently been studying traditional Chinese medicine and studying the effect of tapping on acupuncture points located along meridians of the body. Suddenly he had an inspiration. Remembering an acupuncture point for the stomach meridian on the cheekbone, he asked Mary to tap there, thinking it might cure her stomach pains.

Mary tapped her cheekbone as directed, and the response to this slight action was miraculous. Her stomach pains disappeared; even more amazingly, her phobia of water vanished. She ran down to the pool and began splashing herself with water, rejoicing in her newfound freedom from fear.

Based on this accidental discovery, Callahan began a series of investigations to develop and refine tapping on acupuncture points. A student of his, Gary Craig, simplified the complex system that Callahan created and is credited with founding EFT in the late 1990s with the publication of his The EFT Manual.

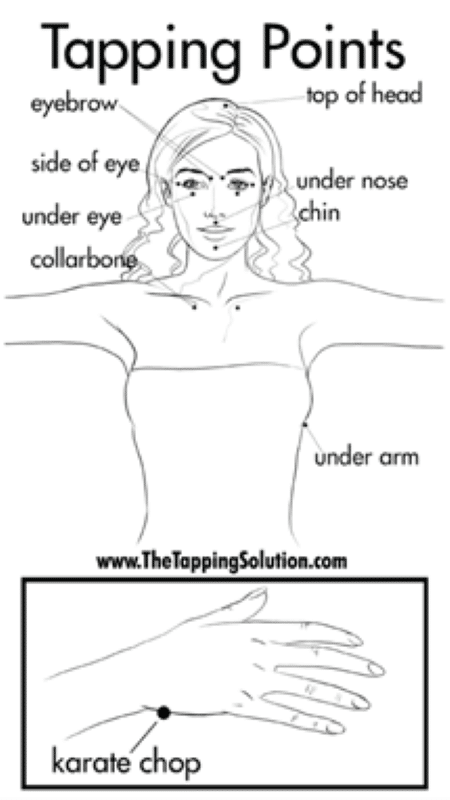

The tapping points are shown in the illustration. That tapping on a few acupressure points can relieve anxiety or chronic pain seems weird, if not downright New Age woo-woo, especially when its validity is given in terms of ch’i, the vital energy that animates any living entity, according to ancient Chinese medicine. When the flow of ch’i is impeded, sickness results; tapping on certain acupressure points releases ch’i and restores the body to health.

Today, how Tapping works is told in terms of a scientific story that begins with the amygdala, the threat detection part of the brain. While tapping on the karate chop point, a person mentally recalls the traumatic memory that puts the amygdala into the threat response mode. This setup instantly approximates the brain state the person was in during the traumatic event, if only to a slight degree. When the threat response has gone up, then the person sends a different signal by tapping on the other acupuncture points that decrease the threat response, so now the brain is getting two opposed signals: 1) The memory is increasing the amygdala threat response, and 2) The tapping is decreasing the threat response. With the amygdala receiving these two opposed signals, the signal that decreases arousal begins to predominate. The result is that the person still has the memory, but the associated threat response does not reoccur. The emotional component of the memory is significantly weakened and ideally eliminated altogether. In this way, a person is no longer controlled by a traumatic memory.[12]

Here is an abbreviated tapping session given by Nik Ortner, the author of The Tapping Solution: A Revolutionary System for Stress-Free Living and creator of the Tapping Solution App.

We’re starting to tap on the side of the hand, called the karate chop point. It’s below the pinky on the outside of the hand. Take four fingers of one hand and tapping gently; use whatever hand feels comfortable. Tune into your breath and repeat after me, even though I feel so much anxiety about everything that’s going on, I choose to relax and feel safe. And we’re still on the side of the hand, tapping gently, even though this feels so overwhelming, I choose to relax and feel safe. And one more time, still tapping on the side of the hand, even though I’m holding so much stress in my body, it’s safe to let it go.

Now, we’ll tap through the other acupressure points. The first point is the eyebrow, where the hair meets the nose. You can use two fingers of one hand, or tap on both eyebrow points with each hand, for the meridians run down both sides of the body. Just tap gently and tune in to the stress and anxiety. All we’re doing this moment is we’re looking to fire that amygdala because we want to counteract it with a calming signal.

Keep tapping gently and breathing gently. Now we’ll move to the side of the eye. It’s not at the temple but a little further in, right on the bone again, one side or both sides of the face. Don’t worry about getting it perfect. Take a moment to think about just how overwhelmed you are, to feel how swamped you are.

Now we begin to send the calming signal to the amygdala. Tap under the eye, right on the bone. It’s safe to feel this anxiety. Tap under the nose. It’s safe to begin to let it go. Tap on the collarbone point; feel for the two little bones of the collarbone, just go about an inch right below them. You can tap, tap with all ten fingers of both hands. It’s safe to feel this anxiety. Tap underneath the arm, three inches underneath the armpit, either side of the body, right on the bra line for women. It’s safe to feel all the stress. Tap on the top of the head. It’s safe to let it go.

Moving back to the eyebrow. It’s safe to breathe deeply. It’s safe to breathe deeply. Side of the eye. I acknowledge all my stress. I acknowledge all my stress. Under the eye. I begin to feel safe in my body. I begin to feel safe in my body. Under the nose. The more I relax, the more I relax (Under the mouth.) the more my body heals. The more my body heals. Collarbone. The more I relax, the more I relax (Under the arm.), the more my body heals. The more my body heals (Top of the head.), letting go now, letting go now. And you can gently stop tapping and take a breath in and let it go.

These two very quick rounds were for demonstration. Many of the meditations on our app are anywhere between eight and twelve minutes in order to go a little bit deeper. What happens with the tapping process is that we think we’re worried about one thing, but suddenly, we realize it’s really this other thing that we’re worried about. Our unconscious mind gives us the truth about what we’re feeling, what’s really happening inside of us, and helps us to let go.[13]

Tapping seems to have widespread application to many mind/body disorders. Peta Stapleton and her colleagues published “Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) Improves Multiple Physiological Markers of Health” in the Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine, a report on a tapping study with 203 participants enrolled in 4-day training workshops. “Significant declines were found in anxiety (−40%), depression (−35%), posttraumatic stress disorder (−32%), pain (−57%), and cravings (−74%).” The researchers concluded that “reviews and meta-analyses of EFT demonstrate that it is an evidence-based practice and that its efficacy for anxiety, depression, phobias, and PTSD is well-established.”[14]

Dawson Church, former President of National Institute of Integrative Medicine, was a leader in using Tapping to treat veterans suffering from PTSD.

Estimates of PTSD prevalence rates among returning service members vary widely. In one major study of 60,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, thirteen percent of deployed and nondeployed veterans screened positive for PTSD, while other studies show the rate to be as high as twenty to thirty percent. As many as 500,000 U.S. troops who served in these wars from 2003 to 2016 have been diagnosed with PTSD.[15] The documentary film OPERATION: Emotional Freedom — The Answer shows the successful treatment of PTSD through Tapping; a short excerpt from the documentary is given in the accompanying video.

Many veterans with PTSD resist treatment. For example, one of Kolk’s patient, Tom a platoon leader in Vietnam, suffered from nightmares ten years after his service in ‘Nam. “His sleep was constantly interrupted by nightmares about an ambush in a rice paddy back in ’Nam, in which all the members of his platoon were killed or wounded. He also had terrifying flashbacks in which he saw dead Vietnamese children.”[16] Kolk prescribed a drug that was effective in reducing the incidence and severity of nightmares.

Two weeks later, in his follow-up appointment, Tom told Kolk that he did not take the medication. Kolk, trying to conceal his irritation, asked why. Tom explained, “I realized that if I take the pills and the nightmares go away. I will have abandoned my friends, and their deaths will have been in vain. I need to be a living memorial to my friends who died in Vietnam.”[17]

Many veterans suffering from PTSD hate themselves for the atrocities they committed. The day after the ambush of his platoon, Tom went into a frenzy in a neighboring village, killing children, shooting an innocent farmer, and raping a Vietnamese woman. To avoid confronting his demons, Tom worked like crazy in his law office during the week and drank and drugged on the weekends. Self-hatred is extraordinarily difficult to overcome and unfortunately is very common, as the ACE Study discovered.

Consider Katie, a patient of Alex Howard, the Founder of The Optimum Health Clinic and Conscious Life. Katie complained of depression, lack of motivation, and loneliness. She said, “I’ve been craving all my life to be loved and nurtured and cherished. I don’t know what it feels like to be unconditionally loved and to be the most important thing in somebody else’s eyes. I always felt unlovable.”[18]

Alex told Katie, “I think part of the reason why that’s so painful is because of the emotional neglect that you experienced as a child.”

A local firm sought Katie for a new job. She was shortlisted, interviewed, and offered the job. The same day she accepted the position, one of the campaigns she ran the previous year was nominated for an award. Instead of being elated over her new job and the nomination, her response to the good news was “Why am I doing this? You know, it’s all about seeking validation to prove to the world that I’m good enough, but it’s a big, big, big load of shit; I’m really none of those things. I want to just be me, but like I said, at the beginning, I don’t even know who Me is.”

Katie is caught in a double bind. From her adverse childhood experience, she concluded she was unlovable, which may have served her well as a child but not as an adult. Her success in the workplace earned her praise and commendations, not the unconditional love she yearned. But to give up her identity as an unlovable wretch would require her to enter the scary domain of not knowing who she is. As much as Katie hates her life, it is not as painful as having no identity, free-floating in a void.

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh taught that “people have a hard time letting go of their suffering. Out of a fear of the unknown, they prefer suffering that is familiar[19]

The treatment of self-hatred, a mind/body disease, necessarily brings us to seek an answer to the question, “Who am I?”

[Next episode: We Are Not Our Memories]

Main image courtesy of Deniz Altindas and Upsplash.

Endnotes

[1] See the movie, All the Rage (Saved by Sarno), directed by David Beilinson, Michael Galinsky, and Suki Hawley.

[2] David C. Roberts, “The Secret Life of Pain,” New York Times, Aug. 1, 2017.

[3] Alan Gordon with Alon Ziv, The Way Out: A Revolutionary, Scientifically Proven Approach to Healing Chronic Pain (New York: Avery, 2012), p. 5.

[4] Ibid., p. 24.

[5] Ibid., p. 36.

[6] Ibid., p. 44.

[7] Jon Kabat-Zinn, quoted by Gordon and Ziv, The Way Out, p. 67.

[8] Gordon with Alon Ziv, The Way Out, pp. 70-71.

[9] Yoni K. Ashar, Alan Gordon, Howard Schubiner, et al, “Effect of Pain Reprocessing Therapy vs Placebo and Usual Care for Patients with Chronic Back Pain,” JAMA Psychiatry, published online September 29, 2021.

[10] We do wish to belabor in the text that the study Ashar et al conducted confirmed the effectiveness of PRT not the scientific storytelling that is necessary in our materialistic culture and that such storytelling violates the principle of undivided wholeness.

[11] Nik Ortner, What Is Tapping and How Can I Start Using It?

[12] In the text, the term “traumatic memory” is used in common speech, not in the technical manner employed by psychiatrists such as Bessel van der Kolk: “Traumatic memories are fundamentally different from the stories we tell about the past. They are dissociated: The different sensations that entered the brain at the time of the trauma are not properly assembled into a story, a piece of autobiography.” (Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score, p. 136.)

[13] The text is an edited version of Nick Ortner’s Tapping Technique to Calm Anxiety & Stress in 3 Minutes.

[14] Donna Bach, Gary Groesbeck, Peta Stapleton, Rebecca Sims, Katharina Blickheuser, and Dawson Church, “Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) Improves Multiple Physiological Markers of Health,” Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine (published online February 19, 2019).

[15] Miriam Reisman, PTSD Treatment for Veterans: What’s Working, What’s New, and What’s Next.

[16] Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (New York: Penguin, 2015), p. 8.

[17] Ibid., p. 10. Kolk does not report in The Body Keeps the Score the outcome of Tom’s treatment for trauma.

[18] Rediscover who you are | Katie #2 | In Therapy with Alex Howard and How to shift a NEGATIVE STATE | In Therapy with Alex Howard.

[19] Thich Nhat Hanh, Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life (New York: Bantam Books, 1991).

2 Responses

Thank you, Dr Stanciu, for sharing this information. With no job and no income, I’m glad to know of something I can do on my own with the guidance of the text (EFT, and to some degree, PRT). I would be grateful to know of any other self-help available. God bless you, Dr Stanciu, for your efforts!

Hi Laura—

Excuse my tardy response to your request, but my wife was hospitalized for over a week and discharged yesterday afternoon—another nightmare. There are many excellent doctors and nurses, but all are working in an insane system of medical care.

Here is what I suggest. Go to YouTube; search for Robert Smith, tapping; pick one of his videos that look interesting to you, or in the search add a term that is of particular interest to you, maybe childhood memories, addictions, or trauma.

Let me know if you cannot find anything of interest, and I will search for you.

Peace and Love,

George