|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

Has Deep Gloom Killed the Future?

Before the Covid-19 Experiment focused our attention on not dying prematurely, most of us were enveloped in deep gloom, whose sources are still present. The two major political factions, the Left and the Right, promulgate apocalyptic images of the future that portray that we are fearfully close to a final descent into darkness; The human species is threatened by climate change; Kim Jong-un and Donald J. Trump can initiate nuclear war with the push of a button; the United States, China, and Russia are divvying up the globe and such contests between Nation-States to establish spheres of economic interest and political power always end in catastrophic wars; the shrinking middle class in America portends a society of the wealthy, the professionals, and a large underclass, a formula for political disaster. Hopelessness oozes forth from the New York Times and the National Review, from MSNBC and Fox News.

The prevailing sentiment in America is that nothing works. Health care, education, religion, race relations, law enforcement, and the media are broken and will never be fixed. Civility and communal values, once the bedrock of American life, are gone and not recoverable.

If we limit ourselves to the 24-hour news cycle, the urge to fire a bullet through one’s brain becomes nearly overwhelming. For us Americans, the Great Recession of 2008 is ancient history, as are the presidency of Barack Obama and Iraq War I; however, a broad historical perspective reveals that the confusion, anguish, and despair we experience is the result of living in a major transition of human history.

Modernity

We must not forget that Modernity is a recent invention of Western Europe, whose origin for our purposes can be precisely dated: In October 1620, Francis Bacon (1561–1626), one of the principal architects of modern science announced in one sentence the heart of the experimental method, something entirely new to mankind: “The office of the sense shall be only to judge of the experiment, and the experiment itself shall judge of the thing.”[1] Said another way, the scientist touches the experiment, and the experiment touches nature.

The introduction of experiment was a phase change in history, akin to the melting of ice into water, each substance with its own distinct properties. Prior to Bacon’s announcement, scientists, except for Galileo, followed Aristotle by passively observing nature; after Bacon, the goal of science was to “command nature in action,”[2] for “those twin objects, human knowledge and human power, do really meet in one; and it is from ignorance of causes that operation fails.”[3]

But experiment alone was not sufficient for a new science. René Descartes (1629–1649) furnished two key elements to direct the experimental investigation of nature. He held that to know nature was to know it mathematically and reasoned mechanics was mathematical, therefore if the universe was intelligible, “the laws of mechanics are identical with those of nature,”[4] and the mechanical universe was born. The second key element that Descartes introduced, now known as Cartesian reductionism, was the rule to commence “with objects that were the most simple and easy to understand, in order to rise little by little, or by degrees, to a knowledge of the most complex.”[5] The current version of Cartesian reductionism is “the universe, including our own existence, can be explained by the interactions of little bits of matter,”[6] a view widely held by physicists and neuroscientists.

That a “great mass of inventions”[7] would flow forth from experimental science is abundantly clear to us in the twenty-first century. Before 1620, the year Bacon argued in The New Organon for founding science on experiment, the number of inventions was meager. The significant inventions in sixteenth-century Europe were the pocket watch, bottled beer, and the Mercator map projection. The century in which Newton died, the eighteenth, science and technology lead to inventions that would transform society, such as the Franklin stove, gaslighting, the Watt steam engine, the cotton gin, the flying shuttle, and smallpox vaccination. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries inventions are so numerous they are cataloged by decades. The 1920s saw television, aerosol spray, sliced bread, and the extraction of insulin from animals for the treatment of diabetes.[8]

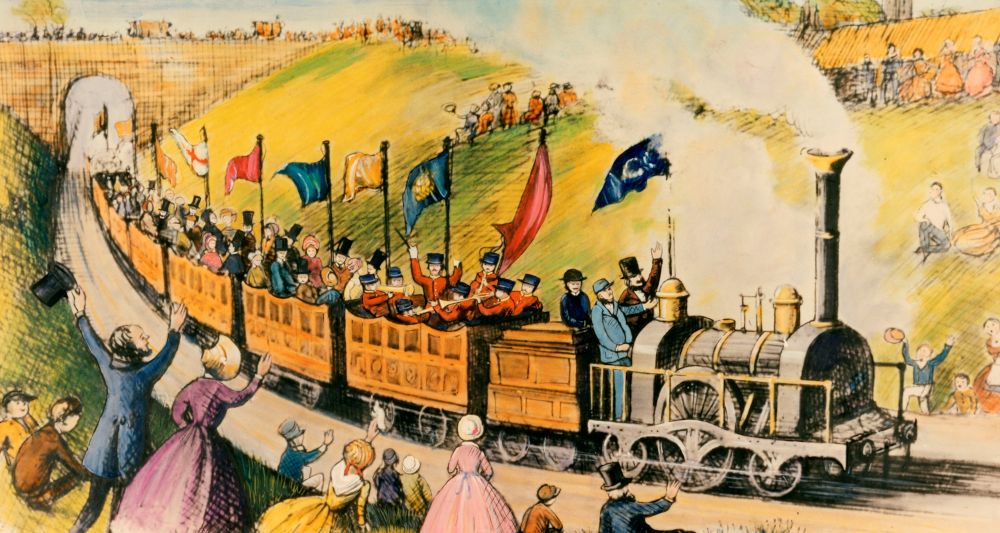

During the nineteenth century in Western Europe, the train was the symbol of technological progress. The first major railroad joined Brussels to Paris, a 200-mile trip that took twelve hours, a quarter of the time of that by stagecoach. Later, trains reach the speed of fifty miles per hour, causing many passengers to both marvel and take fright.[9]

Railways shrunk distances and compressed time. The hinterlands were brought closer to the urban centers. Poet Heinrich Heine, in 1845, called the train a “providential event,” comparable to the invention of gunpowder and the printing press “which swing mankind in a new direction, and changes the color and shape of life.” With respect to the new experience of space, he said, “I feel as if the mountains and forests of all countries are advancing on Paris. Even now, I can smell the German linden trees; the North Sea breakers are rolling against my door.”[10] All of Europe seemed to be in motion; the poet Baudelaire defined Modernity as “the transient, the fleeting, the contingent.”[11] Karl Marx analyzed how the “annihilation of space and time”[12] by railways and the telegraph globalized commerce.

People were on the move, too. The travel agency Thomas Cook and Son, in 1851, sold 165,000 return tickets on special excursion trains to the Great Exhibition in London. Cook, later, organized packages tours to Switzerland and Italy.

The world became much larger culturally. Trains reduced shipping costs that led to the growth of bookstores in provincial towns. Stations along the well-traveled rail lines had lending libraries and bookstalls. Travel on the rails fueled a boom in popular fiction, for many passengers desired entertaining literature to pass the time. Trains brought a provincial public to the museums, concert halls, and theaters in the cities and traveling artistic groups to the provinces.

In twentieth-century America, the automobile, not the train, became the symbol of freedom. The title of Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road captured the desire buried deep in every American heart — to be free, to throw off all social constraints. For many, the suburbs were an escape from the confines of a narrow ethnic community in an unglamorous part of the inner city. The automobile separated families and eventually killed the extended family in America.[13]

Automobiles, trains, and all mass technology rest upon a new means of material production — the division of labor. Instead of defining the division of labor, Adam Smith, the founder of modern economic theory, gives in his Wealth of Nations the example of the manufacture of pins. An unskilled workman could perhaps make twenty pins a day. With the advent of industrialism, the task of making a pin is broken into eighteen simple operations, with each workman skilled in performing one or two simple steps. Ten semi-skilled workers “could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day.”[14] If each worker completed all the tasks by himself, then the ten workers at best could make only two hundred pins. The division of labor increased production by 240-fold! No wonder Smith extols the division of labor as the greatest innovation in material production, ever.

Ford Assembly Line, Highland Park, Michigan Circa 1929.

Smith predicted that the vast number of material goods produced through the division of labor would require large markets, or in modern parlance a consumer society, where “a general plenty diffuses itself through all the different ranks of the society.”[15] No one can doubt that two hundred years of capitalism in America and Europe created for the wealthy and the poor a superabundance of goods.

To continue to exist, the capitalist economy must constantly produce new consumer goods, not unlike a shark that must keep swimming or die. Without the “great mass of inventions”[16] that flowed from science and technology, capitalism would have ground to a halt once markets were saturated by an abundance of goods. One obvious example is that without John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley, the inventors of the transistor, the iPhone would not exist, except for Dick Tracy.

New inventions and technologies continually produce new goods and thus previously unknown desires, and as a result, we are all placed on the treadmill of desiring more and more. The marketplace instills values: For “a general plenty”[17] to be consumed, an unlimited desire for material goods must be developed through advertising and mass media. In this way, everyone’s attention is focused on the good life in this world, away from salvation, at the expense of intellectual and spiritual values. Every increase in the wealth of a consumer society goes into more material goods and higher profits, not into the development of the worker-consumer as a human person.

In this essay, we suggest that historical change exhibits two general features. One we have already seen; the change from one historical era to another is a phase change like the melting of ice into water, each substance with its own properties, but unlike nature, the phase changes of history cannot be reversed. The other feature of historical change was enunciated by Sophocles 2,500 years ago: “Nothing that is vast enters into the life of mortals without a curse.”[18]

The dark side of capitalism is that the division of labor contracts the interior life of the worker. Surprisingly, Smith argues, again in The Wealth of Nations, that when a person performs one or two simple operations, as required by the division of labor, he “generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment.”[19] The interior life of an industrial worker collapses to what serves the machine. Smith maintains that industrialism produces an abundance of goods and a decline in the interior life of the worker. Alexis de Tocqueville agrees: “As the principle of division of labor is ever more completely applied, the workman becomes weaker, more limited, and more dependent. The craft improves, the craftsman slips back.”[20] In premodern economies, Smith notes, no one fell into the “drowsy stupidity” induced by the division of labor and “every man ha[d] a considerable degree of knowledge, ingenuity, and invention,” because the labor of the artisan developed the whole person.[21]

The division of labor is consonant with Descartes’ rule to begin with the smallest parts — recall the making of a pin was divided into eighteen separate, small operations. In a similar way, the Protestant Reformation divided a religious community into a collection of individual worshippers. Three principles defined the Protestant Reformation: the Bible as the sole authority, justification by faith alone, and the priesthood of all believers. All three served to substitute the individual for the community.

Instead of submitting to the Church’s explanations of the Bible, the Protestant turned to private interpretation. Instead of relying on the priesthood and the prayers of the saints and of other members of the Church, each Protestant struggled alone for his or her salvation, not through the intercession of the Saints, but by individual effort and personal faith in Christ the Savior. All believers were equally thought to be priests: “For whoever comes out of the water of baptism can boast that he is already a consecrated priest, bishop, and pope,” Martin Luther taught.[22] In effect, each Protestant became his or her own church. “The quintessentially modern idea of the individual — and of one’s personal responsibility before one’s self and God rather than before any institution, whether church or state — was as unthinkable before Luther as is color in a world of black and white,” writes Eric Metaxas in his biography of Luther.[23]

“Out of this atomization of religious corporatism emerge[d] the new man of God, intent upon salvation through unassisted faith and unmediated personal effort,” sociologist Robert Nisbet concludes from his study of the modern quest for community.[24] In America, the Puritans put an indelible stamp of individualism upon the New World. After a livelong study of Puritanism, historian Perry Miller writes, “The Protestant sense of the individual, of the single entity which is one entire person, who must do everything of himself, who is not to be cosseted or carried through life, who in the final analysis has no other responsibility but his own welfare, this ruthless individualism was indelibly stamped upon the tradition of New England . . . . Both in economics and in salvation, the individual had to do everything of himself.”[25]

In America, individualism was not an idea found in philosophical treatises, but a lived experience. Tocqueville, while traveling through the dense woods in Michigan, in 1831, came across a pioneer and his family, making the “first step toward civilization in the wilds.”[26] He noted in his travel diary that “from time to time along the road, one comes to new clearings. As all these settlements are exactly like one another, whether they are in the depths of Michigan or just close to New York, I will try and describe them here once and for all.”[27] The settler’s log house showed “every sign of recent and hasty work.” The walls and roof were fashioned from rough tree trunks; moss and earth had been rammed between the logs to keep out cold and rain from inside the house. The settler exhibited little curiosity in his French visitor, and in showing hospitality to the stranger, he “seemed to be submitting to a tiresome necessity of his lot and in it saw a duty imposed by his position, and not a pleasure.” The pioneer and his family formed a “little world” of their own, an “ark of civilization lost in a sea of leaves. A hundred paces away the everlasting forest spread its shade, and solitude began again.”

The pioneer, living in an “ark of civilization lost in a sea of leaves,” had left behind in Old Europe parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins, everyone to impede his freedom and independence.

Tocqueville captured in one word the essence of Modernity. He was the first person to use the word “individualism” and reports “that word ‘individualism,’ which we coined for our own requirements, was unknown to our ancestors, for the good reason that in their days every individual necessarily belonged to a group and no one could regard himself as an isolated unit.”[28] The Latin word “indīviduum,” the root of the English word “individual,” means an indivisible whole existing as a separate entity.

Stated in its most general form, the defining principle of Modernity is that every whole — a political community, a horse, or a carbon atom — is a sum of its isolated parts. We call this principle individualism, a straightforward extension of Tocqueville’s original meaning and of Descartes’ rule to begin with the parts. Modernity rests upon three legs: science and technology, democracy, and capitalism; all three legs are bound together by individualism. The overarching principle of Modernity, then, is that things exist in isolation as separate entities.

But human beings are social by nature and cannot live as separate entities in isolation. In the Nation-State, individuals are bound together by nationalism. Patriotism, the love of place, countrymen, and local traditions, lasted for millennia until replaced by nationalism, which first appeared in seventeenth-century England. Nationalism is so prevalent in Modernity that we believe it is a natural outgrowth of tribal life, instead of an invention of Western Europe exported to the rest of the world. According to historian Hans Kohn, nationalism has three essential aspects: “Under Puritan influence the three main ideas of Hebrew nationalism were revived: the Chosen People, the Covenant, and the Messianic expectancy. The English nation regarded itself as the new Israel.”[29]

The Catastrophes of Modernity

Every Nation-State instills nationalism into the minds of its citizens. Consider Leonard Thompson, born in 1896 to a family of farmworkers in County Suffolk, England. Leonard described his parents as “very religious and very patriotic.”[30] The entire family of ten loved to sing. To them, “the patriotic songs and the church hymns seemed equally holy; they took away our breath,” and blurred the difference between God and England.

Leonard began to work on surrounding farms when he was eight; later to escape being “worked to death,” he joined the army in 1914 and became a machine gunner in the Third Essex Regiment. Soon, he was engaged in trench warfare against the Turks. In Suffolk, he had never seen a dead man, and now he was burying hundreds in the English trenches, whose bottoms were “springy like a mattress because of all the bodies underneath.” Yet, “we didn’t feel indignant against the Government. We believed all they said, all the propaganda.” Years later, Leonard thought differently: “We were all so patriotic then and had been taught to love England in a fierce way.”

In the twentieth century, Nation-States, large and small, waged war among themselves, some against their own citizens. The power of the New Gods, enhanced by modern science and technology, produced a century of political murder. A partial, conservative catalog of the horrors is mind-boggling, unbelievable, but undeniable. Deaths: World War I (military only): 9,700,000; Spanish Civil War: 1,200,000; World War II (military and civilian): 51,000,000; Japanese Rape of Nanking: 300,000 Chinese; Allied bombing of Hamburg, Berlin, Cologne, and Dresden: 500,000 German civilians; Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 210,000 Japanese civilians; Vietnam War (military and civilian): 5,000,000.[31]

Two other catastrophes of Modernity are the Gulag and the Holocaust. In Bacon’s vision of the new science, experiment would give mankind the power to command nature that Adam had in the Garden of Eden. In the new Paradise on Earth, the command of nature would contribute to the “relief of man’s estate,”[32] a way to treat some diseases, bring about modest improvements of health, and perhaps increase physical comfort and pleasure — “in some degree [to] subdue and overcome the necessities and miseries of humanity.”[33]

In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels gave a vision of the future Paradise on Earth that outstripped Bacon’s: “When, in the course of development, class distinctions have disappeared, and all production has been concentrated in the hands of a vast association of the whole nation, the public power will lose its political character. Political power, properly so-called, is merely the organized power of one class for oppressing another.” In the grand vision of the Manifesto, history ends with the disappearance of oppressors and the arrival of freedom for all: “In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.”[34]

Instead of Paradise, the social experiment in the Soviet Union to establish the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth produced Hell on Earth with the deaths of over 15,000,000 people; later, Chairman Mao with the Great Leap Forward would top the Soviets with the political murder of 30,000,000 people. Maybe, Pol Pot should win the Gold Medal for Utopianism. He and his Khmer Rouge restarted civilization in the Year Zero, the time when revolutionary ideals replaced all culture and traditions within a society. Slave labor, malnutrition, poor medical care, and executions killed a quarter of the population of Cambodia.[35]

Hitler, Himmler, and Eichmann took Messianic nationalism to its logical conclusion. To demonstrate that the Aryans are the Chosen People, they murdered six million Jews and disposed of their bodies in mass crematoria. The Nazi theologians argued, “How could the Jews be the Chosen People, when we use their ashes for tire traction on ice? Therefore, we are the Chosen People. Q.E.D.” Primo Levi, a survivor of Auschwitz, locates the foundation of Nazi doctrine as anti-Semitism. For the Nazis, he writes, “the Jews could not be ‘the people elected by God,’ since that’s what the Germans were.”[36]

The Holocaust annihilated Nietzsche’s myth that the ascendance of the Overman, the perfect race, will raise humankind to a new level of existence; the Gulag destroyed the utopian story of humans instituting a perfect political order; Hiroshima killed the comforting narrative that the progress of science and technology lead to universal happiness. We live in the wreckage of Modernity that calls into doubt the Nation-State, progress, and science.

Postmodernity

Undivided Wholeness

Once again, human history is undergoing a phase change caused by a new science and technology. Stated succinctly, the fundamental principle of Modernity, things exist in isolation, as separate entities, is being replaced by undivided wholeness of quantum physics. The experimenter and the observing instrument in quantum physics are not separate from what is observed.[37] The knower and the known form an indivisible whole; to speak of the universe in the absence of any knower is absurd. Niels Bohr, the guiding light of the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum physics, states the new understanding of the scientist, “In the great drama of existence, we ourselves are both actors and spectators.”[38] The isolated, autonomous individual is a cultural lie.

The early stages of historical phase changes are always confusing, difficult to discern clearly, and resisted by many; consequently, the current phase change is easiest to see in the new technology, just as the previous phase change became immediately apparent to poets who grasped how trains were transforming economic and social life.

The Whole World

The transistor, the personal computer, and the cell phone were made possible because of the deep understanding of matter provided by quantum physics. The Apple II went on sale in June 1977 and the IBM PC in August 1981. Tim Berners-Lee, while a fellow at CERN in 1989, invented the World Wide Web. The mouse and the Graphical User Interface made the Internet available for the technically ignorant; Netscape, the first browser, was released on December 14, 1994. The first smartphone, iPhone 1, was released on June 29, 2007. According to Statista, there are 3.3 billion smartphone users in the world today. Seventy-nine percent of Americans use a smartphone.[39] Go into any coffee shop, college dining hall, or airport lounge, and it seems like everyone is on a smartphone, texting a friend, reading email, surfing the Web, or watching a movie.

The ubiquity of digital devices makes the number of people who share the same experience staggering. Take YouTube. The views of Leonard Cohen: Hallelujah (Live in London) is 147 thousand, of Justin Bieber: Sorry 3.2 billion, and of the children’s cartoon Masha and The Bear: Recipe for Disaster, originally in Russian, 4.2 billion. The comparison number here is the human population of the Earth, 7.7 billion.

Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris catches fire and local videos of the catastrophic blaze are immediately on social networks. A volcano erupts on White Island, New Zealand, killing seventeen tourists, and within hours, videos of other tourists being rescued and of the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Ardern, giving an update of the tragic event are seen in Peoria, Illinois.

The previous cultural shift from the provincial to the urban has been expanded to the entire world by digital technology, and that shift has political consequences.

Our Choices Affect the Whole World

In 2015, Christine Figgener, a marine biologist, found a male olive ridley sea turtle during a research trip to Costa Rica. The turtle had a four-inch plastic straw lodged in its nostril. Dr. Figgener videographed herself using a pair of pliers to remove the straw that caused great pain and substantial bleeding to the turtle. Most of us have not lived on a farm and seen chickens or sheep slaughtered for our dinner, so we cringe when we see a poor turtle in pain and bleeding, even though it is being rescued.

Dr. Figgener’s YouTube video went viral with over 38 million views and gave the movement to ban plastic straws a tremendous boost. In Postmodernity, the political consequences of viral videos can develop rapidly. July 2018, Seattle became the largest U.S. city to ban plastic straws. January 2019, California became the first state to ban plastic straws at full-service restaurants. By December 2020, Starbucks plans to ban plastic straws from all its stores.

Sea Turtle with Straw Up Its Nostril.

In the previous era of Baconian science, in the Mechanical Age, the efficiency of production, the convenience to the consumer, and the creative destruction of capitalism were the principal “moral” values. In the Digital Age, the nearly universal moral question is, “How does our behavior affect other persons, animals, and the environment?” This is not a question just asked by bleeding-heart liberals.

Tucker Carlson on his weekday program on Fox News featured a story about Paul Singer, a hedge fund manager and the second largest contributor to the Republican Party in 2016. Elliot Management, Singer’s hedge fund, bought eleven percent of Cabela’s, a large retailer that sells fishing and hunting gear. To make a quick profit on his investment, Singer forced the management of Cabela’s to sell to Bass Pro Shops, even though Cabela’s turned a profit on its $4 billion of total revenue the previous year. The new owner moved the headquarters of Cabela’s with its 2,000 good-paying jobs from Sydney, Nebraska, population 6,282. Sydney was destroyed, but Paul Singer made at least $93 million.

Tucker Carlson could not hide the moral outrage in his voice when he said the model for the destruction of America is “ruthless economic efficiency. Buy this distressed company, outsource the jobs, liquidate the valuable assets, fire middle management, and once the smoke is cleared, dump what remains to the highest bidder, often in Asia.” (See Hedge fund forced Cabela’s merger, decimated jobs in Sidney, Nebraska.)

The Sophoclean Curse

The connection to the whole world destroyed the myth of a Chosen People, and consequently, the Nation-State lost its divine aura. The old guard continues to pursue securing economic and political spheres of dominance; the abandonment of military conscription allows the American government to engage in military operations in Africa, Afghanistan, and the Middle East with citizens at home taking little notice. But the lives of few young Americans are dominated by the patriotic stories told by their flag-waving great-grandparents. For the youth of the Digital Age, the new reality that is replacing the Nation-State worldwide is the Big Five — Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, and Alphabet, the parent company of Google.

Social media, not nationalism, is becoming the new glue that holds Americans together: 27 percent of adult Americans use Snapchat, 35 percent Instagram, 68 percent Facebook, and 73 percent YouTube.[40] Social media is causing society to fragment into small, digitally connected groups. The median number of friends a Facebook user has is roughly 150.[41] But these small groups are not like those of small New England villages in the 1800s, where Yankees lived together daily and could not avoid face-to-face contact. The Internet has greatly expanded the world and, at the same time, weakened human relationships.

A farmer plowing his field in the Merrimack Valley of New Hampshire had memories of family, neighbors, and people he passed on the road going to and from the market and knew the names of characters in the Bible and outstanding patriots, such as Washington and Jefferson. At school, he had learned stories, ballads, and episodes of American history that taught a moral lesson. With the advent of the image-world of movies, television, and the Internet, everything changed. Movie critic Geoffrey O’Brien declares that in the new image-culture “half the faces in the memory bank [of a person] are of public personalities, actors playing fictional characters.”[42]

According to a 2016 Nielsen report, the total amount of time American adults spend on average in the Image-World, namely watching TV, surfing the Web on a computer, and using an app/Web on a smartphone, is eight hours and forty-seven minutes per day.[43] As a result, Americans acquire the habit of judging people and products by feelings; likes and dislikes determine whether a song, a movie, a sitcom, a celebrity, or a political candidate is up or down. In the Image-World, reasoned argument is replaced by emotional judgment.

Technology administered the coup de grâce to truth. The Internet is the first medium in history, besides the agora of ancient Athens and the town meetings in New England villages, to create many-to-many communication; the phone is one-to-one, and books, radio, and television are one-to-many. Clay Shirky, a prominent thinker on the social and economic effects of the Internet, points out that “every time a new consumer joins this media landscape a new producer joins as well, because the same equipment — phones, computers — let you consume and produce. It’s as if, when you bought a book, they threw in the printing press for free.”[44]

Social media allow hundreds of millions of Americans with the click of a mouse to disseminate their opinions without the scrutiny of grammarians, fact-checkers, and editors, the guardians of print culture. Anyone, anywhere, anytime, now, can instantly post an opinion on anything. The Internet has become an ocean of democratic opinion, one comment washing over another, quickly submerging whatever truth that tries to surface.

Expert assessment based upon objective, rational analysis reeks of elitism. Scientific data and peer-reviewed reports on climate change are posted on the Internet, but videos of fires in New South Wales, Australia and photographs of thawing permafrost and sinking tundra in Newtok, Alaska move people to protest and sign petitions against fossil fuel corporations.

What Is Next?

History is not a predictive science like Newtonian physics; human beings have free will that allows them to behave imaginatively for good or bad; the tragedy is that they are often blind to the consequences of their actions. Trying to read the tea leaves of Post-Modernity, we are limited to pointing out possibilities, knowing that we may miss what turns out to be the most important emerging pattern that is obvious fifty years from now.

Artificial Intelligence

Deep learning is at the core of artificial intelligence (AI). Computers programmed with deep learning take a huge amount of data within a single domain and learn to predict or decide at superhuman speed and accuracy. Many jobs are mechanical in the sense that the same operation is performed again and again. Consider the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy, a condition where the nerves and blood vessels in the retina are damaged by complications of diabetes. Computers were trained to search for patterns in photographic images of the retinas of diabetics and non-diabetics. After several months of training, computers achieved a 95 percent accuracy in diagnosing diabetic retinopathy, an accuracy at or above the average ophthalmologist, who required thirty years of schooling and specialized training.[45]

Many jobs that we do not think of as mechanical can be replaced by AI computers. The self-driving car is already almost four times safer than a human-operated car: one crash every 1.92 million miles versus one crash every 492,000 miles.[46]

In a world where computers outperform us in analyzing data, carrying out mechanical operations, and increasing efficiency, we are left with what differentiates us from computers — magination, insight, and compassion. A computer is indifferent to whether a patient is diagnosed with two months to live or is disease-free. A doctor or a nurse can hold the patient’s hand; a priest or psychotherapist can help the patient confront his mortality. Modern society desperately needs caregivers for the ill and elderly, teachers for children, guides for young adults, and love for the neglected, abandoned, and forgotten.

AI can liberate us from repetitive labor that Smith said renders the worker “not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment.”[47] The industrialism that required that humans perform like machines — a demand that did violence to the soul as well as the body — is destined to end. Machines, then, will do the work of machines, somewhat like the original Garden of Eden, where supposedly “the agricultural implements worked for him [Adam] of themselves, like automata.”[48]

Be More, Not Have More

Before the full realization of Modernity, Tocqueville wrote, “In America, I have seen the freest and best educated of men in circumstances the happiest to be found in the world; yet it seemed to me that a cloud habitually hung on their brow, and they seemed serious and almost sad even in their pleasures,” because they “never stop thinking of the good things they have not got.”[49]

Material prosperity in America did not bring about general happiness; from 1940–1995, as material prosperity increased, people reported a decrease in happiness, according to the Statistical Abstract of the United States.[50] The illustration shows that for more than fifty-some years personal income has increased substantially, but the percentage of people who report they are very happy has not budged.[51]

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman and economist Angus Deaton analyzed the responses of more than 450,000 United States residents surveyed in 2008 and 2009 about their emotional well-being. Kahneman and Deaton focused on an “individual’s everyday experience — the frequency and intensity of experiences of joy, stress, sadness, anger, and affection that make one’s life pleasant or unpleasant.” They sought an answer to the question, “Does money buy happiness?” Not surprisingly, “low income exacerbates the emotional pain associated with such misfortunes as divorce, ill health, and being alone.” Unexpectedly, Kahneman and Deaton discovered that emotional well-being does not increase significantly beyond an annual household income of $75,000. “More money does not necessarily buy more happiness.”[52]

For nearly two centuries, Americans have been acquiring more and more, believing material prosperity equals happiness. Go into Walmart, Costco, Bergdorf Goodman, Nordstrom, or Neiman Marcus, an amazing abundance of goods, and so little happiness. Perhaps, just perhaps, truth has burnt up error, and we have learned that we are spiritual, not material beings. The goal of material production, then, is to help realize the aspiration to be more, not the craving to have more.

A New World

We are in desperate need of a vision that life can be good.

In the new world struggling to be born, the madness of acquiring more and more is absent. Inhabitants desire to be more, to connect with others through love and friendship, to develop the interior life through poetry and music, to seek wisdom through philosophy and theology, and to fully embrace that they are spiritual beings and forcefully reject that they are collections of quarks and leptons, mere meat machines driven by pain and pleasure. Wide recognition of our true nature has enormous political and economic consequences.

Consider the current solution to climate change: windmills and solar farms to eliminate fossil fuels and thus reduce CO2 emissions, while continuing unabated our mad acquisition of more and more. The obvious solution to climate is to change our way of living, so we consume far less. But most of us are like alcoholics; we know our addiction is bad for us, will never give us lasting happiness, and only introduces new problems in our lives; yet, we cannot stop our destructive behavior. The new iPhone, the cruise to Hawaii, and the new Prius are drug hits that quickly fade.

A widespread desire to be more leads to an economy where natural resource use is stabilized within ecological limits and where the goal of an increasing GDP is superseded by the goal of the physical, social, and spiritual well-being of everyone. The enormous wealth generated by technology can support poets, artists, and musicians as well as professional athletes, hedge fund managers, and vulture capitalists. The inevitable loss of repetitive labor can lead to architects, engineers, and construction workers rebuilding the postindustrial landscape, where strip malls and urban expressways are a visual nightmare of the past.

The threat of a war that destroys humanity through the insane use of nuclear weapons is always present; however, the weakening of the Nation-State does lead to an average citizen uninterested in a National Empire and the division of the world into economic and political spheres of dominance.

The above vision is not utopian; evil, suffering, class structure, and the rich and the poor will always be with us. The twentieth century, the century of mass political murder, demonstrated that any attempt to establish Paradise on Earth ends in disaster; however, we can strive for a better society that aims to establish the well-being of all and a culture that embodies truth, beauty, and justice.

Illustrations courtesy of Wikimedia.

“Trouble in Paradise” is for Peter V. Sampo in memoriam.

Endnotes

[1] Francis Bacon, The New Organon and Related Writings (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1960 [1620]), p. 22.

[2]Ibid., p. 19.

[3] Ibid., p. 29.

[4]René Descartes, Discourse on Method in The Philosophical Works of Descartes, trans. Elizabeth S. Haldane and G.R.T. Ross (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), Vol. I, Part V, p. 139.

[5]Ibid., Vol. I, Part I, p. 92.

[6] H. Allen Orr, “Awaiting a New Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, 60, No. 2 (February 7, 2013).

[7]Bacon, The New Organon, p. 103.

[8] For a timeline of inventions, see http://theinventors.org/library/inventors/bl1700s.htm.

[9] The data on train travel in nineteenth-century Europe is from Orlando Figes, The Europeans: Three Lives and the Making of a Cosmopolitan Culture (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2019).

[10] Heinrich Heine, quoted by Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014), p. 37.

[11] Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, trans. and ed. John Mayne (New York: Phaidon, 1965), p. 13.

[12] Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, written 1857–61, published: in German 1939–41, trans. Martin Nicolaus, p. 449, available https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/index.htm.

[13] See Barry Levinson’s film Avalon for a brilliant rendering of how the automobile killed the extended family in America.

[14] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations [1776]), Bk. I, Ch. I. Available http://www.econlib.org/library/Smith/smWN.html.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Bacon, The New Organon, p. 103.

[17] Smith, Bk. I, Ch. I.

[18] Sophocles, Antigone, trans. R. C. Jebb, line 614, http://classics.mit.edu/Sophocles/antigone.html.

[19] Smith, Bk. V, Ch. I.

[20] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Harper & Row, 1966 [1835, 1840]), p. 556.

[21] Smith, Bk. V, Ch. I.

[22] Martin Luther, “Open Letter to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation,” in Martin Luther, Three Treatises, trans. Charles M. Jacobs (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1960), p. 14.

[23] Eric Metaxas, Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World (New York: Viking, 2017), p. 1.

[24] Robert Nisbet, The Quest for Community (New York: Oxford University Press, 1953), p. 90.

[25] Perry Miller, “Individualism and the New England Tradition,” in The Responsibility of Mind in a Civilization of Machines: Essays by Perry Miller, ed. John Crowell and Stanford J. Searl, Jr. (Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1979.), pp. 5, 6.

[26] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Appendix U, pp. 731-733. For narrative consistency, several verb tenses in the text have been changed to the past.

[27] Alexis de Tocqueville, Journey to America, ed. J. P. Mayer, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Anchor: 1971), p. 360.

[28] Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Régime and the French Revolution, trans. Stuart Gilbert (New York: Doubleday, 1955 [1856]), p. 96.

[29] Hans Kohn, Nationalism: Its Meaning and History (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1965), p. 16.

[30] Leonard Thompson’s narrative is in Ronald Blythe, Akenfield: Portrait of an English Village (New York: New York Review of Books, 2015 [1969]), pp. 33-49.

[31] For a discussion of genocide in the century of mass murder, see Lewis M. Simons, “Genocide and the Science of Proof,” National Geographic Magazine (January 2006): 28-35 and Timothy Snyder, “Holocaust: The Ignored Reality,” The New York Review of Books (July 16, 2009).

[32] Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning, ed. William Aldis Wright (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963 [1605]), p. 43.

[33] Bacon, The New Organon, p. 23.

[34] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm.

[35] See Endnote 30. 100,000 Cambodians peasants were killed in the 1972-1973 bombing campaign initiated by President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. The number of bombs dropped on Cambodia was over three times that dropped on Japan in World War II. So, much for technological progress.

[36] Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved, trans. Raymond Rosenthal (New York: Vintage, 1989), p. 179.

[37] Renegade physicist David Bohm, in Wholeness and the Implicate Order (London: Routledge, 1980), introduced “undivided wholeness,” which we developed in our own, specific way to indicate that the experimenter, the observing instrument, and the observed cannot be separated. See George Stanciu, “Quantum Physics and Mind,” (August 2019), https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2019/08/quantum-physics-mind-george-stanciu.html.

[38] Neils Henrik Bohr, Essays 1958-1962 on Atomic Physics and Human Knowledge (New York: Wiley, 1963), p. 15.

[39] “Top 25 Countries/Markets by Smartphone Users,” https://newzoo.com/insights/rankings/top-countries-by-smartphone-penetration-and-users/.

[40] John Gramlich, “5 facts about Americans and Facebook,” http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/10/5-facts-about-americans-and-facebook/.

[41] Aaron Smith, “What people like and dislike about Facebook,” http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/02/03/what-people-like-dislike-about-facebook/.

[42] Geoffrey O’Brien, The Phantom Empire: Movies in the Mind of the 20th Century (New York: Norton, 1993), p. 218.

[43] The Nielson Total Audience Report, Q1, 2016. Available file:///C:/Users/George/OneDrive/Word%20New/Submissions%202016/Documents/total-audience-report-q1-2016.pdf.

[44] Clay Shirky, “How Social Media Can Make History,” Ted Talk, 2009, https://www.ted.com/talks/clay_shirky_how_cellphones_twitter_facebook_can_make_history.

[45] Andy Chan, “Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work,” https://www.ted.com/talks/andy_chan_artificial_intelligence_and_the_future_of_work

[46] Ibid.

[47] Smith, Bk. V, Ch. I.

[48] Mircea Eliade, Myths, Dreams, and Mysteries, trans. Philip Mairet (New York: Harper, 1960), p. 43.

[49] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 536.

[50] See Robert E. Lane, The Loss of Happiness in Market Democracies (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 2001), p. 5.

[51] The graph Happiness and Income in the United States is courtesy ofwww.davidmyers.org.

[52] Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, “High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (August 4, 2010) 107 (38): 16489–16493. Available http://www.pnas.org/content/107/38/16489.full.