|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

The Covid-19 Pandemic has revealed that we no longer have the equivalent of such moral leaders as Martin Luther King, Jr., Caesar Chavez, and Dorothy Day. These leaders in their actions embodied the Gospel of Love and the unshakeable Christian understanding of the human being taken from the Book of Genesis: “God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.”[1]

Every Christian denomination holds that in some way God, or Christ, is in each person and consequently possesses a dignity that must be respected. Created in the image of God, no person is a thing; each person is a rational being with the freedom to choose to act or not to act. Economic, social, political, and cultural conditions often violate the dignity of certain persons or encourage others to exercise their freedom unjustly.

That many of the powerful do not acknowledge the image of God in the weak has become apparent during the Covid-19 Pandemic. The millions of essential workers paid subsistence wages are no longer hidden from white, middle-class Christians.

Consider that the abundant, affordable food in America results from advanced technology and workers treated as things. Production workers at a Tyson meat processing plant in Arkansas earn on average $12.65 an hour to process 140 chickens per minute. Team members, the majority of them immigrants, refugees, African-Americans, and Hispanics, stand shoulder to shoulder cutting and deboning birds that fly by so quickly that a worker cannot pause to cover a cough and thus may be exposing others to the Covid-19 disease; with no regularly scheduled bathroom breaks, some workers wear diapers.[2] As of June 19, 2020, 3,748 team members were tested onsite for the Covid-19 virus, 13% were positive.[3]

John Tyson, the chairman of the board of Tyson Foods, is a good Presbyterian and confessed, “I felt my calling and my responsibility was to create an environment of permission for people to live their faith — whatever that faith may be.”[4] Today, Tyson Foods employs one hundred Chaplains from various Christian denominations; Lutheran, Catholic, Pentecostal, Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist are all represented. The Chaplains counsel the stressed, the despondent, and the grieving, assist immigrants with English, celebrate marriages and births, and pray at the groundbreaking of new buildings.

Karen Diefendorf, an ordained pastor and the Director of Chaplain Service for Tyson Foods, explained, “One of the core values of Tyson Foods is we strive to be faith-friendly and inclusive. It does not matter what your belief system is, whether it is religious or philosophical, for that matter. When you come to this place, your beliefs are welcome.”[5]

A pastor at Tyson Foods comforting a woman whose mother just died of a stroke is a wonderful example of the second great commandment that Jesus gave us: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”[6] However, for a pastor to remain silent after witnessing that the line workers are commodities, things to be used for the creation of wealth is appalling, for Jesus also preached, “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me.”[7]

Property as understood by capitalism and Christianity

When a pastor ignores the defilement of the image of God in a production worker processing 140 chickens a minute, earning $12.65 an hour, and wearing diapers because of the lack of scheduled bathroom breaks, he or she most likely adheres, perhaps unwittingly, to the preaching of the two great apostles of American capitalism, Milton Friedman and Ayn Rand. Friedman taught that “in all systems, whether you call them socialism, capitalism, or anything else, people act from self-interest. The citizens of Russia act from self-interest in the same way that the citizens of the United States do.”[8] Rand, a staunch advocate of individualism, claimed in her book The Virtue of Selfishness, that an individual who pursues another’s good “has nothing to gain from it, he can only lose; self-inflicted loss, self-inflicted pain and the gray, debilitating pall of an incomprehensible duty is all that he can expect. He may hope that others might occasionally sacrifice themselves for his benefit, as he grudgingly sacrifices himself for theirs, but he knows that the relationship will bring mutual resentment, not pleasure.”[9]

According to the ethos of capitalism, no one acts for the sake of another, since self-interest governs all human relations. An individual can at best offer an exchange to another motivated by self-interest, expecting some kind of return, such as devotion, power, money, or pleasure. Underlying this ethic is the opinion that an individual barely holds on to life, needing food, shelter, clothing, and other easily lost goods. An individual hopes to take much and give little in return; his or her existence is beggarly.

In contrast, Alexis de Tocqueville, in Democracy in America, warned Americans that if they were “to remain ignorant and coarse [in their single-minded pursuit of wealth], it would be difficult to foresee any limit to the stupid excesses into which their selfishness might lead them, and no one could foretell into what shameful troubles they might plunge themselves for fear of sacrificing some of their own well-being for the prosperity of their fellow men.”[10]

All of us, not just the pastors at Tyson Foods, are imbued with a capitalistic understanding of property, the opposite of the Christian understanding. John Tyson is worth $2 billion. Most of us believe that his success was entirely due to him, and no one, not even the wretched and the poor, has a legitimate claim on his property. St. Thomas Aquinas teaches otherwise. For St. Thomas and in principle for every Christian, the earth and all its plants and animals belong to the Creator and thus “each one is entrusted with the stewardship of his own things, so that out of them he may come to the aid of those who are in need.” And the Doctor of the Church adds, “whatever certain people have in superabundance is due, by natural law, to the purpose of succoring the poor. For this reason, Ambrose and his words are embodied in the Decretals: ‘It is the hungry man’s bread that you withhold, the naked man’s cloak that you store away, the money that you bury in the earth is the price of the poor man’s ransom and freedom.’”[11]

We modern-day readers of the Summa Theologica do not deny John Tyson the right to continue to use his wealth to collect paintings by Willem de Kooning, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol, or even to buy a yacht or an island in the Caribbean if he so desires; we will even ignore St. Thomas’ valid argument that superabundance is stealing from the poor. The modest Christian request is that Tyson Foods’ profit of $3.055 billion in the fiscal year 2018, which is $25,041 per worker, should have been shared with team members in higher wages, a profit-sharing plan, or a yearly bonus.

The economic decline of the low-wage worker

A low-wage workforce is not unique to Tyson Foods. Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman, both of the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program, calculated that “more than 53 million people — 44 percent of all workers aged 18-64 — are low-wage workers. They earn median hourly wages of $10.22 and median annual earnings of $17,950.”[12] Ross and Bateman attribute low wages to the near elimination of private sector unions, to automation and the offshoring of manufacturing jobs, and to tax policies that favor corporations and the rich.

Harvard economists Anna Stansbury and Lawrence H. Summers observe that for low-wage earners “the American economy has become more ruthless, as declining unionization, increasingly demanding and empowered shareholders, decreasing real minimum wages, reduced worker protections, and the increases in outsourcing domestically and abroad have disempowered workers.”[13] Many low-wage earners say it is better to have a [expletive] job than no job at all.

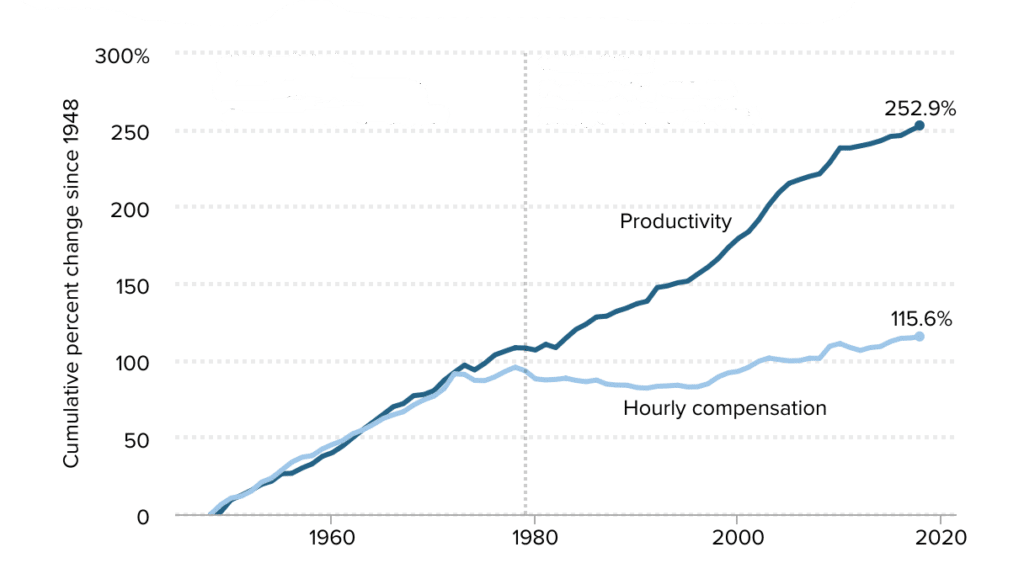

In 1973, productivity and worker income became uncoupled. (See Graph 1.) After adjusting for inflation, today’s average hourly wage has roughly the same purchasing power it did in 1978. In real terms, average hourly earnings peaked more than 45 years ago: The $4.03-an-hour rate recorded in January 1973 had the same purchasing power that $23.68 would today.[14]

Daron Acemoglu, an economist at M.I.T., cautioned that “raising the minimum wage and protecting these workers by safety regulations and by increasing their bargaining power would help some but is not a comprehensive solution. In today’s technological environment and business environment, if you raise the minimum wage, firms will go more in the direction of automating those jobs. Low-wage workers will be the losers.”[15] Like most economists, Acemoglu sees the low-wage workforce as a technical problem, not the result of moral failing; the free market by consensus is not subject to moral constraints and does not institutionalize greed. But Acemoglu does worry that “low-wage workers are doing really badly, and this will destroy our society.”[16]

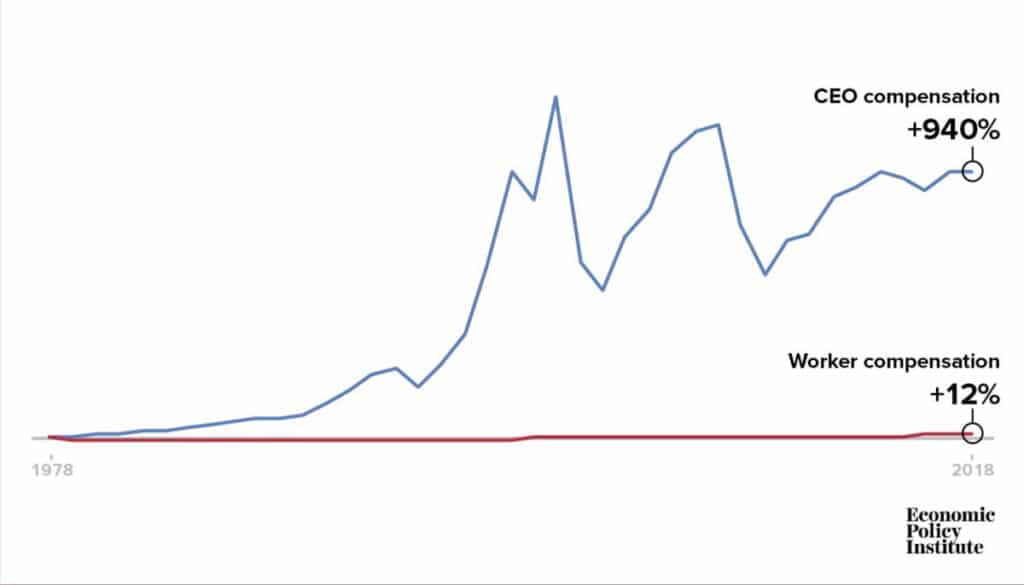

Over the forty years from 1978-2018, worker compensation increased by 18%, while CEOs’ compensation increased by 940%. (See Graph 2.) In 2007, 300,000 Americans collectively enjoyed almost as much income as the bottom 150 million Americans. The upper 1% took in 23% of the nation’s income. In 2017, the top 1% controlled 38.6% of America’s wealth. Twenty billionaires were worth as much as the bottom half of America. The five heirs to the Walmart fortune were worth $140 billion.

We are in need of another Gospel lesson. The Pharisees and the Herodians, representatives of the religious and the political elites, asked Jesus a trick question: “Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not? Should we pay them, or should we not?” The question was skillfully posed. If Jesus were to answer that we should pay taxes to the emperor, he would discredit himself with his followers, many of whom resented the unjust imperial rule. If he were to say no, people should no pay taxes to the emperor, he could be charged with sedition, a capital offense.

“He said to them, ‘Why put me to a test. Bring me a coin. [The coin was a denarius, a Roman coin that had an image of the emperor with the inscription, “son of God.”] He said to them, ‘Whose likeness and inscription is this?’ They answered, ‘Caesar’s.’ Jesus said to them, ‘Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s.’”[17]

The followers of Jesus knew that the ten commandments forbid the making of a graven image, that Caesar’s claim to be the son of God was blasphemous, and that Psalm 24.1 proclaimed, “The earth belongs to the Lord. And so does everything in it.”[18] Nothing belongs to Caesar.

I suspect that today most priests and pastors draw the opposite conclusion: The physical world belongs to Caesar and the spiritual realm to God. But history and current experience show that the Caesars of the world claim everything and leave nothing to God. The twenty-six richest billionaires own as many assets as the 3.8 billion people who make up the poorest half of the planet’s population.[19] Recall that Aquinas taught that the goods of the earth are entrusted in stewardship to aid those in need. If superabundance does not aid the poor, then such wealth is theft.

The two ethos of America: “Success Is Everything” and “Love One Another”

I wish to suggest that all of us, religious and laypersons alike, heard in Sunday school and repeatedly in sermons and homilies that God is Love and that we should love others as Jesus loved us, yet the ethos we came to live was taught and practiced first in elementary school and continued through graduate school. Public and parochial schools are founded on grading, a system of competition that instills the ethos of capitalism.

The most lasting lessons in competition are given in the classroom, not in the workplace or on the playing field. Anthropologist Jules Henry describes how competition entered into a fifth-grade arithmetic lesson he observed: “Boris had trouble reducing 12/16 to the lowest terms, and could only get as far as 6/8. The teacher asked him quietly if that was as far as he could reduce it. She suggested he ‘think.’” Undoubtedly, Boris remembered hearing the teacher tell him to reduce the fraction to lowest terms, but then he could not speak. When the teacher told him to think, his mind was probably paralyzed, and his ears buzzed. Other children, frantic to correct Boris, waved their hands to get the teacher’s attention. The teacher, quiet and patient, ignored the waving hands, and asked Boris, “Is there a bigger number than two you can divide into the two parts of the fraction?” After a long silence from Boris, she asked the same question again, this time more urgently, and still there was not a word from Boris. She then turned to the class and said, “Who can tell Boris what the number is?” A forest of hands appeared, and the teacher called on Peggy, thrilled to give the correct answer, four. Both Peggy and Boris see the classroom as a place where they are told to do certain things and praised if they do them right, disapproved if they do not.

Henry comments on the grade-school lesson in competition he witnessed: “Boris’ failure has made it possible for Peggy to succeed; his depression is the price of her exhilaration; his misery the occasion for her rejoicing. This is the standard condition of the American elementary school, and is why so many of us feel a contraction of the heart even if someone we never knew succeeds at garnering plankton in the Thames: Because so often somebody’s success has been bought at the cost of our failure.”[20]

Contrary to the Gospel of Love, the unsuccessful students grow to hate the successful ones. “Since all but the brightest children have the constant experience that others succeed at their expense, they cannot but develop an inherent tendency to hate — to hate the success of others, to hate others who are successful, and to be determined to prevent it. Along with this, naturally, goes the hope that others will fail. This hatred masquerades under the euphemistic name of ‘envy.’”[21]

Ten years later, probably a few of the students that Henry observed will remember how to reduce fractions. But surely no student will forget the real lessons learned that day, the three moral precepts of capitalism. I succeed only if someone else fails, and the converse — if someone else succeeds, I must have failed. Implicit in these two precepts is a third: My success is entirely due to me, and no other person has a legitimate claim on its benefits — the ultimate injunction of capitalism, an economic system based on individualism, where each person is solely responsible for his success or failure.

Education critic Holt contends that school, on the whole, destroys the “love of learning in children, which is so strong when they are small, by encouraging and compelling them to work for petty and contemptible rewards — gold stars, or papers marked 100 and tacked to the wall, A’s on report cards, or honor rolls, or dean’s lists, or Phi Beta Kappa keys — in short, for the ignoble satisfaction of feeling that they are better than someone else.”[22]

Through competitive rewards, school teaches students that a child who fails does not have much value. No wonder, so many of us grew to hate school and still feel our heart sink at another’s success, even if it is only a stranger “garnering plankton in the Thames.” That stranger has bested us.

Despite the introduction of cooperative learning, the awarding of trophies to every member of a Little League team, and the inflation of grades, not that much has changed in American education since its critique by Henry and Holt fifty years ago. Arguably the No Child Left Behind program of the Bush administration and President Obama’s Race to the Top with their almost exclusive emphasis on testing and meeting national standards have increased competitiveness among students and between individual teachers and schools.

Grade-school students do not have an inkling that they are being prepared for the workplace, where “the isolated individual has to fight with other individuals of the same group, has to surpass them and, frequently, thrust them aside,” observes psychoanalyst Karen Horney. “The advantage of the one is frequently the disadvantage of the other.” The situation where everyone is a real or potential competitor of everyone else creates a diffuse hostile tension between individuals, as is clearly apparent among members of the same occupational group, regardless of the disguised attempts to camouflage envy and hatred by politeness. “Competitiveness, and the potential hostility that accompanies it, pervades all human relationships,” Horney concludes from her years of psychoanalytic practice.[23] Psychotherapist Rollo May agrees: “Individual competitive success is . . . the dominant goal in our culture.”[24]

Christians — laypersons and clergy — in America adhere to two opposed systems of morality. In school, on the playing field, and in the workplace, we learn to thrust others aside, to ignore the pain and humiliation we cause others as we reach for the bauble of success. As far as I know, seminarians engage in a competitive struggle to outshine others in Greek and New Testament studies. In Sunday school and in church, we hear that we are to love others and seek the good for them for their sake. The directives “success is everything” and “love one another” are not equally balanced. Love is heard Sunday mornings, and striving for success is practiced every day. The ethos of capitalism is our dominant moral system; if a person violates its precepts, he or she will sink into a second-tier life, maybe into poverty. Success is the dominant goal of our society; not love your neighbor.

At Tyson Foods, as in the rest of America, we see Christianity in service of Capitalism. Christian beliefs are welcomed, indeed encouraged, at Tyson Foods, because such beliefs never disrupt the enterprise’s smooth operation that tramples human dignity underfoot. Preachers and politicians tell us we are a Christian nation; the way we live belies that, although we are not bold enough to say we are a capitalistic nation.

Every church I know provides food and shelter for the homeless, a commendable charity that should be encouraged, although the homeless are only .17% of the population.[25] The silence from the pulpit about the low wage workers, 44% of the population, is disgraceful, although understandable, because Christianity in America has rarely challenged the ethos of capitalism. As a result, Christianity has confined itself to a smaller and smaller area of life, until now the only public expression possible is to protest against abortion and same-sex marriage. Churches have virtually no role in political or economic life. Institutions that have little or no influence on everyday living eventually disappear, as the guilds and extended family did.

Endnotes

[1] Genesis 1:27. RSV

[2] Magaly Licolli, “As Tyson Claims the Food Supply Is Breaking, Its Workers Continue to Suffer,” Civil Eats, April 30, 2020.

[3] “Tyson Foods Releases Updated Employees COVID-19 Numbers,” https://www.5newsonline.com/article/news/local/tyson-foods-releases-updated-covid-19-numbers/527-8f521c6c-1324-4f1c-b317-5d163043ea5d.

[4] John Tyson, quoted by M. Alex Johnson, “Walking the Walk, on the Assembly Line,” http://www.nbcnews.com/id/7231900/ns/us_news-faith_in_america/t/walking-walk-assembly-line/.

[5] Tyson Foods Chaplaincy Program, https://vimeo.com/430013045.

[6] Matthew 22:39. RSV

[7] Matthew 25:31-46

[8] Milton Friedman, “Is Capitalism Humane?”, a talk filmed at Cornell University in 1978. Available http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FHPI1emZFVg.

[9] Ayn Rand, The Virtue of Selfishness (New York: Signet, 1964), p. ix.

[10] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Harper & Row, 1966 [1835,1840]), pp. 527-528.

[11] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, the Second part of the Second Part, Question 66, Article 7.

[12] Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman, “Meet the Low-Wage Work Force,” https://www.brookings.edu/research/meet-the-low-wage-workforce/.

Jane Mayer reports that the working conditions at Mountaire Farms, the seventh-largest producer of chicken in the United States, are worse than at Tyson Foods. See Jane Mayer, “How Trump Is Helping Tycoons Exploit the Pandemic,” The New Yorker (July 13, 2020).

[13] Anna Stansbury and Lawrence H. Summers, “The Declining Worker Power Hypothesis: An Explanation for the Recent Evolution of the American Economy,” https://www.nber.org/papers/w27193.

[14] Data from “For Most U.S. Workers, Real Wages Have Barely Budged In Decades,” Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/.

[15] Daron Acemoglu, quoted by Thomas B. Edsall, “Why Do We Pay So Many People So Little Money?” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/opinion/wages-coronavirus.html?action=click&module=Opinion&pgtype=Homepage.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Mark 12:13-17. RSV

[18] Psalm 24.1 NIRV

[19] “World’s 26 Richest People Own as Much as Poorest 50%, Says Oxfam,” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jan/21/world-26-richest-people-own-as-much-as-poorest-50-per-cent-oxfam-report.

[20] Jules Henry, Culture Against Man (New York: Random House, 1963), pp. 295-296.

[21] Ibid.

[22] John Holt, How Children Fail, rev. ed. (Reading, MA.: Perseus, 1982), p. 274.

[23] Karen Horney, The Neurotic Personality of Our Time (New York: Norton, 1937), p. 284.

[24] Rollo May, The Meaning of Anxiety, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 1977), p. 173.

[25] State of Homelessness: 2020 Edition, https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-2020/.