|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

I had thought myself lost, had touched the very bottom of despair; and then, when the spirit of renunciation had filled me, I had known peace. . . . In such an hour, a man feels he has finally found himself. St. Exupéry, Wind, Sand, and Stars

In America, belief is all over the map. Christians believe in a good, loving God, a providential caregiver for each of them; Buddhists, through meditation, strive for compassion for all beings; atheists hope that freeing themselves from all religious nonsense will make them happy. What Christians, Buddhists, and atheists have in common is the core assumption that nature and society are predictable, so each of them can direct their lives to the good end they have chosen. Everyone believes they can control their lives because nature and society are governed by necessity, not chance, a belief the Covid-19 pandemic shattered.

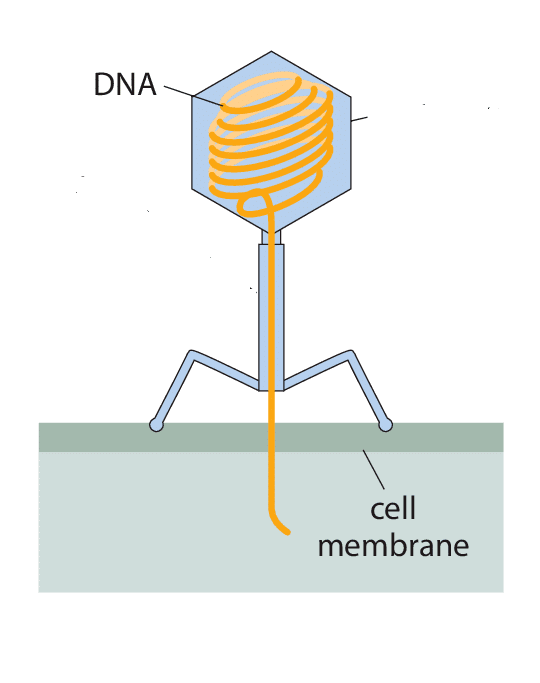

The Covid-19 virus is a macromolecule, about a hundredth the size of an average human cell; its RNA  core is surrounded by a protein coat called the capsid, which in turn is surrounded by a spikey coat called the envelope. (In the illustration, the spikey coat is not shown.) The Covid-19 virus, like all viruses, has no cell membrane to receive materials selectively from without, no way to assimilate food, and no way to produce energy — all functions of the simplest cell. Because they have no metabolism, viruses cannot replicate themselves outside of a living cell. To replicate itself, a virus, or at least its nucleic acid, must be injected into the cell whose materials and energy sources the foreign nucleic acid commandeers to produce identical copies of itself. And, unlike reproduction in plants and animals, replication in viruses requires the disintegration of the “parent” virus.

core is surrounded by a protein coat called the capsid, which in turn is surrounded by a spikey coat called the envelope. (In the illustration, the spikey coat is not shown.) The Covid-19 virus, like all viruses, has no cell membrane to receive materials selectively from without, no way to assimilate food, and no way to produce energy — all functions of the simplest cell. Because they have no metabolism, viruses cannot replicate themselves outside of a living cell. To replicate itself, a virus, or at least its nucleic acid, must be injected into the cell whose materials and energy sources the foreign nucleic acid commandeers to produce identical copies of itself. And, unlike reproduction in plants and animals, replication in viruses requires the disintegration of the “parent” virus.

New viruses result from old viruses through two chance processes, copying errors on replication and horizontal gene transfer from another virus. Although these mechanisms are understood, what new viruses will emerge in the future is not predictable.

Viruses are dead, lifeless macromolecules.

Right now, the human species is threatened by a tiny, dead piece of matter that arose by chance, yet is governed by necessity — the genetic code and its transcription into proteins.

Society is also governed by chance and necessity. Four years before the near worldwide economic depression of 2008, Ben Bernanke, later the Chair of the Federal Reserve, proudly announced the Great Moderation: “One of the most striking features of the economic landscape over the past twenty years or so has been a substantial decline in macroeconomic volatility.” Bernanke attributed the Great Moderation to “improved monetary policy,” that is, to a deeper understanding of the economy that led to greater control of the machinery of buying and selling.[1] 2008 taught some of us that the Great Recession was caused by ignorance, that economists did not truly grasp the complexities of advanced economies, that despite their mathematically sophisticated analyses and well-meaning policies they did not know how to avoid the collapses intrinsic to capitalism. The Great Recession briefly shook the hubris of economists: Paul Krugman, winner of the 2008 Nobel Memorial prize in Economic Science, confessed his “profession’s blindness to the very possibility of catastrophic failure in the market economy;”[2] less than ten years later, the overarching pride of his profession returned, as expected. We humans, not just economists, believe we can control all aspects of our lives; when an expected event hammers us to the ground, we get up, innovate, and stagger on, soon forgetting that the future is not predictable.

Determinism

Economists hoped, and probably still do, to make their science predictive like Newtonian physics. Psychologist Joshua Greene and neurobiologist Jonathan Cohen give an excellent statement of the determinism adhered to by most scientists. “Intuitively, the idea is that a deterministic universe starts however it starts and then ticks along like clockwork from there. Given a set of prior conditions in the universe and a set of physical laws that completely govern the way the universe evolves, there is only one way that things can actually proceed.”[3] In this picture, the current state of the world is completely determined by the laws of physics and by any one of its past states.

Greene and Cohen rightly point out that in the Newtonian Cosmos every event apart from the Big Bang results from prior mechanical causes. That I would appear in the universe with a small mole on my right temple was in the cards one second after the Big Bang. Two years ago, a long chain of mechanical caused my wife to buy a new Marimekko dress. The precise attunement of particles in the early universe led Francis Crick and James Watson to discover the structure of DNA, Charles Townes to conceive the laser, da Vinci to paint the Mona Lisa, and Mozart to compose the Requiem Mass in D Minor. The deterministic outlook that permeates all science necessarily proclaims that human beings possess no free will, that we are machines, mere pawns moved about by mindlessly forces in a mechanical universe governed by the laws of necessity.

Even the great Albert Einstein was a determinist. “I am a determinist,” he proclaimed. “As such, I do not believe in free will. The Jews believe in free will. They believe that man shapes his own life. I reject that doctrine philosophically. In that respect, I am not a Jew.”[4]

The determinism that is a central aspect of the Newtonian Cosmos is false, for two reasons — quantum physics and chaos theory. In the twentieth century, physicists discovered individual events on the atomic level are not predictable. Consider uranium 238, a commonly occurring radioactive substance. A gram of uranium 238 contains approximately 2.5×1021 identical uranium nuclei; about 12,000 of those uranium nuclei decay every second into an alpha particle and a thorium 234 nucleus. Quantum physics can predict the probability that a given uranium 238 nucleus will decay but not when it will. The exact moment of decay is intrinsically unknowable because such decays are governed by chance, not the laws of necessity. Unpredictability thus is an integral part of nature.

On the macroscopic scale, chaos theory killed determinism. The basic element of chaos theory first appeared in the astronomical investigations of French mathematician Henri Poincaré at the end of the nineteenth century, but only in the latter part of the twentieth century with the advent of computers did physicists and mathematicians see the full significance of his work. While investigating a system of three gravitating bodies, such as the Earth, Moon, and Sun, the so-called “three-body problem,” Poincaré discovered that unpredictable behavior occurs in deterministic systems, a fact that has startling implications for the mathematical modeling of physical systems. Before his revolutionary work, physicists and mathematicians assumed that small errors in the initial conditions of any dynamical system produced only small errors in the mathematical prediction of the future state of the system. Poincaré’s analysis of the three-body problem is brilliant and highly technical; yet, the basic result can be easily stated, as Poincaré himself did in his popular book Science and Method: “It may happen that small differences in the initial conditions [of a mechanical system] produce very great ones in the final phenomena. A small error in the former will produce an enormous error in the latter. Prediction becomes impossible, and we have the fortuitous phenomenon.”[5]

Meteorologist Edward Lorenz called what Poincaré discovered fifty years before his work the “butterfly effect,” where a flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil could set off a tornado in Texas. Because of the impossibility of measuring initial atmospheric conditions precisely, the weather cannot be predicted accurately more than a week or so in advance. Vladimir I. Arnol’d, a Russian mathematician, proved, in 1963, that depending upon the initial conditions, the motion of three gravitating bodies can be either predictable or chaotic. Advances in computer technology have made it possible to begin to directly address the long-term evolution of the solar system. The results of Gerald Jay Sussman and Jack Wisdom suggest that the solar system as a whole is chaotic, making its long-term behavior uncomputable.[6] In particular, their computer models indicate that the Pluto has a chaotic orbit and that astronomers cannot predict whether the planet will be on this side of the Sun (relative to the Earth’s position) or on the other side ten million years from now.[7]

The clockwork cosmos is an intellectual error of the Dark Ages of Science; we must quell our desire for absolute certainty; we live in a world of chance and necessity.

Our Strange Relationship with Chance

Whenever we are in Charlottesville, Virginia visiting my older daughter, my wife and I after dinner play Hearts with our two grandsons. Without chance, no one would be surprised when they picked up the cards dealt them; no one would deliberate about which card to play on a given trick; the game would be of no interest. Without necessity that fixes the thirteen cards in four suits, the game would be chaotic and not playable. Chance makes Hearts exciting; necessity makes it possible.

A balance between chance and necessity, usually exquisite, makes life interesting and sometimes amusing. Out of biological necessity, each one of us is born into a distinctive family and a particular culture that give us a certain direction in life, furnish us with personal problems to solve or demons to overcome, and stuff ideas into our heads that are often opposed to reality.

I, for instance, was born in America and could not base my beliefs on tradition, custom, or class. My constant reference point, then, was always myself. As a result, I formed the habit of thinking of myself in isolation from other persons, and this habit carried over when I thought about things. In this way, I acquired the culturally-given habit of thinking: To understand something, isolate it, so it exists apart from all relations.[8]

Hence, I believed that every part can be separated from the whole and that the whole can be understood as merely a collection of parts. With such a habit of mind, I attempted to understand every whole solely in terms of its parts. But the smallest parts of anything are material. Therefore, the culturally-given habit of thinking the whole is a collection of parts made me a firm believer in materialism — at that time, I could not think any other way.

As if led by the hand of a trusted adult, I ended up at Los Alamos National Laboratory on a post-doc in theoretical physics. Science in league with democracy and capitalism instructed me that only matter exists. Capitalism set me on the path to consuming more and more, so I would be happier and happier, and not to pay attention to the losers in the economic game or to question the source of my wealth, the Laboratory for the Destruction of Humankind. American democracy, in concert with science and capitalism, told me I was an isolated, autonomous individual, a disastrous belief I clung to for too many years.

For me, a committed materialist and thoroughgoing nihilist at the time, I could not come up with a rational argument why I should not continue to be a new barbarian at Los Alamos National Laboratory and live high on the hog, drinking Chateaux-bottled wines and smoking cigars smuggled in from Havana. I had no allegiance to the new god, the Nation-State, nor did I accept what American culture repeatedly tried to pound into my head — natural self-interest drives a person to acquire more and more. As a result, I did not have a moral system, map, philosophy, or worldview that could reliably direct me to choose one course of action over another. And then came chance.

Hiroshima changed everything for me; I wanted no part in working for the destruction of humanity. For the first time in my life, I grasped that my life was not mine alone, that what I choose to do would affect others, and that I was inextricably bound to others, even to all humanity. In the course of my crazy, zigzag life, I arrived at the place where John Donne had been four hundred years before me. “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. . . . any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”[9] And, I heard the bell toll for me.

My post-doc ended, and the Laboratory for the Destruction of Humanity offered me a lucrative position in the Theoretical Physics Division, with the proviso that I work quarter-time analyzing data from the Nevada Test Site. I walked away, bid the Laboratory adios, even though my gypsy heart said take the money and pretend to live a comfortable, middle-class life — three years in the heart of darkness was enough for me.

For the first time in my life, I made a genuinely moral decision, one that would cost me many dollars, one that would earn me the ridicule of my former colleagues, and one that would end my career as a physicist. If necessity governed the cosmos, I would have been a pawn of matter, moved about by mindless forces, incapable of transcending my cultural formation. Chance broke necessity and made moral choice possible.[10] When I was in Los Alamos, chance was my friend.

Overwhelmed by Chance

Chance can be our enemy. That my older daughter got breast cancer in her mid-forties was pure chance. That I have Hashimoto’s disease and passed it on to my son is chance operating twice in succession.

No one foresaw in August 2019 that on 17 November 2019 that the first case of Covid-19 infection would occur in Wuhan, China and that a pandemic would ensue. In December 2019, I bought airline tickets to Charlottesville, which I canceled in February 2020 and conceded the purchase price to Delta. My younger daughter signed a book contract in May 2019, but who knows the fate of A Good and Hard Place: Exploring the Trouble of America in Small Town Vermont in 2020. My son bought a $250,000 canning line for his brewery in October 2019, a purchase that almost cut him off at the knees in March 2020.

Millions of our fellow citizens have fared worse than we have. Far more people are suffering from economic woes than from the devastating grief for a lost relative or friend. In the last four weeks, 22 million new unemployment claims were filed. Like Covid-19, the economic disaster does not recognize gender, race, or ethnicity. A Black man, homeless for two years, said, “Things were looking up when everything drastically changed with the pandemic;” his housekeeping job at Caesar’s Entertainment terminated two days before he was scheduled to begin. A violinist with the National Symphony was furloughed, a new experience for her; she asked, “Why am I suddenly afraid of the mail carrier and the food delivery guy?” An owner of an upscale boutique, shuttered by the social distancing mandate, lamented she wanted to keep paying her twelve-woman team but couldn’t. A filmmaker worried that in a month, he would have zero funds; he had always paid his bills on time; his anxiety about the future was crippling. A young salesclerk missed the routine of her job, and said, “You go from feeling secure to how am I going to make next month’s rent.” A college senior returned home after his university closed. His career hopes thwarted, he fell into deep a depression: “I’m stuck in my parents’ house, and I spend days alone crying.”

The pain and suffering have just begun. The shipping abroad of Midwestern manufacturing jobs, the closing of the steel mills in Pennsylvania, and the shutting of the coal mines in West Virginia resulted in “deaths of despair” caused by drug addiction, alcoholism, and suicide.[11] In America, employment is not just a job, but a daily routine, friends, and a purpose. Strip all that away, and a worker within three months experiences boredom, hopelessness, and depression; she may self-medicate with Pinot Noir or OxyContin.[12]

Consider the woman (Lauren Martin) mentioned above, who owns a high-end boutique. Here is the worst-case scenario for her. The low to zero interest loans for small businesses, one of the federal 2$ trillion bailouts, became ensnared in bureaucratic nonsense and the refusal of big banks to underwrite such loans, just as in the Great Recession of 2008. As a result, Lauren’s business is finished. She rapidly depletes her personal savings; she had invested heavily in her business because she did not want to be beholden to banks and outside investors. Those are the possible economic hardships that pale in comparison to the potential emotional pain.

Lauren was proud of herself as a successful woman entrepreneur. She supported her aging mother in a nursing home, and, on and off, bailed out her brother, who couldn’t get his life straightened out. Her twelve-woman team respected her; some worshipped her; that love and friendship were gone forever. A chance event, the Covid-19 pandemic, locked Lauren in her apartment, stripped her of worth and dignity, the loving arms of friends, and the comfort of her church. Hopeless, the bottle of Triazolam was at hand.

But a different ending of this terrible scenario is possible. Lauren had regularly practiced meditation to relieve anxiety and cool anger. She found that when a difficult problem with an employee of the boutique arose, if she meditated fifteen minutes before meeting with her, the problem somehow quickly resolved itself.

Confined to her apartment by the social distancing mandate, Lauren meditates to still her monkey mind, jumping from one worry to another. She hears as if for the first time the words of her guru: “Unlike the Buddhism of the Pāli canon and the Theravāda tradition, contemporary Buddhism, particularly in America, understands the Path as psychological development. Meditation helps us cope with personal problems, especially our monkey minds and our afflicted emotions. In contrast to Asian Buddhism that aims to leave the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, our pre-occupation is mainly therapeutic.”

Without thinking, Lauren shouted, “Bullshit!”

The Covid-19 pandemic stripped away everything Lauren had taken herself to be. She was nothing and teetered on the edge of the void, the vast sea of nothingness. And then she began to laugh; she suddenly realized that “Lauren Martin” is an illusion, frail and fleeting, with no more permanency than a smoke ring, doomed to disappear into nothingness with the death of her body. The fear was gone, and the laughter brought about inner freedom.

In a roundabout way, Lauren arrived at the central insight of the Buddha — the self is an illusion. In the Deer Park at Isiptana, the Buddha preached his second sermon, The Discourse on Not-Self, and “while this discourse was being spoken, the minds of the monks of the group of five were liberated from the taints by nonclinging.”[13] Arguably, anattā, a Pāli word that means no-self, is the most important and most challenging concept in Buddhism, since it led the five monks to instant enlightenment, to Nirvāṇa, to “the annihilation of the illusion [of self], of the false idea of self.”[14]

The best-case scenario for Lauren Martin can be written in terms of Christianity. One Sunday morning, no longer able to attend services at her church, Lauren sits on her couch with a pious look on her face and with folded hands in her lap. She recalls one of Pastor Kathy’s comforting sermons. “Maybe the next life will be a feast for the mind, like great expanses of time in the main reading room in the Library of Congress, only with good lighting and comfortable chairs. Maybe it will be bountiful, like the homecoming picnics at the Martin City Methodist Church, where my father worshiped as a boy. Sometimes I play with the idea that I will see my grandfather, whom I loved deeply and who died when I was nine, and meet my German grandparents for the first time. Maybe I can have a beer with Meister Eckhart or crochet and chat with Dame Julian of Norwich, while she sews on humble garments, suitable for anchorites. Maybe, I will play with my favorite dog, Sparky.”

When Lauren hears “Sparky,” she begins to laugh and laugh; tears run down her cheeks. She laughs so loud she cannot articulate what she wants to say. “What . . .” Uncontrollable laughter, tears wiped away by both hands. Then the words come out. “What bullshit!” Lauren was now fearless; she had seen the Light.

The disruption and pain caused by the Covid-19 pandemic forced Lauren to see that she is not her memories, not an American, not even an Episcopalian. She was not the humiliated seventh grader embarrassed by her hand-me-down clothes, desperately wanting to belong, to have a friend. She was no longer lost in her ego or mistook the transient for the eternal, the cultural for the divine, written words for the Word. By falling into nothingness, Lauren discovered the central insight of the mystical theology of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopogite: “God is not any of the names used in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, not God of gods, Holy of holies, Cause of the ages, the still breeze, cloud, and rock.”[15] God is not Mind, Greatness, Power, or Truth in any way we can understand, for He “cannot be understood, words cannot contain him, and no name can hold him. He is not one of the things that are, and he is no thing among things.”[16] God is the Unnamable.[17]

Lauren Martin is nameable but being an image of God is unnamable; her true self, the one created by God, is unnamable. Until the chance, disastrous Covid-19 pandemic stripped away her culturally-given self, her true self was hidden, and she thought she was what she had witnessed. She, too, cannot be contained and is not a thing among things. The Light had freed her from the fear of death and given her unbounded freedom.

Endnotes

[1] Ben Bernanke, “The Great Moderation,” (Feb. 20, 2004), https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2004/20040220/.

[2] Paul Krugman, “How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?” New York Times (Sept. 2, 2009), https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html.

[3] Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen, “For the law, neuroscience changes nothing and everything,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London B (2004) 359: 1781. Available http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~jgreene/GreeneWJH/GreeneCohenPhilTrans-04.pdf.

[4] Albert Einstein, quoted by Walter Isaacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007), p. 387.

[5] Henri Poincaré, Science and Method, trans. Francis Maitland (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2003), p. 68.

[6] See Ivars Peterson, Newton’s Clock: Chaos in the Solar System (New York: W.H. Freeman, 1993), Ch. 11.

[7] Gerald Jay Sussman and Jack Wisdom, “Numerical Evidence that the Motion of Pluto Is Chaotic,” Science 241 (1988): 433-437.

[8] For a detailed discussion of the modern habits of thinking, see George Stanciu, “The Fetters of ‘Free Thought’”, https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2017/03/fetters-free-thought-george-stanciu.html.

[9] John Donne, Essays, Meditation XVII. Available http://www.online-literature.com/donne/409/.

[10] The deeper reason we can choose is the map is not the territory. We humans are mere mortals, incapable of understanding the totality of being, although virtually no physicist, neuroscientist, biologist — or philosopher or political thinker or theologian, for that matter — can resist the temptation to be God, to claim he or she captured the whole show in three equations or in one intellectual insight or in a clever political slogan.

We should always keep in mind that every map is limited. For Instance, John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government is a map of political life, one that gave direction to the Founding Fathers of America; Locke’s map does not include anything about philia (friendship) and agápē (Christian love), which bound together the Greek polis and the medieval village, respectively.

For a detailed discussion of the map is not the territory, see George Stanciu, Determinism: Science Commits Suicide.

[11] See Anne Case and Angus Deaton, “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century,” https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/casetextsp17bpea.pdf.

[12] Students of Plato’s Republic know from an extended reading of the book that like every human being, we Americans were born in a Cave and that the first step to the transcendent is to unmask the opinions and beliefs that have been stuffed into our heads, the “truths” of democracy and capitalism. The Covid-19 pandemic is doing that in a brutal manner for most of us, although just as in the Republic, we resist in any way we can.

[13] Anatta-lakkhana Sutta: The Discourse on the Not-self in In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pāli Canon, trans. Bhikkhu Bodhi (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2005), p. 342.

[14] Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught, (New York: Grove Press, 1974), p. 37.

[15] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Divine Names in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 596A.

[16] Ibid., 872A.

[17] The map is not the territory! Aquinas’ Summa Theologica is a map, one that many believers take for the territory. However, shortly before his death, Aquinas had a mystical experience when celebrating the Mass, and as a result, he left his masterpiece unfinished. When urged by Reginald of Peperino to explain the radical change in his religious perspective, Thomas simply said, “Everything I have written seems like straw by comparison to what I have seen and now what has been revealed to me.” No map can contain God, or us, for that matter. C