|

Audio: Listen to this post.

|

The Patristic Fathers embraced the theological insights of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopogite[1]: God is not any of the names used in the Old and New Testaments, not God of gods, Holy of holies, Cause of the ages, the still breeze, cloud, and rock.[2] Pseudo-Dionysius insists that God is not Mind, Greatness, Power, or Truth in any way we can understand. God “cannot be understood, words cannot contain him, and no name can hold him. He is not one of the things that are, and he is no thing among things.”[3] God is the Unnamable.

The image of God within us means, then, that each one of us is unnamable and known to others through our activities in the world, that is, through a socially-constructed self. We are unknowable to ourselves, although through meditation—what the Patristic Fathers called contemplation—we can witness our thoughts, memories, and storytelling, and thus know that we are not what we witness. Through more advanced contemplation, we may experience Divine Light, the presence of God.

At the core of our being is the unnamable, the “empty mind” of Zen Buddhism, the “pure consciousness” of Hinduism, and the “spirit” of Christianity, although all words ultimately fail to capture our true self. We, the unenlightened, believe that the false self given to us by culture is permanent and survives death. Because we take our culturally-given self for our true self, we fail to experience who we truly are. Our true self is always present, perfect, with no need for our development; we must merely step aside. Every spiritual master calls for the death of self and a spiritual rebirth beyond egoistic desires, beyond religious practices, beyond any given culture, beyond the laws of society, into the law of love, into compassion for every living being.

The image of God within us also means that each one of us has the energy to transform the physical and social worlds we inhabit, either for good or evil. For instance, we are free to use the fruits of science for the benefit of life or the destruction of humanity, for creating polio vaccine or thermonuclear weapons, aids for life or instruments of death. Through such free choices, we either draw closer to God or more distant from Him.[4] Each one of us becomes what we choose.

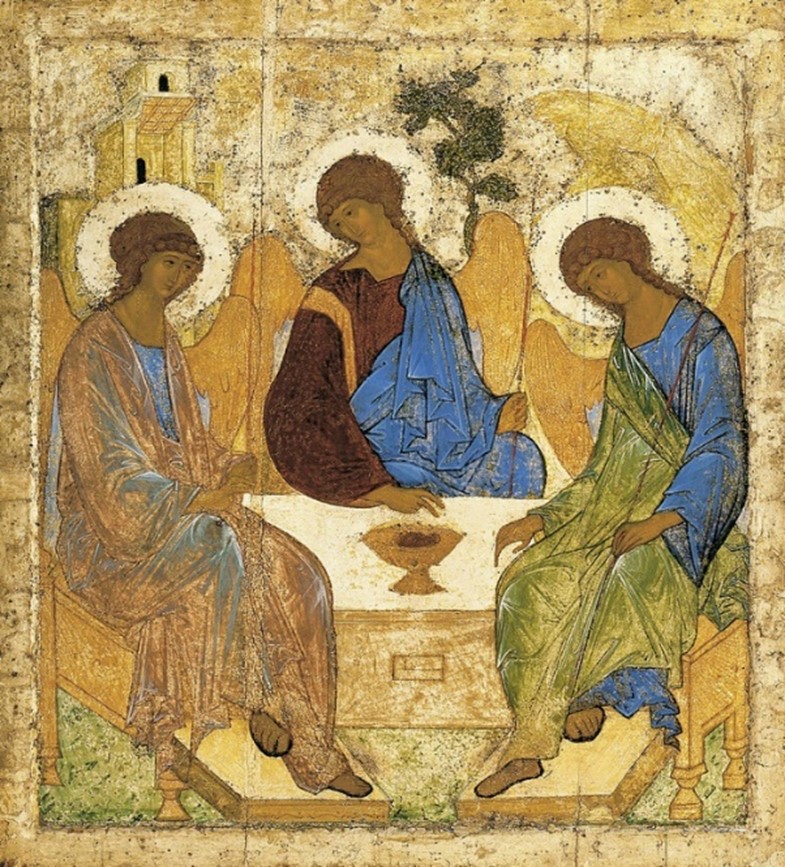

Our freedom is virtually unlimited; we can thumb our noses at God, refuse to become who we truly are, and embrace a self of our own choosing. However, to freely abandon God, to exist in oneself, and to seek satisfaction in one’s own being is not quite to become a nonentity but is to verge on non-being.[5] Hell is not the fiery pit of received Christianity, but the complete separation from God—forever. Heaven is not the reuniting with one’s favorite dog, the blissful meeting with one’s unknown relatives, or the pleasure of conversing with the saints, not such “enthusiastic fantasies,” but to “know more deeply the hidden presence by whose gift we truly live.”[6] The Trinity also called The Hospitality of Abraham by Andrei Rublev appears to suggest that heaven is joining the Holy Trinity in the afterlife. (See figure.)

We moderns tend to view icons as primitive art that lacks the techniques of perspective discovered by Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo said, “Painting is based upon perspective which is nothing else but a thorough knowledge of the function of the eye.”[7]

By careful examination of vision, Leonardo discovered that the colors of nearby objects are brighter and sharper than remote objects. To render this insight into a painting, Leonardo invented sfumato, Italian for “smokiness,” the technique of shading an object with transparent layers of oil paint to create smoky shadows, as readily seen in his painting Virgin of the Rocks. Mary has her right arm around the infant St. John the Baptist, who is making a gesture of prayer to the Christ child, who in turn blesses him. Mary’s left-hand hovers protectively over the son’s head while an angel looks out and points to St. John. The figures are all in a mystical landscape with rivers that seem to lead nowhere and bizarre rock formations. In the foreground, we see precisely rendered plants and flowers. (See figure.)

The printing press with moveable type was invented by Johannes Gutenberg around 1436, so the first viewers of The Virgin of the Rocks were mainly illiterates who heard the New Testament read aloud in church and sermons about how Mary and Elizabeth, the mothers of Jesus and John the Baptist, fled with their sons into Egypt. The Virgin of the Rocks illustrates the first meeting of the infants Jesus and John the Baptist in a protected rocky grotto where, amid their flight, they have paused to rest. Da Vinci illustrates a story familiar to believers so they seem to be present at a biblical event; such presence strengthens their faith.

Out of habit, we view icons as visual representations of biblical narratives. Given this prejudice, we understand Rublev’s The Holy Trinity as a visual representation of a story from Genesis 18:1-15 called “Abraham and Sarah’s Hospitality.” The biblical narrative begins when “the Lord appeared to [the biblical Patriarch Abraham] by the oaks of Mamre, as he sat at the door of his tent in the heat of the day.” The three men standing in front of him were angels. When he saw them, he ran from the tent door to meet them and bowed himself to the earth,and said, “My lord, if I have found favor in your sight, do not pass by your servant.” Abraham ordered a servant-boy to prepare a choice calf, and set curds, milk, and the calf before them. He stood by them under a tree as they ate. One of the angels told Abraham that Sarah would soon give birth to a son. Hiding in the tent, Sarah laughed, for she was old, far beyond childbearing. The angel heard her laugh and said, “Is anything too hardfor the Lord?”

Later, Christians understood the three angels as the three persons of the Holy Trinity. In The Hospitality of Abraham, the angel to the far left represents God the Father. The angel’s robe is highlighted with brown, blue, and green colors to show the impossibility of rendering God the Father as one image. The angel to the far right wearing pale green and blue represents God the Holy Spirit. In iconology, green is associated with the Spirit’s “youth, [and] fullness of powers,[8] and blue symbolizes the everlasting world, the Kingdom of God. The figure of God the Son, the central angel, portrays Christ as Priest, Prophet, and King. Christ holds his hand over the cup of sacrifice; his fingers are bent in the Orthodox sign of blessing and with a bowed head as if saying, “My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me. Yet not as I will, but as you will.”

The Oak of Mamre symbolizes the tree of life and reminds the viewer of Jesus’s death on the cross and his subsequent resurrection, which opened the way to eternal life. The Oak is in the center of the icon above the angel, who represents Jesus. Abraham’s house appears above the angel’s head on the far left. The hint of a mountain on the far right denotes spiritual ascent, which mankind accomplishes with the help of the Holy Spirit.

While all the above is true and helps a devoted believer to reflect on the Trinity and strengthen his prayer life, the most important feature of the icon is the inverted perspective. The angels in the icon are arranged so that the lines of their bodies form a circle. In motionless contemplation, each angel gazes into eternity. Because of the inverted perspective, the focal point of the icon is in front of the painting on the viewer; Rublev is inviting the viewer to engage in an amazing spiritual exercise, to complete the circle of angels, to join in a union with the Holy Trinity, to become a “partaker of divine nature.”[9] A possibility because in Christ, a Divine Person, the human and the divine are joined together in a perfect and indissoluble unity. In Christ, God Himself descended into our midst, so we “may have life, and have it abundantly.” Every person could become a “partaker of divine nature,”[10] because, in Christ, a Divine Person, the human and the divine are joined together in a perfect and indissoluble unity. In Christ, God Himself descended into our midst, so we “may have life, and have it abundantly.”[11] Many Church Fathers were fond of telling their brethren, “God became man, so man might become God.” Made in the image of God means a divine element inheres in every human person, in Jew and Greek, in master and slave, in male and female.

As we repeatedly view the icon and attempt to join the Holy Trinity in contemplation, the trivial, mundane aspects of who we are begins to fade. Some experience that our false self, necessary to serve others, is of no consequence. In freedom, we walk the world serving others.

Endnotes

[1] Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite is the anonymous theologian of the late 5th to early 6th century whose works were erroneously ascribed to Dionysius the Areopagite, the Athenian convert of St. Paul mentioned in Acts 17:34.

[2] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Divine Names in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 596A.

[3] Ibid., 872A.

[4] See Gregory Palamas, Topics of Natural and Theological Science and on the Moral and Ascetic Life: One Hundred and Fifty Texts in The Philokalia, Vol. IV, ed. and trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1984), p. 382.

[5] See Augustine, City of God, Bk. 14, Ch. 13.

[6] Joseph Ratzinger, Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, 2nd ed., trans. Michael Waldstein (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1988), pp. 233-234.

[7] Martin Kemp ed., Leonardo on painting: An Anthology of Writings by Leonardo da Vinci with a Selection of Documents Relating to His Career as an Artist, trans. Martin Kemp and Margaret Walker (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), p. 22.

[8] Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, The Meaning of Icons, trans. G. E. H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovski (New York, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1999), p. 202.

[9] 2 Peter 1:4. RSV

[10] 2 Peter 1:4.

[11] John 10:10.

2 Responses

Thanks Professor, I especially appreciate the analysis of the paintings. Including the audio is also a neat touch. Blessings, <

Thanks. George